Confessions of an Augustinian Quaker

If St. Augustine were to travel through some cosmic wormhole from the late Roman Empire to our time, to our age of televangelists and post-Christian gurus, I bet he’d remark that the Manichees had triumphed. The ancient sect of Mani, which Augustine joined in his youth and later opposed, had a message similar to today’s mass-media sects: one centered on a simplistic cosmic struggle between good and evil, angels and demons, the enlightened few and the unenlightened masses, the saved and the lost—nuance be damned. In their ancient and (post)modern guises, Manicheans have capitalized on the human desire to possess a special knowledge, and to be sure of it beyond a reasonable doubt—hence the hunger for mysteries solved, for utopias, for esoteric language and rituals.

But for true seekers, like the young Augustine, a sect like this was bound in the end to disappoint. Underneath the polished veneer, these sects have always had little time (or patience) for earnest questions. Like the sect of Mani and its bishop Faustus (mentioned in Book V of Augustine’s Confessions) their rhetoric lacks depth or substance.

It is compulsive dissent of the restless heart, striking like a stubborn chisel, that leads to God over the long haul, if not always in the short term. Or such is Augustine’s classic proposal: Fecisti nos ad Te, Domine, et inquietum es cor nostrum donec requiescat in Te. (“Thou hast made us for thyself, O Lord, and our heart is restless until it finds its rest in thee.”)

It’s common to refer to spiritual journeys (with good reason) as pilgrimages. The metaphor is a fitting one. It helps me, among other things, to describe the detour I took from the Christian path during those college and post-college years—as well as what got me back on it. As those who have hiked (or biked) pilgrimage routes like the Camino de Santiago know, detours can happen for a host of reasons: injuries, chronic discomforts, stretches too steep or strewn with obstacles, or stretches that are just not suited to bicycles (as my wife and I can attest after our own venture). But, as caminantes can also attest, detours need not be permanent. The ubiquitous blue-and-yellow signposts—bursting like sunflowers beside the cobblestone, the windmills, and the vineyards—are to be found not just on the trail itself but in all sorts of neighboring areas, pointing one back.

So what set me off on a detour? What caused me to end up such a doubting Thomas after such an auspicious start? What caused me to join the Peace Corps instead of Operation Mobilization (OM, the evangelistic organization I was raised in)? Well for one thing, these were the 1980s. There was the discomfort a lot of us felt with the nascent Religious Right, which was equating the will of God with the interests of the USA and spicing it up with esoteric Bible prophecies. The Cold War was still in full swing, and its narrative that pitted us against the “evil empire” of godless Communism had quite a grip on the popular imagination. This political Manicheism was one thing that made the Christian path (or at least this evangelical stretch of it) so unsuitable. Having grown up in Latin America, I was all too aware that the USA was backing murderous regimes: dictators who happened to be anti-Communist but who were no less brutal than today’s drug cartels. I knew things weren’t that simple.

There was also that stark division (one that predated the 1980s, to be sure) between the sacred and the secular—between “spiritual things” and things belonging to a corrupt material “world.” The subculture of Christian books, music, and education felt like a withdrawal into a narrow (sometimes austere and sometimes gilded) fortress, which induced cultural claustrophobia, like a pair of hiking shoes one size too small, or a bike stuck in one gear. And to top it off, there were all those shenanigans of the 1980’s prosperity-gospel preachers (now parodied in the TV series The Righteous Gemstones), part of a wild zig-zag between self-denial and self-indulgence (which, as it happens, was a feature of Manichean forms of religion going back to the late Roman Empire).

But most troubling of all was the simple division of the whole human race into the categories of the “saved” destined for heaven (and the imminent “rapture”) and the “unsaved” destined for hell (following the dystopian nightmare of the coming Antichrist). This particular dualism, in addition to the immense discomfort it caused me, was never going to withstand the encounter (more and more common in college) with the virtuous non-Christians—even the virtuous atheists. There was no satisfying answer, for me, to the question “What kind of God would condemn virtuous non-Christians, like the ones I knew?”

I’ve often wondered about that religious crisis of faith that began my sophomore year of college, and whether it could have been avoided. I wonder if I could have arrived at the place I’m at now through a process of organic evolution instead of sudden rupture. Could I have just stayed on the trail and found, over time, a later stretch or branch of it, one more congenial? I’ll never know. But the detour was never definitive. There were ubiquitous signposts pointing me back to the trail, like those yellow-on-blue arrows and conch shells that point one along or to the Camino. There were those forces that kept tugging, like some gravitational pull, preventing me from careening too far into outer space.

It’s possible that I inherited from my late mother a predilection for mystical experiences. Hers (which she describes in her own memoir) were much more elaborate than mine—and she would have used other words or phrases (like “messages from God” or “spiritual visions”) to describe them. Regardless, I had one fleeting but vivid experience that bears mentioning. It happened during an “all-night prayer meeting” during the time when I was still active in OM, and featured an image of what I can best describe as translucent, emerald beings gathered around a central figure that I understood to be Christ—even though he looked nothing like the familiar images from religious art. (One Bible scholar friend, when I later described this to him, pointed out, wide-eyed, its striking resemblance to the visions of St. John in Revelation 4 and 5 and the visions of the prophets Daniel and Isaiah.) But unlike the prophets of old, I make no grand claims for this experience, and received no message that I could articulate. All I can claim is its personal effect, which was like the implantation of a spiritual magnetic force.

Echoes of this experience would come back to me for years after that, like a recurring dream. Its presence, even during my most agnostic moments, would always happen in connection with certain types of sacred music I still listened to on occasion: Celtic hymns, or the a cappella harmonies of Taize or Ladysmith Black Mambazo (who happened to arrive on the world stage while I was serving as a Peace Corps volunteer in Africa). What struck me about these moments was the fact that I could never reduce them to a familiar aesthetic emotion, or to synesthesia (the experience in which sounds evoke colors, and harmonies become visible). It was these things of course, but also much more: a sensation of enormous height and depth that made the purely secular (post)-modern road I was on feel flat and two-dimensional by comparison. This was the restlessness of St. Augustine, now pulling me back in the other direction.

There are other terms besides mystical experience to name this cluster of experiences. C. S. Lewis might have recognized in them the experience of joy—that longing for a transcendent heaven that came to him through Norse myths and certain children’s books. And the British theologian John Milbank (whose project is called postmodern critical Augustinianism) might have pointed out that the spiritual “flatness” that I was sensing comes indeed from the “flattening” of our (Western) culture that started as far back as the late Middle Ages, necessitating a renewed attention to St. Augustine, some of his ancient Greek sources, and some of his mystical heirs (like Meister Eckhart and Soren Kierkegaard).

I attend Quaker meetings now, but my theological mentors read like a Who’s Who of British Anglicanism. In addition to C. S. Lewis and John Milbank, I’d need to cite John Stott and N. T. Wright, among others. One common denominator I find among these Anglican writers is their focus on the ancient sources of the Christian faith (which happen to be much more open and broad-minded than today’s fundamentalisms) to reinvigorate it. Their work has an appealing blend of Romanticism and philosophical Realism (of reason, revelation, and experience) that is prefigured in St. Augustine’s Confessions. And their (wider, more inclusive) understanding of the grace of God helped address my most stubborn and profound spiritual misgivings. Grace, as I’ve come to understand it, is a universal force that acts upon the Zen monk and even the non-believer as well as the devout Christian. I like to think of its telos as the “vision glorious” (to borrow the words of nineteenth-century hymn writer S. J. Stone), the consummation of our deepest (or highest) desires: a world transfigured, bursting with life and startling depth, like celestial fireworks.

That spiritual detour came to an end in graduate school, with marriage and the prospect of fatherhood on the horizon. I decided to return to the faith (or a modified version of it) and to church. In the course of our children’s lives (and for reasons that were more geographical and personal than theological) we’ve attended Episcopalian, Presbyterian, Congregational, and now Quaker services. But it is the Quaker tradition that held most appeal for me in this latter stage, regardless of what denomination I was in. I would often refer to myself, in early-adulthood days, as a “neo-anabaptist” (signaling the influence of Mennonites and Brethren denominations as well as Quakers). What appealed to me about Quakerism, for reasons that won’t come as a surprise, is the strong sense of separation of church and state, or the strong critique of Constantinianism (a preferential status accorded by a national or imperial government to the Christian faith) that is part and parcel of it. The Religious Right (and now, Christian nationalism) yearns for the privileged status and top-down coercive power that Constantine first granted the Church, and the neo-anabaptist tradition offered me a ready-made alternative to that.

The Quakers, and like-minded groups, have long held that membership in a church (or meeting) is altogether separate from national citizenship. Both communities (national and ecclesial) have their own sagas, but the Christian one is much older—going back to the ancient Israelites, through the Prophets, Christ and the Apostles, and the Councils that gave us the Creeds, St. Augustine, and the Reformers. It is much more particular (but also much more global) than any national saga could ever be.

I’ve had major doubts and issues resolved (at least resolved enough) through the Quaker and Augustinian traditions to move forward on the pilgrim trail. But that doesn’t mean the quest is over. The lines from U2, which has always refused a simple partition between the sacred and the secular, still follow me along the trail (or in the silence of the Quaker meeting) like a mantra:

You broke the bonds

And you loosed the chains

Carried the cross of my shame

Oh my shame, you know I believe it.

But I still haven’t found

What I’m looking for

Mark Griffin is Professor of Spanish at Oklahoma City University. He was born and raised in Mexico, where his parents served as career missionaries. He is co-author of Living on the Borders: What the Church Can Learn from Ethnic Immigrant Cultures (Brazos Press, 2004) and has written articles on modern Latin American and Spanish literature.

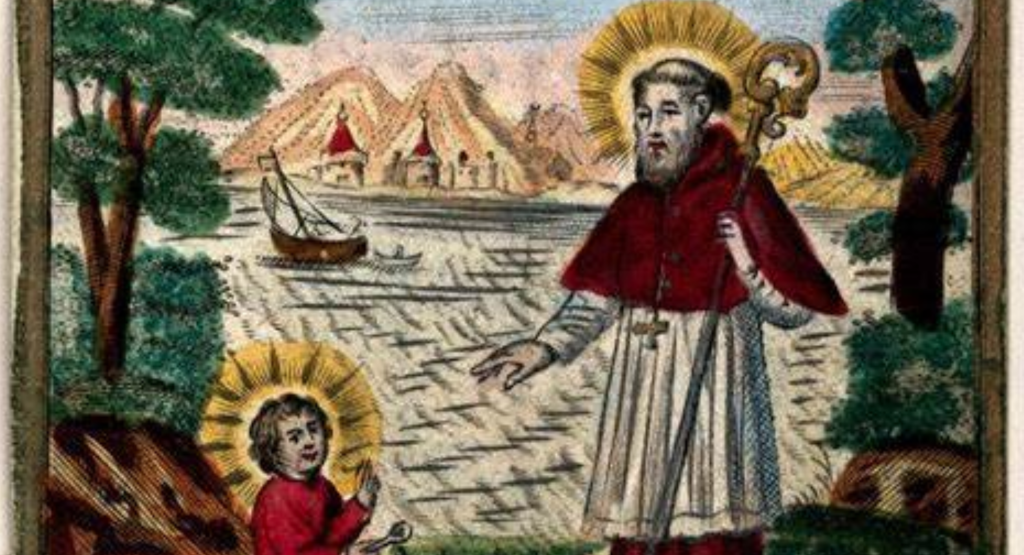

Image: Engraging of Saint Augustine of Hippo: by F. Huybrechts.