On the matter of public schooling, David French mistakes state authority for religious liberty

In the history of American politics the phrase “separation of church and state” has attracted strange bedfellows. The phrase has its origins in a letter Thomas Jefferson wrote to the Danbury Baptist Association in 1802. These Connecticut Baptists had written to Jefferson asking for his support in their struggle against the state-established Congregational Church: They objected to having to pay taxes in support of a Church to which they did not belong, and objected more generally to the idea of an established church that could exercise its authority over non-members. Though Jefferson himself had no political authority in Connecticut, he was at the time President of the United States and an acknowledged founder of the nation. He lent the Baptists his moral support, invoking the disestablishment clause of the U.S. Constitution as a model for the states and insisting that the Constitution created a “wall of separation between church and state.” Thus the Bible-believing Christians of the Baptist Association and the free-thinking deist who re-wrote the Bible to reduce Jesus to a wise moral teacher found common ground on the principle of religious freedom, understood narrowly as the freedom of individuals and groups to pursue their religious beliefs free from state interference in exchange for those individuals and groups renouncing all efforts to advance their beliefs through the state.

The recent decision by the Oklahoma state legislature to fund a Catholic charter school has resurrected at least one high-profile example of this old alliance. The editorial perspective of The New York Times stands as a rough contemporary equivalent of Jefferson’s enlightened secularism. The Times responded to the Oklahoma school case with an unsurprisingly negative assessment from a somewhat surprising source: the columnist David French. Readers of Current are no doubt familiar with French. Unlike most Times op-ed writers, French positions himself on the political right, even the religious right, albeit in its pre-Trump, Reaganite version.

Reagan-era Christian conservatives, such as those represented by Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, certainly saw problems in the public schools and wished to turn back the education clock to some earlier, more Christian-friendly era; still, few if any demanded that the state support Christian schools. In fact, the mission statement of the Moral Majority denied any explicit religious affiliation or agenda, insisting that it sought only to promote universal moral values. But in his article “Oklahoma Breaches the Wall Between Church and State” French sees developments in Oklahoma as crossing the line from shared values to religious establishment: “Charter schools are public schools, meaning that Oklahoma has created and sanctioned a Catholic public school in the state. It has clothed a Christian institution with state authority.” For French, this violates the time-honored constitutional principles of disestablishment and the free exercise of religion, which, he contends, have safeguarded an “extraordinary freedom and autonomy” for religious organizations throughout American history.

Churches have indeed enjoyed a high degree of freedom in the United States. Religious schools have not. It is perhaps only fitting that the first religious school to cross French’s constitutional line should be a Catholic school. French’s airbrushed history of church-state relations ignores the tremendous religious battles that marked the founding of public school systems in America. The Constitution makes no provision for education. Public education arose in the 1830s largely in response to the democratization of the electorate and the rise of immigration. Northeastern Anglo elites, fearing their loss of political power, looked to public education as a way of washing the unwashed masses, making them over in the image of the elites themselves.

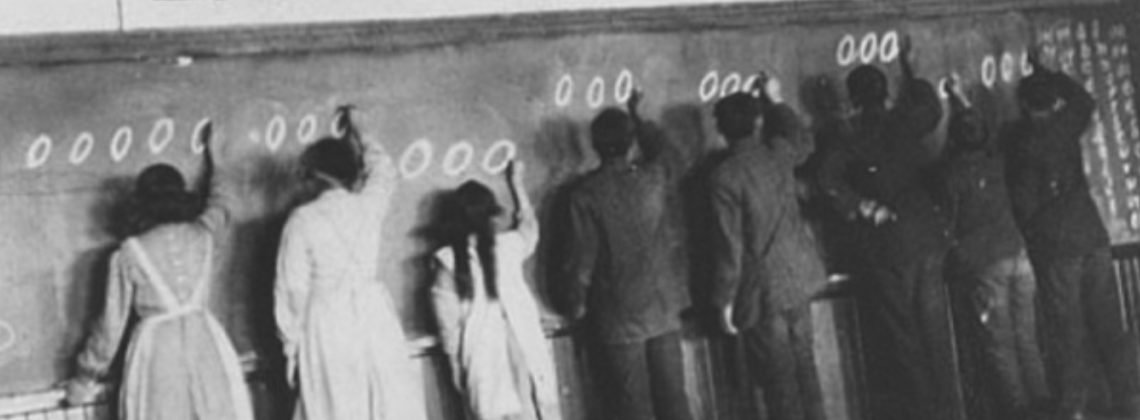

For a sense of the cultural ethos of these education reformers, think of the Unitarianism of Horace Mann, the figure generally credited with initiating and guiding the development of public schools. In Mann’s day, public school societies were in fact private institutions chartered by municipalities to perform a public function. Many Protestants objected to the education provided in these schools, fearing it was designed to turn their children into Unitarians. (They were right!) All involved agreed that morality was essential to education and that religion was the basis of morality. This agreement led to a compromise that religious instruction would be limited to daily Bible reading, without comment, to avoid contentious denominational interpretations.

Before the ink could dry on this intra-Protestant truce, Catholics objected that since the Church forbade Catholics from reading unauthorized translations of the Bible, such as the King James Version used in the school, Catholic children in public schools should be exempt from Bible reading. Nativist education leaders spun this into a Catholic plot to take over the schools. After much debate and more than a few riots, Protestants circled their wagons around the public school while Catholics moved on to establish a separate parochial school system.

French’s claim that Oklahoma funding for a Catholic school amounts to Church establishment sounds much like the response of the public school establishment to Catholics in the nineteenth century. To be sure, I do not read anything particularly anti-Catholic in French’s account; I think he would respond the same way if the new charter school were generically Christian. I do object to his formulations of this issue as a conflict of “liberty” against “power” and “freedom versus authority.” For French, the funding of a religious school is an act of power and authority that undermines liberty and freedom. What liberty and freedom have American Catholics had in education? Yes, the freedom to operate Catholic schools at their own expense—while continuing to pay for public schools through their taxes. How is this requirement to pay twice not an exercise of power and authority? Further, how is the state imposition of universal and compulsory requirement for education not an exercise of power and authority?

I am not sure what, if any, historical understanding of education in America informs French’s resistance to funding for religious schools. At one point he favorably quotes Justice William Brennan’s assertion that schools should prepare students “for active and effective participation in the pluralistic, often contentious society in which they will soon be adult members.” This civics-class idealism obscures the moral and cultural conflicts that have characterized public education throughout its history, particularly with respect to the Catholic Church. Despite the slavish patriotism that has animated Catholic schools from the beginning, the Church’s commitment to a separate education system reflected a fear that public school education was somehow a threat to the faith. Public school standards nonetheless exerted a powerful influence on the Catholic schools; as early as the 1890s some Catholic educators wondered what, if anything, made Catholic schools different from public schools aside from religion class. From the 1960s onward many Catholic educators came to believe that even the distinctly Catholic elements of religion class made Catholics stand too far apart from other Americans: Lest Catholic teaching make Catholics appear to be bad citizens, religious instruction should conform itself more to American norms. This development begs a key question: If religious liberty simply reinforces the authority of the state, in what sense is it liberty?

Ironically, American principles of disestablishment and free exercise have actually made it more difficult for churches to operate schools. Many European countries with established churches fund a variety of church schools with no fear of dissenting church groups taking over the state. The particularities of the American system may require a different approach to this problem. Perhaps a direct charter is not the solution. When I was a child going to parochial school in the 1970s, my parents and their friends fought for tuition tax credits—that is, the ability to claim Catholic school tuition as a charitable donation. This movement failed, its opponents invoking the sacred wall of separation between church and state. What we are left with is the persistence of an infidel tax, with Catholics who desire a Catholic education for their children having to pay twice. If fewer and fewer Catholics are willing to pay this, do we judge this evidence of religious liberty or state authority?

Christopher Shannon is associate professor of history at Christendom College in Front Royal, Virginia. He is the author of several works on U.S. cultural history and American Catholic history, including American Pilgrimage: A Historical Journey Through Catholic Life in a New World (2022), available now from Ignatius Press.

You say, “many Catholic educators came to believe that … religious instruction should conform itself more to American norms,” and then object, “If religious liberty simply reinforces the authority of the state, in what sense is it liberty?”

It sounds to me, from your brief description, that the educators in question, not “the state,” were the ones advocating changes? That doesn’t really sound like an infringement of liberty.

Unless it is the case that, as you go on to imply, any “conformity to American norms,” even if voluntarily embraced, is somehow a sign of a failure to exercise religious liberty?

One would need to examine the norms in question on a case by case basis to determine if they were consonant with the religious tradition in question. But isn’t a knee-jerk rejection of “American norms” as potentially harmful to the integrity of a religious community as any knee-jerk impulse to confomity?

Additionally, if it’s the case that a positive regard for “American norms” often emanates from within religious communities (rather than being coerced by the state in some way), how does establishing formally separate educational institutions remedy the problem (if it is “a problem”)?

(I’ll add that I think an attitude that regards any similarity with “American norms” with suspicion is essentially fundamentalist, but we can leave that discussion for another day.)

John,

Here’s a few “American norms” that American Catholic leaders found objectionable in the 1890s:

The primacy of private judgment in discerning ultimate truth, including a personal interpretation of the Bible even if it goes against Church teaching.

The need for a democratization of authority in the Church to conform to the norms of American politics.

The primacy of the active life over the contemplative life.

You will recognize these all as central to the controversy over “Americanism,” culminating in Leo XIII’s condemnation in 1899. This was in one sense a “phantom heresy,” since these ideas were only entertained by a small elite of intellectual Catholics at the time. By the 1960s, all of these ideas had entered the mainstream of American Catholic life and often taught by “enlightened” educators in Catholic schools. How did we get from point A to point B? Did all Catholics make free individual choices to adopt these American norms or were there structural pressures at work? Most historians tend to look to structures. I am not saying that the public school is the only factor, but it certainly is one factor, a major one, and the one under consideration in French’s article. Are you really saying that we should interpret the decisions of Catholic educators at face value, as simply “free” choices? So, when Walmart workers accept substandard wages, they are simply exercising a “free” choice because neither the state nor Walmart forces them to work for those wages? If you are so concerned about freedom, why are you not outraged that the state forces people to pay taxes for schools that they cannot in good conscience support? Or does the fact that Catholics have never as a group withheld tax payments for schools in protest satisfy your standard of consent?

I believe the author is in error about Catholic schools being a response to public schools that emphasized Protestant thinking. Rather, my studies have indicated that establishment of public schools were in response to the growth of parochial schools established by the Catholic church. This may, of course, have varied by region or even neighborhood.

I think the author of this piece needs to do a bit more background work on French instead of trying to use him as a convenient foil. David has spent much of his career working for religious liberty. And he is not opposed to Christian or even Catholic schools (one of his kids is currently in a catholic school.)

And he is a proponent of voucher systems that fund catholic and protestant schools.

His objection is the direct funding of religious schools through direct taxes instead of indirect methods like vouchers. Direct funding is state sponsorship of religious functions. In cases like funding of social services by religious organizations, there are rules against funding being used for religious purposes. Which is not being done here (there is funding of direct religious purposes.)

Chris,

You ask: “Did all Catholics make free individual choices to adopt these American norms or were there structural pressures at work? … Are you really saying that we should interpret the decisions of Catholic educators at face value, as simply ‘free’ choices?”

I didn’t actully use the term “free” or any cognates in my comment. What I did note–and which you agree with, as your invocation of “structural pressures” reveals–is that Catholic rapprochement with “American norms” wasn’t coerced by the state in the same way, eg, that filing a tax return might be.

Nevertheless, if your idea of “free” means not only legally uncoerced, but utterly immune to any influences exogenous to whoever or whatever is making the choice, then, no, I agree with you, these probably weren’t “free” decisions. Indeed, I’ll see that and raise you: On that definition, there’s no such thing as “a free decision.”

You also ask, “why are you not outraged that the state forces people to pay taxes for schools that they cannot in good conscience support?”

You’re right, I’m not outraged by that. My lack of outrage in that regard is a subset of my more general view of taxation as it currently exists: Taxation isn’t at all predicated on “good conscience support,” but rather on the brute fact that any given citizen is a member of a community that has decided, by way of representation, to engage in such-and-such activities and endeavors and has agreed to pay for them.

Along those lines, I wonder if Catholics’ absence of “good conscience support” for the public education system runs as deep as you apparently assume? Or, if it does, then whether it should, given their organic understanding of society and commitment to the common good?

Clearly Catholics, like others who have parochial objections to various aspects of our public education system as presently constituted, nevertheless benefit in uncountable ways from that very system, even if they don’t enroll their children in the system, or have no children themselves. Even an intellectually unrigorous and arguably religiously defective public education nevertheless benefits all members of a society by equipping that society’s members with skills and capacities that they otherwise would lack, and those skills and capacities redound materially to the prosperity, peace, and safety of the society in question and all its members, even those with the most strenuous conscience objections to that very system.

I suspect many or most Catholics recognize this, insofar as they are employers, employees, dependents of same, neighbors, and fellow-citizens affected by the aggregate actions and decisions of these students. If they do not, they should. (Indeed, the robust and admirable tradition of Catholic social thought positions them far more favorably to appreciate these realities than do the primitive and naive individualistic assumptions of the average Protestant.)

Lastly, you ask “does the fact that Catholics have never as a group withheld tax payments for schools in protest satisfy your standard of consent?”

There are, of course, levels of consent and dissent (as our use of Likert scales, eg, reveals). As indicated above, our entire system of taxation is predicated on the assumption that communities and individuals will have many objections to the specific allocations and projects the nation may assume, but that a willingness to go along with the system and to work for changes, when desired, by operating within that system rather than engaging in civil disobedience, is a significant indication of at least qualified dissent.

In this, if that’s the case, they are obeying the mandate of Jesus, whether they know it or not. When he said (Mark 12), answering the Pharisees and Herodians regarding the imperial tax, “Render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s,” while holding up a coin with the emperor’s image (that also identified him as divine), Jesus was indicating that the tax was, broadly, just. The Greek word translated “render” means not just “pay,” but “pay back,” indicating that the tax is compensation for government services provided that, while not bringing in the New Jerusalem, do make for the “peaceful and quiet lives” that Paul (I Timothy 2) indicates is the point of civil government.