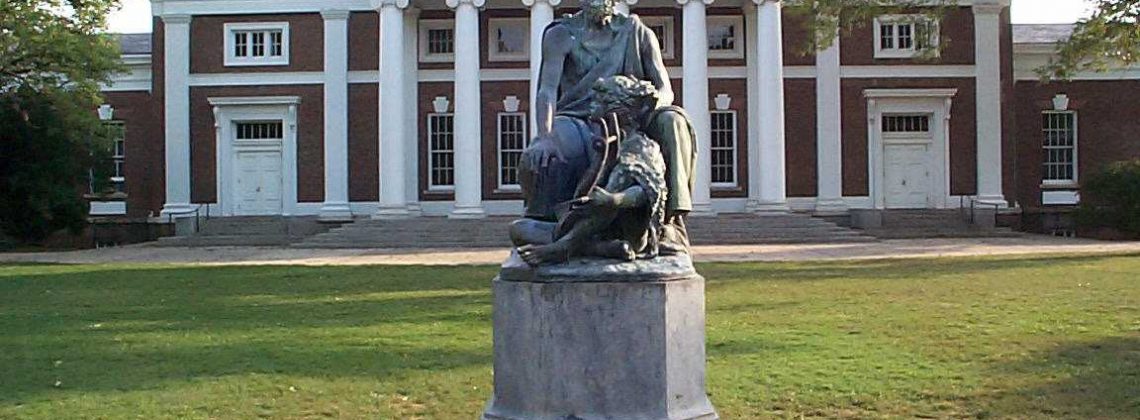

On a sweltering mid-August day in 1999, the day before I began my first year of college at the University of Virginia, I timidly knocked on the office door of the legendary David Kovacs, a world-known scholar of Euripides (although I did not know that at the time), and declared my major in Classics. He asked me at the time what I thought I would like to do with my degree, and I confidently responded that I knew that I wanted to pursue a PhD in Classics and become a college professor.

What I did not have the words to express at the time but do now, is that I felt a sense of calling—vocatio, to use the Latin term. I still feel this inexpressible giddy joy whenever I get to teach, write, or talk about the ancient world. I want to impart this joy to my students and anyone who reads my work, while showing them that the ancient world, seemingly so strange and far removed from us, both geographically and temporally, is very relevant to our lives today in a variety of ways.

But one thing that I did not foresee back in 1999 or even in 2008, when I completed my PhD in Classics, was the assault on the humanities that would significantly impact my professional life. The decline of jobs in Classics in 2008 and after meant that I ended up in a History department in a university that does not have a Classics department and does not offer any Greek or Latin (although I teach both on occasion as special topics courses). More alarming, the past decade has seen the shuttering of multiple Classics departments across the country. Worst of all, the Classics have been the canary in the coal mine that is the state of the humanities in higher ed, as is becoming apparent of late.

And now, as a humanities faculty member teaching in a regional state university in the South, I have been following with sadness the unfolding takeover of Florida higher education by Republican Governor DeSantis. I identify as a conservative, but these developments give me no joy. My university system has had to deal with similar interference over the past two years, and I wrote about this for Current last year. To be clear, I would not welcome the takeover of public education by any group. The entire point of public education is that it should reflect the interests of the public, not one individual or group. Anyone who desires education from a particular perspective would be well served finding a private college or university that provides it.

So far, I have seen a range of reactions to the developments in Florida—from glee from some circles over the perceived deserved comeuppance for the liberals, to sorrow from other groups over the complete disregard of academic freedom, and grief over the treatment of faculty uniformly as the enemy by the state.

But there are two related issues that deserve further attention, and both of these ultimately have to do with the group of people who are going to be the most profoundly influenced by these changes: the students. First, inextricably linked to any such takeover is the devaluing of the humanities in favor of professional programs at so many state universities. The accusation of humanities disciplines as propagating liberal agendas has simply become the latest (and, admittedly, politically savvy) excuse for obliterating the humanities altogether. Indeed, at the time of this writing, my own institution is openly removing support and funding for humanities programs in favor of creating new technical degrees, some of them two-year degrees, rather than four-year.

Second and related, there is a larger looming issue that this shift in public higher ed reflects that has not yet received sufficient attention. This issue is the rise of utilitarianism as the governing philosophy of higher education. This philosophy only sees jobs and students as abstract and interchangeable entities. If the state needs a certain number of new nurses or engineers or construction site managers, then we will produce this particular number of graduates in these degree fields, and that is all.

In this utilitarianism, there is no consideration of the students’ souls and, therefore, no desire to cultivate their sense of discovery of vocation as something greater than just a way to pay the bills. Instead, the philosophy is: get them into paying jobs, and that is all that matters. Too bad if some of the students who got pushed into particular fields because they will get them jobs, realize too late, after obtaining the requisite training, that they do not actually want to work in these fields.

There is some legitimate logic to this line of thought that looks so simplistically at the calculus of matching students to the number of jobs: at the end of the day, everyone indeed needs to be able to pay their bills. But is this the extent of human flourishing we desire for today’s youth? Besides, this utilitarianism in public education is hostile to educating the whole person. As the push to reduce the core curriculum implies, why does a nurse or a crane-operator need to appreciate literature or know history anyway?

But such a philosophy of education disregards well-ordered human anthropology with disastrous results. Whether we openly recognize it or not, we are wired with a desire for something greater, something beautiful than just being cogs in the industrial machine. It was this desire, I think, that gave me such incredible joy when I was first able to read Vergil’s Aeneid in Latin as a high-schooler. In fact, poetry is a great example of our inner wiring and its instinctive resistance to utilitarianism: we love it not because it does anything practical. We love it because it is beautiful. It is this same desire that I now see in my homeschooled third-grader, whenever he figures out a sentence in Greek. The joy of a difficult puzzle is gratifying, even if the puzzle, in this case as well, holds no practical significance. But then we could say this about so much of the intellectual life.

The utilitarian approach to education and jobs ignores people’s desire for beauty and a sense of deeper purpose, and contributes to the deep burnout that so many experience—just see David Kee’s book review on this topic just last week. A mismatch between what one does in one’s job and one’s innermost desires (the search for a true vocation!) leads to burnout. I think about one student I taught recently, who came back to get a second college degree, because he realized that he hated his job as a pharmacist. He is now finishing a second BA in History, and plans to become a high-school history teacher.

And so, Wendell Berry’s poignant commentary on the reduction of work to just “job” in his recent book, The Need to Be Whole, has been sitting heavy with me since I first read it several months ago:

“Perhaps because of our acceptance of the reduction of work or life’s work from vocation (“calling”) to “job,” many people now speak with conventional dislike of their working lives, apparently longing through their workdays for quitting time, the weekend, vacation, and retirement. They are thus not willingly living, much less enjoying, the most necessary and significant hours of their lives, but are wishing them away. This surely is a sort of death wish. How can workers think well of themselves if they do not think well of their work?”

We were created for more than this.

I know someone who did a very practical, technical, two-year training program and then could not get a job in that field (I think that sector had moved on and what they were trained on was no longer standard practice). They had a lot of debt resulting from their “higher education”, but had not received an education nor had their training led to a job. They ended up in a clerical job at a car dealership that did not require any advanced training (and which they hate). The line in this post about students having souls is wonderful – a true education is a gift that can nurture a person throughout their life – through periods of unemployed, unsatisfactory employment, illness, and more.

In the same vein, I know liberal arts majors (English, history, etc.) who are floundering and working as baristas. It doesn’t have to be this way. All public colleges do not completely succumb to utilitarianism (public liberal arts colleges) and some private colleges also embrace utilitarian ends. There are those who are calling for a renewed focus on the “soul” of learning, and they vary in their deep beliefs and solutions. Steve Volk and Beth Benedix offer a “manifesto for reinvention” that challenges the way college systems promote inequality and racism (The Post-pandemic Liberal Arts College, 2020, Belt Publishing). They call for a humanistic and holistic reinvention, with a set of values at the heart. Other colleges work toward human flourishing from within more traditional, classical-valuing communities. Various organizations, such as the AAC&U attempt to provide guidance for how colleges can promote human well-being in ways that both provide resources for daily life and deeper meaning-inducing ways of being in the world. The pharmacist who becomes a history teacher may well find joy, but will also have to deal with the very real challenges of low pay, lack of respect from the public, and the realities of schools. There are riches to mine in ancient texts, but many children can’t read basic works (an admittedly challenging problem). With the explosion of knowledge available, media and other technology dazzling our senses, and news feeds offering up disaster, pain, and suffering in droves each day, what are we to do? How can those of us who live in a global society now both benefit from and critique the western canon as well as non-western cultural artifacts? John Inazu speaks of “confident pluralism” as a way toward hope. My own Christian tradition offers hope and redemption in the Christian gospel, yet I see it abused daily. Will the virtues of Greek language and story inculcate the good life? Will it create noble humans? If such education makes for virtuous transformation, then it should be made available to all. Competing visions for life and learning exist, but remain committed to seeking a way to reimagine learning (at college and other levels) that is broad and deep enough to feed the soul, provide beauty and sustenance to all humans, and do it in the 21st century. Perhaps I am crazy…..

I really appreciate these thoughtful and nuanced responses that highlight just how complex this topic is in our present cultural context. Dan Williams will provide another complicating piece of this puzzle in his blog post this Thursday.