Georgia’s proposed bills overlook one crucial truth: It’s the truth that sets us free

On July 10, 1941, in the town of Jedwabne, Poland, the Polish residents of the town rounded up the town’s Jewish residents in a barn and set it on fire. But what sets the story of Jedwabne apart from other, more famous tales of horrors from the Holocaust is the documentation (including photographs) showing that in this case it was not the Germans who murdered the Jews. Rather, it was a case of neighbors murdering their own neighbors, with whom they had lived side-by-side in that small town for centuries. One half of the town killed the other half, as historian Jan Gross and journalist Anna Bikont show in their respective books Neighbors: The Destruction of the Jewish Community in Jedwabne, Poland and The Crime and the Silence: Confronting the Massacre of Jews in Wartime Jedwabne.

And yet Jedwabne is not the only town in Poland with such a tale. It simply has the distinction of being the best documented. So how does a nation come to terms with such national sins, especially when they are still so near to living memory? How does a nation talk about collective sin, guilt, and complicity? In the case of Poland, as Bikont shows, the solution has been largely to not talk about it—although sometimes, Marci Shore notes in The Taste of Ashes: The Afterlife of Totalitarianism in Eastern Europe, the locals do still use the infamous barn as a landmark for giving directions, as casually as one might tell someone to take a right at the next McDonald’s.

In 2018, however, the Polish government went farther than its previous policy of informal silence: It passed a bill “that outlaws blaming Poland for any crimes committed during the Holocaust.” As one lawmaker who supported the bill explained, “We have to send a clear signal to the world that we won’t allow for Poland to continue being insulted.” The penalty for violating the law? Up to three years in jail.

Faced with an international outcry over its attempts to rewrite history, Polish lawmakers softened their stance five months later, making it a civil rather than a criminal offense. The slight modification of the law, of course, was not the result of any of the lawmakers really changing their minds on the historical questions at hand. “Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki said he still believed that those who said Poland was responsible for Nazi crimes deserve to be in prison. But he conceded that his government must take into account the international context.”

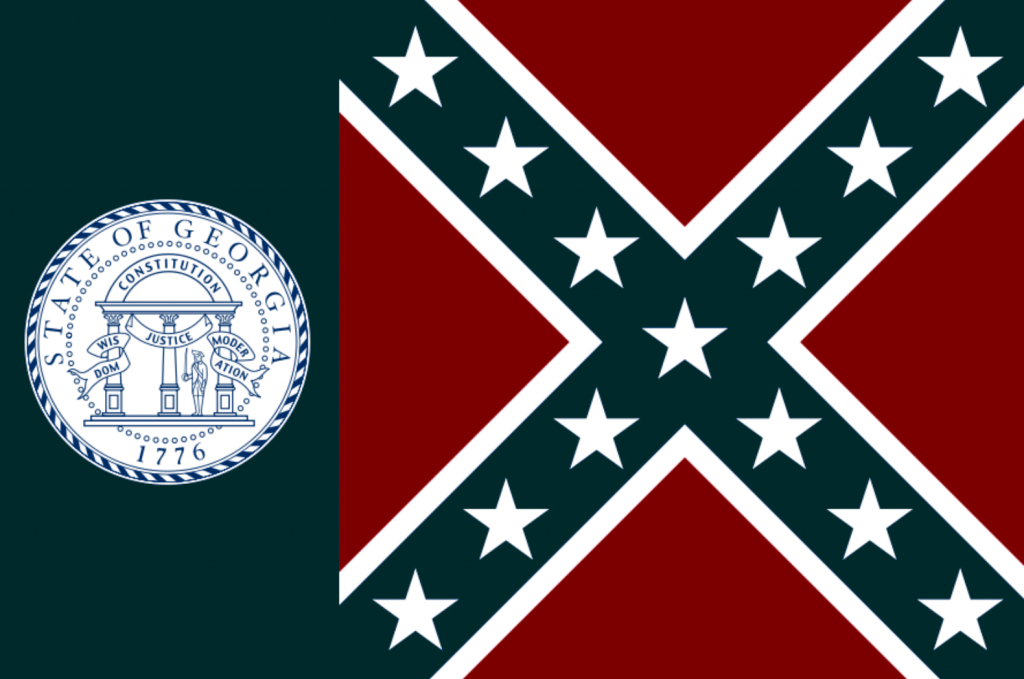

Poland’s largely unrepentant treatment of past national sins through forceful gag orders hits close to home now, as multiple states, including my current home state of Georgia, are considering passing laws that will effectively do for teaching about racism in America what these Polish laws have done for speaking about anti-Semitism and complicity in the Holocaust in Poland. To be clear, I am not saying that there is a direct parallel between the two situations. And yet, considering the horrific legacy of systemic racism still present in the US—including, for instance, at least eight suspected lynchings in Mississippi since 2000—there is an uncomfortable echo in these unrepentant white-washings of history.

Georgia’s proposed bills, SB 377 and HB 888 are specifically concerned with how issues of race are taught in Georgia’s public schools and universities. Both propose heavy financial penalties to schools and universities found guilty of violations. And they very likely will pass this spring, given the overwhelming Republican support.

So what kinds of topics are off the table? SB 377 forbids state employees from teaching any “divisive concepts,” such as the notion that either the U.S. or the state of Georgia is systemically racist. Also forbidden is teaching that “An individual, because of his or her race, skin color, or ethnicity, bears responsibility for actions committed by other individuals of the same race, skin color, or ethnicity, whether past or present.”

It gets worse. HB 888 argues that “Slavery, racial discrimination under the law, and racism in general are so inconsistent with the founding principles of the United States that Americans fought a civil war to eliminate the first, waged long-standing political campaigns to eradicate the second, and rendered the third unacceptable in the court of public opinion, all of which dispels the idea that the United States and its institutions are systemically racist and confutes the notion that slavery, racial discrimination under the law, and racism should be at the center of public elementary, secondary, and postsecondary educational institutions.” In other words, there is no such thing as systemic racism, so stop teaching anything that might hint to the contrary.

The bill also enthusiastically adds, “Americans should be allowed, in the words of civil rights activist Robert Woodson, ‘an aspirational and inspirational take on America’s history, debunking the misguided argument that the present-day problems of black Americans are caused by the injustices of past failures, such as slavery.’”

It seems that current Georgia lawmakers and their brethren in thirty-six other states would get along quite well with the Polish legislators who passed the gag order outlawing blaming Poles for Nazi crimes. But as a conservative evangelical, what I find particularly problematic with the present set of laws is the fact that they are being proposed by fellow evangelicals—individuals who, like me, claim to have been redeemed and washed clean from past sins by the blood of Jesus. I find theologically flawed the utter refusal latent in these proposed laws to acknowledge past sins and any need for repentance.

Marci Shore has aptly noted that Jan Gross’s research into the Holocaust has at its root been about investigating why evil exists. For Shore, a secular Jew, there is no way to answer this question in considering the sins in Poland’s past. For evangelical Christians in the U.S., however, there is definitely a path for addressing this question. As Tracy McKenzie argues in his recent book We the Fallen People: The Founders and the Future of American Democracy, the path for engaging with the more challenging episodes in American history, the ones that it might seem easier to forget or ignore, involves remembering the doctrine of original sin.

If we remember, as McKenzie urges, that we are deeply fallen, then we will recognize that it is not unpatriotic to say that the United States has national sins. Rather, acknowledging such sins is theological orthodoxy, simply because original sin is our common heritage as humans. We need to keep this in mind when Christian nationalism blinds us to such national sins as those currently being expunged from curricula.

Acknowledging national sins is not a betrayal of America. It means repentance and acknowledgment of God’s sovereignty over our own feelings of self-righteousness or the desire to be seen as better than we truly are.

What might such repentance look like? One moving example involves the repentance of Historic First Presbyterian Church of Montgomery, Alabama. The entire church’s decision to repent led, in the process, to the discovery of yet more sins—but also to the reconciliation of families. The painful nature of the process for this church is a reminder of how difficult seeking such repentance is. In engaging in repentance, this church certainly ended up discussing what Georgia lawmakers would label “divisive concepts.” But it was precisely the open discussion of these divisive concepts that, ultimately, made reconciliation possible, and the hope of future unity as well.

Nadya Williams is Professor of Ancient History at the University of West Georgia.

“Acknowledging national sins is not a betrayal of America. It means repentance and acknowledgment of God’s sovereignty over our own feelings of self-righteousness or the desire to be seen as better than we truly are”

Amen. It has been shocking to watch ‘the race’ to totally erase America’s sins today. They are never to be taught about, read about in books in our School libraries, or discussed in classrooms.

Pride comes before a fall.