How useful are historical analogies in our new political era?

It’s a popular pastime among historians to assert—and then argue over—analogies. Dred Scott, the 18th amendment, and Brown have each served as analogies in the abortion debate. A writer here has proposed this last one: Our current landscape regarding abortion is like that created by the rightfully famous Brown decision overturning Plessy, thus making it illegal for states to mandate racially segregated schools.

It is true that Dobbs, like Brown, reversed a long-standing precedent. Both decisions extend rights to some, take them away from others, and hence are controversial.

But are analogies with the past the most illuminating way to view our moment? It seems more useful to recognize we are in a unique era, constitutionally and historically, of assertive federalism. America’s fifty regional subdivisions are taking back power from Washington, D.C., a movement that has been building since the 1970s. Call it an extended backlash against the Warren and Burger Courts, if you wish.

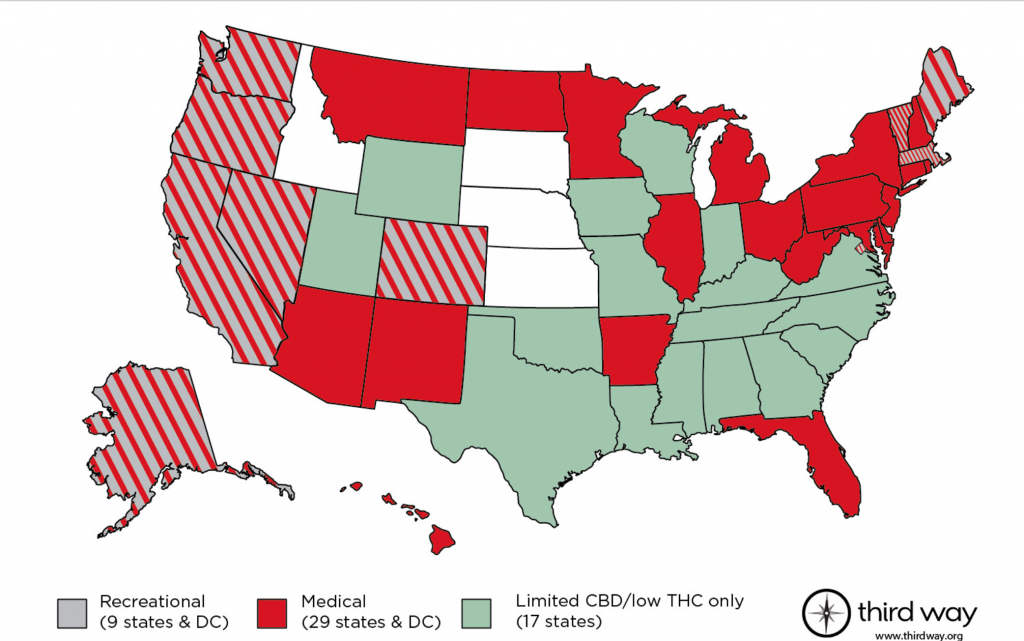

A better comparison is with another contemporary development: state-level permissions or prohibitions of marijuana. (Our current situation occurred apart from any action by the Supreme Court or Congress, but the federal government has adopted a posture of non-interference in state marijuana policies.)

In states such as mine that prohibit the use of marijuana, millions of residents obtain it illegally on the underground market, or by traveling to states where it is legal, or by ordering it through the mail. Likewise, in neighboring Michigan, where marijuana is legal, millions of residents there decline to use it as a matter of individual choice.

Brown didn’t put the decision whether to mandate segregated schools under the control of state legislatures. It (ostensibly) disallowed segregation, whatever a state might wish. The Dobbs decision is just the opposite of Brown, considered from this angle: It takes the federal government out of the equation, reversing Roe’s federal interference with state law. States are now in control of the legal aspects of abortion, and the federal government isn’t likely to strike down whatever regulations a state might wish to remove or put in place—just like state-level marijuana policies.

Regarding marijuana, no one is required to take advantage of liberalized laws in states permitting its use, and those residing in states that ban the substance will still avail themselves of it despite state prohibitions. Millions of Americans living in states with liberal laws will choose not to use marijuana, just as many citizens living in states that ban it will use it nonetheless.

Abortion now resides in a parallel context where state law and individual choice are, together, determinate. (Obviously, individual choice is constrained in states prohibiting abortions, but some number of those citizens will obtain them nonetheless, just as they now obtain marijuana.)

National legislation is no longer the determinant of whether an abortion occurs or not. It is rather up to the individual who can opt for one in accord with the law of their state. Or despite its illegality in their state, they might choose to have a legal abortion in another state. Or they might choose not to have an abortion for conscience or other reasons.

Our current situation has consequences for how we view the political process and the choices we make in that sphere.

For a pro-life person like myself, my (national) electoral choices are removed even further than before from abortion as a social reality. The federal government no longer controls abortion law in my ruby red state.

A pro-choice citizen might dream of overturning Dobbs someday, but with five of the concurring justices decades away from retirement, that dream is far from realization.

In swing states such as Michigan voters have room to see their preferences instantiated at the state level, but there are no federal remedies should state law depart from those preferences. Even with state law being whatever it will become, it will in most cases still be an individual decision whether to have an abortion or not. Just as in Michigan it is up to the individual whether they choose to use marijuana or not.

The idea of “voting pro-life” has largely vanished, at least as far as that’s been typically understood. Voting for the Republican candidate for president is no longer an effective way to see one’s convictions expressed as the law of the land (if it ever was). Tens of millions of voters who are concerned about the unborn are now free to evaluate presidential candidates on their merits. The process is no longer complicated by the abortion issue, as it was in the past.

Under the Roe-Casey regime many pro-choice voters who also leaned libertarian in areas such as taxes and business regulations had to choose between their economic values and their support for “reproductive freedom” when voting in national elections.

Similarly, millions of pro-life voters often found themselves in a quandary, preferring a more positive state when it came to welfare, the environment, and refugees, but unable to find a viable candidate who reflected those views without also affirming abortion-on-demand in a way that was well to the left of even most European polities.

Such dynamics no longer hold in national elections, at least not with any urgency. A vote for the Democrat in 2024 won’t bring back Roe. A vote for the Republican won’t change New York’s liberal abortion laws.

And if it’s abortion rates we are concerned with, they’ve been declining steadily since the early 1980s. It’s hard to see how the party of the president will affect those at all.

This is welcome news to voters like me. For those of us who are concerned about the deep and long-lasting effects of Donald Trump and his enablers, who feel morally obligated to vote in a way that prevents further assaults on our democracy from that quarter, that Dobbs has been decided and is not going anywhere for some time allows for a clearer view of the contenders for the White House and a less complicated assessment of their merits.

This is neither the 1920s nor the 1950s; neither alcohol nor segregation is the burning issue facing us. In the twenty-first century it is the fate of the republic that’s at stake.

John H. Haas teaches U.S. history at Bethel University in Indiana.

Except you misread what *Dobbs* did. It didn’t return abortion to the states for resolution, though that is the effect at present. Rather, it removed constitutional protections for abortion, and leaves it up to elected officials, either at the state *or federal* level, to resolve. There has already been a (failed) attempt to enshrine the protections of *Roe* in federal law; there will undoubtedly be an effort to restrict or prohibit abortion on the federal level. This is not to mention the efforts on the part of some states to attempt to restrict access of their citizens to abortion in other states, raising a host of constitutional issues. For pro-lifers and pro-choicers, control of the federal government will continue to be a priority, and thus abortion will continue to be a federal issue

The Kaiser Family Foundation summarizes our current arrangement: “It is now up to each state to establish laws protecting or restricting abortion in the absence of a federal standard. Access to safe legal abortions now depends on where you live and the national divide in access to abortion care has been intensified.”

https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/press-release/abortion-in-the-united-states/

A senator praises Dobbs in these terms: “the fundamental principle of federalism is restored. This ruling reaffirms the tradition of the State of North Dakota to protect every human life …”

https://www.cramer.senate.gov/news/press-releases/sen-cramer-statement-on-dobbs-v-jackson-womens-health-organization-scotus-decision

A professor of social science, lamenting Dobbs, observes that the decision leaves it to “each state to decide whether or under what conditions abortions shall be legal within them. … Above all, Dobbs further entrenches states’ rights … It enshrines states as sites of democratic self-determination and bulwarks against federal overreach.”

https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/2022/06/27/alito-dobbs-decision-states-rghts/

On the other hand, a professor of government notes that abortion had already crept into national politics prior to Roe–a senator in 1970 introducing a bill legalizing abortion in Congress, the president in 1972 supporting the repeal New York’s liberal abortion law–and predicts such efforts will continue, post-Dobbs.

No doubt. The relevant question of course is to what degree such efforts will shape national politics, and thus control the decisions of large numbers of voters when assessing their options?

The future is notoriously open, and no discipline equips us to predict it accurately.

However, we can see this: whatever noises politicians working at the national level might make, Congress has no history of providing firm direction on the question, the United States does have a robust history of regulating abortion at the state level, and–for now–the Supreme Court has embraced the states as the only constitutionally appropriate venues for deciding the question.