If politics is in and evangelism out among American evangelicals, are they really evangelicals?

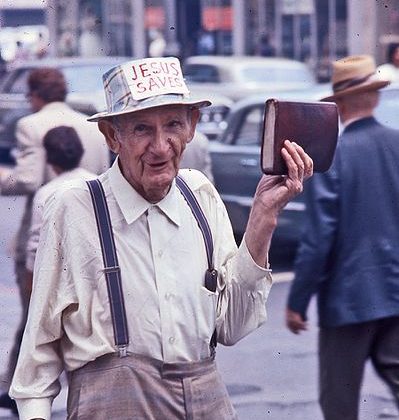

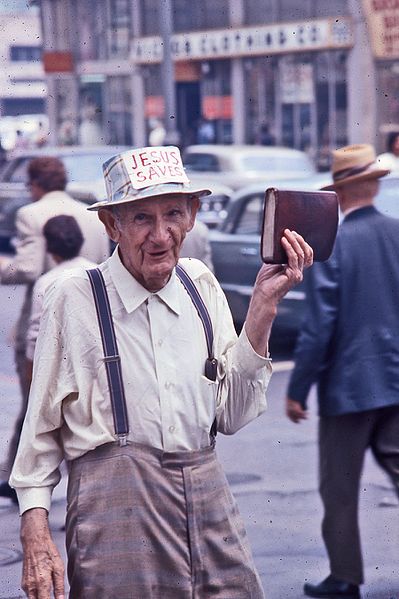

As a Catholic committed to spreading the Gospel, I have always had a certain respect for, even envy of, the Evangelical ideal of the street preacher standing on the corner shouting about Jesus. It has certainly seemed to me closer to the biblical model than anything I was ever taught about evangelization in twelve years of Catholic school. Come to think of it, I cannot really remember being taught anything about evangelization in my twelve years of Catholic school.

Thus, I was somewhat taken aback by a recent exchange between Bishop Robert Barron and Evangelical theologian Matt Jenson at a discussion of “Proclaiming and Encountering Christ in the 21st Century,” hosted by Biola University. Bishop Baron is, in my view, the leading Catholic evangelist in America today, doing his best to make up for the relative evangelical silence of Catholics during the generation of my young adulthood. At the end of an hour-long discussion stressing the common challenges and concerns of Catholics and Protestants, Jenson asked Bishop Baron what Catholics and Protestants could learn from each other. Bishop Baron stressed his respect for Evangelicals’ knowledge of scripture and ease with talking about Jesus. For his part, Jenson, reflecting on the weakness of the Evangelical tradition, noted meekly that Evangelicals are too inclined to see religion as a private matter, to keep it to themselves, to stress personal salvation.

What? Evangelicals are insufficiently evangelical? What about all the talk in the media about white Christian Nationalism, a shorthand term for Evangelicals trying to impose their religious views on America?

I suppose Jenson might respond that MAGA Evangelicals are not really Evangelicals at all. Liberals love to see theocracy lurking behind every political intervention by anyone claiming to be Christian, but there is certainly no discernably Christian agenda behind Trump’s demagoguery beyond simply the politics of respect and recognition—though one that, with a distinctly Trumpian twist, depends on the continued stoking of a politics of resentment flowing from the liberal contempt for all things Christian.

But Professor Jenson’s comments seemed directed at the more conventional, non-political notion of evangelization, my ideal Bible-thumping street preacher. Is this a thing of the past? I have to admit that having lived for roughly twenty years in the Shenandoah Valley, ostensibly part of the Evangelical Bible Belt, I really cannot recall ever encountering a street preacher, and only once or twice have I gotten a knock-on-the-door invitation to “come and worship” at a local non-denominational church. Front Royal, Virginia has plenty of Evangelicals but not much apparent zeal.

How different this all is from my first encounters with Evangelicals in the North during the seventies and eighties, the golden age of “Born Again” Christianity and the rise of the Christian Right. In these developments I was no mere Catholic sideline observer. My two brothers both became Born Again Christians, joining the ranks of the second-largest Christian denomination in America: Ex-Catholics. In the first years following their conversion they were “on fire for Jesus.” Their evangelical zeal came complete with a foundation stone of the Old Time Religion: anti-Catholicism. I was treated to the constant barrage of anti-Catholic accusations, courtesy of “The Catholic Chronicles,” a pamphlet series produced by Christian musician Keith Green. Beyond the specific errors of the Church, my brothers spoke of their own experience of the spiritual shallowness of their Catholic upbringing. The Church had reduced faith in Jesus to a bunch of rules and external forms. Catholics just went through the motions, had no personal encounter with Jesus, etc. The Church further proved itself false by its lack of zeal for spreading the Gospel.

Well, my brothers sure got zeal from their conversion experience. Both became ministers, one of them even a missionary to Brazil. If only for the purpose of family peace the heated exchanges on doctrine and the damnation of Catholics gradually faded into the civility of silence. Looking back, what strikes me most is that these exchanges were actually about doctrine and salvation, not politics. I cannot recall either of my brothers ever bringing Jerry Falwell into our debates over Christian Truth; I certainly was not looking for or expecting to find a political agenda in their conversion. In trying to understand the broader evangelical world I watched cable TV shows such as The 700 Club. Pat Robertson would run for President in 1988, but in the early eighties he still seemed focused on the salvation of souls.

The times they were a-changing and evangelical zeal seemed to drift away from personal salvation. My brothers both eventually left their ministries and returned to “civilian” life, still Christian but increasingly disaffiliated with any particular church, continually disappointed with “institutional” Christianity. Evangelicalism became more mainstream and perhaps less evangelical. The key moment for me is less Robertson’s presidential bid than the makeover reflected in the Christian Broadcasting Network becoming “The Family Channel.” Political evangelicals would use “family values” much as Catholics once tried to use “natural law”: a neutral language with which to promote ideals easily recognizable as rooted in particular religious beliefs. Evangelicals developed an army of family policy wonks through conservative think tanks such as the Family Research Council. For some, the family was a stalking horse for Jesus; for others, the family became Jesus.

The 2004 Christian Coalition meeting John Fea referenced in a recent Current piece captures this shift. Marilyn Musgrave’s effort to oppose same-sex marriage in the neutral policy language of think tanks met with a stern rebuke from an “Old Testament prophet” who insisted on a more straightforward denunciation of gay marriage as a sin. Musgrave comes across as the hero in Fea’s account, a model of civil public discourse, capable of speaking to the world in the language of the world. The zeal of the Old Testament prophet was, by implication, uncivil. Although I am something of a social science sceptic, I can appreciate Musgrave’s efforts to speak in a policy language accessible to non-Christians. Yet Christianity is also a language of the world—it is in fact still the language of many, if not most, Americans.

Any Christian politician—indeed, any Christian—speaking in a pluralistic society needs to be able to speak more than one language. But by the same token, a public sphere unwilling to allow Christianity as one of many different public languages is itself uncivil. Perhaps Matt Jenson’s comment about Evangelical reticence reflects the triumph of Musgrave’s model of civility. The political Evangelicalism born in the late 1970s seems to have followed a trajectory similar to the Catholic labor movement and the Protestant Civil Rights movement earlier in the twentieth century: from Christian public discourse to a privatization of faith and an idolatry of politics. I think the liberal media, and concerned, anti-Trump Evangelicals, are, for different reasons, too quick to blame Evangelicals for MAGA. My brief scanning of the survey data suggests that among self-identified Evangelicals, there is actually a negative correlation between active involvement in a church and support for Trump. Perhaps all this simply reflects the current difficulties with defining what it means to be a “true” Evangelical.

Media pundits continue to try to analyze the “Catholic vote” long after the data clearly show that there is no such thing. Maybe it is time to start to reconsider the usefulness of something called the “Evangelical vote.” One of my Evangelical brothers leans right, the other leans left. As I am not sure that it makes sense to call Nancy Pelosi a Catholic politician, I am not sure that it makes sense to call Ted Cruz an Evangelical politician. In public life, they clearly worship gods other than Jesus Christ.

Christopher Shannon is associate professor of history at Christendom College in Front Royal, Virginia. He is the author of several works on U.S. cultural history and American Catholic history, including American Pilgrimage: A Historical Journey Through Catholic Life in a New World, due this month from Ignatius Press.

I disagree with this: My brief scanning of the survey data suggests that among self-identified Evangelicals, there is actually a negative correlation between active involvement in a church and support for Trump.

I left my evangelical church 5 years ago, as the only openly Democrat I was subjected to endless “jokes” and mocking, and saw many of the church family posting on fb and actively working for t and just recently for Youngkin. That church is just down rt 66 from the author. Only mainline churches seem to have a mixed political membership.

In the oughts I suggested to high school seniors in my Government class that Christians could be Republicans and they could be Democrats. It was towards the end of the class and some students were enraged. Other teachers asked me what happened in my class that caused such a ruckus. There were those completely convinced that you could not be both Christian and a Democrat. I taught this class in my Christian school for 30+ years. I always made the point that good citizenship involved being favorable to one of the two major parties. It was my view that third party participation was essentially to remove a person from where political action took place. The key was to bring your Christianity to the party to make it better. You could do that as a Republican or a Democrat. But it was only in the oughts that I got such blowback. As I measured it over those years it seemed that we had a constant association with the parties as 80% Republican and 20% Democrat. The ratio didn’t change, the ardor of Republicans and their belief that it was the only party for Christians, that the Democrats were antiChristian and evil is what changed. I agree with Marsha that this is representative of most Evangelical churches.

I think Dr. Shannon’s essential point is that evangelicalism moved from the Billy Graham approach to making America better by evangelizing (making more born again Christians) to its current approach which is to get evangelical beliefs about sexual orientation and abortion as a part of the legal code of our country. His analysis hits home with me. John Fea and Kristen du Mez are two who have helped see why and how this happened.

I’m reminded of something a pastor/Bible teacher recently said to me, concerning the Christians most energized by political strife and/or culture war… “They’ve given up on the Church under the Lordship of King Jesus, as God’s primary tool for changing/redeeming the world…” (my paraphrase) Unlike the early church, which for 2-3 centuries stuck to following Jesus and thereby turned the world upside down, the religious right has abandoned that Biblical/Christocentric way and now believes that only their political power/privilege can ‘save’ things… Someday they’ll realize the profound error in this way… I just wish they’d wake up to that sooner rather than later (most likely at the exhaustion point after they’ve destroyed themselves and the lives of countless other people too…)

I thought Chris’s point Christians having to speak two languages is on the mark. I made a similar argument in a piece I wrote in January 2016 for the online magazine Aeon. Here is a taste of that piece:

“The writer Jay Nordlinger might be correct when he says that ‘all conservatives are bilingual – we have to be. (We speak liberal and conservative.) But liberals tend to be monolingual – they don’t need to speak our languages, or to know much about us at all.’ Indeed, if you are a secular progressive or liberal secularist, it is possible to live in a society that comports to your world view. If you are an evangelical Christian, it is not that easy.”

Read the piece here: https://aeon.co/ideas/is-secular-progressivism-undermining-us-democracy