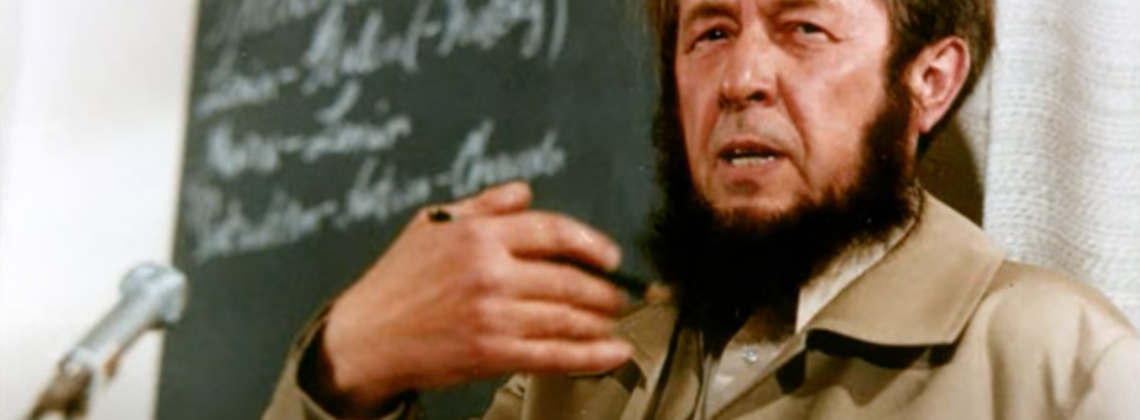

Solzhenitsyn’s truth-to-power speech still speaks

In his 1978 commencement address at Harvard University, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn told his listeners they were imprisoned. “Legally your researchers are free,” he said of the faculty, “but they are conditioned by the fashion of the day.” He accused the students of wanting nothing more than “today’s mass living habits, introduced by the revolting invasion of publicity, by TV stupor, and by intolerable music.”

More than four decades later, are American professors and students any different? Commentators on the right decry universities as lost to a “liberal agenda.” Universities across the country—especially in the aftermath of 2020, when they faced budget restrictions and potential closure—are cutting the liberal arts from their core and downsizing their faculties. They all claim to give students what they want: a chance at the American Dream. But that dream has been reduced from life and liberty to mere happiness, exhibited by their cancellation of millennia-old schools of thought. “If humanism were right in declaring that man is born to be happy,” Solzhenitsyn remarked to that restless group at Harvard, “he would not be born to die.”

Solzhenitsyn argued that the nation’s founders would never have imagined our morphed definition of freedom: “boundless freedom simply for the satisfaction of . . . whims”—what is surely not liberty but “license,” as Locke calls it. Solzhenitsyn accused Americans of living by a material superficiality that equates to the imprisonment of the mind.

The Harvard audience of 1978 was outraged that a man who had experienced Soviet internment would accuse them, the educational elite, of being prisoners. But will we heed the deeper truth of his words? Should we desire more for life than streaming media, increasing wealth and status, and posturing on TikTok?

There’s a problem in American higher education, with at least two sides to consider: the professors, who have succumbed to meaningless teaching, and the students, who have acquiesced to their culture’s low expectations of them to do little more than become money-making poseurs and civil consumers. For both parties, Solzhenitsyn demands a better definition of what it means to be a human, declaring that it is the responsibility of education to form souls with thicker substance.

When Solzhenitsyn was stripped of his role in the Soviet army, removed from his wife’s side, and sentenced to seven years in prison, he had to question all the rhetoric that he had been fed by his society. Why was Communism such a good if it had landed him in prison? What did he really believe, apart from the diet of Soviet lies, and what more permanent truths resided within him that could aid him in persevering through torture, starvation, freezing temperatures, and pointless work?

He recounts how the KGB removed everything he had thought comprised his personality—how he dressed, how he did his hair, how he enjoyed spending his time. Bald, bedecked in a prison suit, with nearly every minute scheduled by the prison guards, Solzhenitsyn questioned what of himself was left. He discovered that it was his soul. No longer would his purpose in life be fitting in with culture or amassing wealth and pleasure; there was no hope of being “happy” in the earthly sense while in prison. To keep his soul free while his body lived in chains, Solzhenitsyn composed poetry. As he recounts in The Gulag Archipelago, Solzhenitsyn saved his bread, molding bits of it into beads for a rosary. Instead of reciting prayers, he would allot lines of verse to each bead, as an aid in memorizing them. “In the camp . . . committing my verse—many of thousands of lines—to memory,” Solzhenitsyn reflects, “gave meaning to my life.”

When I teach these texts, I ask students, “What would keep you going? Where would you find meaning?” While it makes no sense according to mere scientific assessment, in the gulags those with the freest souls outlasted those with the strongest flesh.

Freedom of the soul has to do with one’s relation to the truth. A saying familiar in the Western world is, “the truth shall set you free.” When Jesus makes this claim, he does so before a group half of which wants to kill him for speaking the truth. This group executes him by the end of that story. “Violence does not and cannot exist by itself,” Solzhenitsyn writes, “it is invariably intertwined with the lie.” The truth is freeing, but it is dangerous; on the other hand, lies are easy and soothing. Before he was exiled, Solzhenitsyn admonished the Russian people, “Live not by lies!” He demanded that people be willing to lose their jobs rather than participate in lies:

As for him who lacks to the courage to defend even his own soul: let him not brag of his progressive views, boast of his status as an academician or recognized artist, a distinguished citizen or general. Let him say to himself plainly: I am cattle, I am a coward. I seek only warmth and to eat my fill.

Solzhenitsyn lived by the lesson that he taught. After his years in prison, he knew that freedom depended on living by the truth. The ones who permit the lies of our day to increase and control the narrative become less than human beings. They are those satiated by material comforts while inwardly suffering spiritual poverty.

All of us are responsible for cultivating freedom in the next generations. And so we must commit ourselves to truth. We are part of a larger story than ourselves, receiving the witness of writers such as Solzhenitsyn who produced thousands of pages “simply to ensure that it was not all forgotten, that posterity might one day come to know of it.”

In American education, as in the opening of the story in The Lord of the Rings, “some things that should not have been forgotten were lost.” Teachers of the liberal arts, in particular, are the guards of those things that ought never to have been forgotten. We’re Bilbo Baggins, writing down the story to hand to Frodo, who picks up where his elder left off. We’re Frodo, passing the book on to Samwise Gamgee. We’re like Athena in The Odyssey coming to mentor Telemachus, that he might become better than the youthful, violent suitors destroying his home. We’re Alice Walker in search of our mother’s gardens, placing memorials on the grave of Zora Neale Hurston and lifting her up before students.

Solzhenitsyn knew that even the most materially well-off persons in a culture are unhappy unless they are free. For Solzhenitsyn, prison “nourished” his soul. It taught him, more than a sermon ever could, that the “meaning of earthly existence lies not, as we have grown used to thinking, in prospering, but . . . in the development of the soul.” After Solzhenitsyn was freed, he looked back and exclaimed, “Bless you, prison, for having been in my life!”

Whether we are educators, parents, or simply those who care about the formation of the next generation of citizens, we are responsible for telling this truth and not succumbing to the lie—our contemporary lie of success.

Jessica Hooten Wilson is a Louise Cowan Scholar in Residence at the University of Dallas. She is the author of numerous books; most recently she coedited a collection of essays Solzhenitsyn and American Culture.

Jessica Hooten Wilson is the inaugural Seaver College Scholar of Liberal Arts at Pepperdine University and a Senior Fellow at the Trinity Forum. She is the author of several books, most recently The Scandal of Holiness: Renewing Your Imagination in the Company of Literary Saints.