The true, the good, and the beautiful demand closer institutional accounting

Note: The following essay was revised on January 23, 2023. An earlier version erroneously stated that Doug Wilson raised money for Thomas Achord. He did not. It also left the impression that Wilson continues to stand by the views contained in his 1996 book Southern Slavery as It Was. In fact, Wilson has since retracted the racist views in that book and released a revised edition.

*

As a strong supporter of the classical Christian school movement, I experience regular pushback from those who perceive this form of education as white, Western-only, and male-dominated. This antagonism has been amplified with the national attention drawn by Thomas Achord, the classical school headmaster who ran a white supremacist Twitter account under a pseudonym.

White supremacy has zero place in classical Christian education. It must be rooted out with the same force with which abolitionists sought to purge America of the evil of slavery. We must separate ourselves from those who knowingly support any form of racism and misogyny, while also undergoing an honest self-examination in the process. (I’m adding misogyny to the equation because white supremacy in America has a tendency to go hand in hand with the oppression of women.) If we in the classical Christian school movement want to combat accusations of racism and patriarchy, we need to consider carefully our textbooks, conference speakers, and public statements, walking the talk in the curriculum we teach, the public intellectuals we promote, and the output we produce.

When one of the authors of The Black Intellectual Tradition: Reading Freedom in Classical Literature, Dr. Angel Adams Parham, recently led a professional development for the teachers at the school I helped found, she reframed the issue for the faculty: The question is not whether we want to be a diverse school—whether we will, in her words, “sprinkle diversity” through the curriculum—but whether we will accurately tell the truth about the classical tradition and the Christian tradition that we purport in our name.

A classical school founds the education of students upon the classics, the great works throughout all of human history that deserve to be passed down from one generation to another. When choosing reading lists for students, do we ignore the works by Middle Eastern writers or Native American and African folktales? Or do we include them, as well as highlight the Ethiopians in Herodotus, read the Epic of Gilgamesh, and include the Egyptian Book of the Dead? If we are a Christian classical school, Dr. Parham cites the reality that the millennium of the Christian church was dominated by non-European thinkers, those from Alexandria, Hippo, Carthage, and so on. Twenty-first century classical educators are not adding diversity to classical Christian curriculum—we are celebrating the diversity that already exists in the tradition.

In our textbooks, we should peruse the authors of the works and, if applicable, the editors or introductory writers to ensure an assortment of voices from various nations and cultures, as well as an equality of both sexes. If we look at the table of contents of a textbook or a reading list for a semester and find not a single woman or person of color in that list, then that curriculum is misrepresenting the classical Christian tradition. If you do not know where to start, a colleague and I edited a collection of great texts titled Learning the Good Life (Zondervan 2022) that features a lineup more inclusive than I’ve seen in many anthologies.

In 2021 the Classical Learning Test revised their author bank to ensure that there is not only equal inclusion of writers across time periods but also representation from women and writers of color. Dr. Parham and I served on the committee for creating this author bank, as did Dr. Anika Prather, Dr. Jennifer Frey, and a half dozen other notable teachers and classical education leaders. I am especially excited about the number of women that we added to the Middle Ages list, including St. Hildegard of Bingen, Héloïse d’Argenteuil, Marie de France, St. Catherine of Siena, and Christine de Pizan. Classical schools should look through their reading lists to make sure women and persons of color are not excluded from their curriculum.

When these groups gather, they should be lifting up more than the white men in their ranks as wonderful speakers and teachers. Side by side with these leaders should be women and writers of color. In 2021 I was impressed that the Classical Learning Test called a Higher Education Summit that included these headliners: Cornel West, Robert P. George, Anika Prather, Spencer Klavan, Christopher Perrin, Jennifer Frey, and myself. Likewise, the Society of Classical Learning has promoted speakers from a variety of backgrounds, and these organizations seek to represent the best in classical education. I should also mention the recent event held at Baylor University in which all of the keynote speakers were African American: “Classics and Classical Education in the Black Community.” Hundreds of schools across the country are looking to these events to come to know the leaders who can develop their faculty, the writers to recommend to their parents, and the talks to share with their students. If the classical Christian school movement does not want to unintentionally deform its participants, we should be careful about the models we present for imitation.

Finally, the classical Christian school movement promotes this education through books, online journals, social media accounts, and podcasts. What ideals are we collectively showing the world through our witness? From my experience most of the teachers in the classical school movement are women, but from listening to podcasts or reading on classical education, you would assume the majority of practitioners are men. Again, these discrepancies appear most clearly in a table of contents page or a list of guests on a podcast lineup. The Classical Academic Press stands out as a press that attempts an equality of perspectives with its representation. As classical Christian organizations consider to whom they give platforms and whom they interview and publish, they should be intentional about rejecting fallacious proponents and reaching beyond their close circle of friends to extend invitations to those who are doing good work and have much wisdom to share.

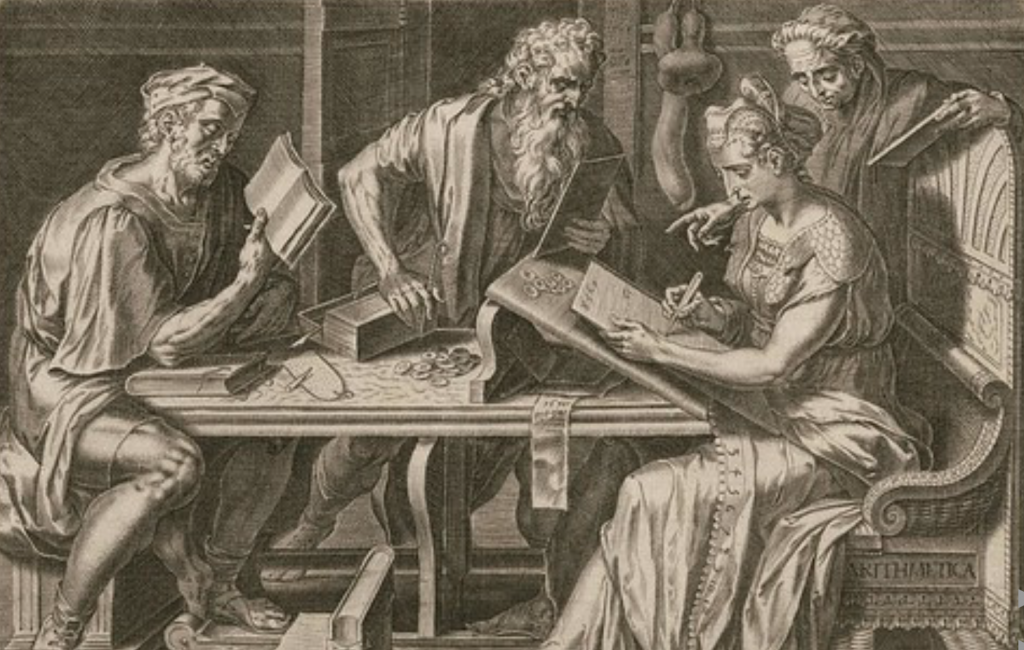

Within the classical Christian school movement we have seen decades of young people fall in love with learning, coming to reason and discern well, and to practice civil discourse and the virtues of hospitality and charity. This movement tries to revitalize the tradition that has been lost: not merely content (those great books so often mischaracterized but worthy of admiration) but also the liberal arts, including the trivium of grammar, logic, rhetoric and the quadrivium of the numerical arts. If the classical Christian school movement is to survive—let alone flourish—we must oppose current manifestations of racism and misogyny and stand with the beauty, goodness, and truth that we hold up for our students.

Jessica Hooten Wilson is the inaugural Seaver College Scholar of Liberal Arts at Pepperdine University and a Senior Fellow at the Trinity Forum. She is the author of several books, most recently The Scandal of Holiness: Renewing Your Imagination in the Company of Literary Saints.

I am grateful that this article points us to reading lists, speakers, and conferences for where to go to for growth and best practice.