Which side is really telling The Big Lie? There’s only one way to find out.

Most high school and college teachers have more than once encountered a student who refuses to accept criticism on the grounds that the essay he turned in really is his essay and not someone else’s. How could the teacher possibly be in a position to suggest it is not his own work? The teacher politely responds that she knows the student is honest and has not plagiarized. But even though the statements in question are his, the teacher continues, they also happen to be false. “How could they be false?!” exclaims the exasperated student. “I know what I think and have truthfully reported it. Since you are not a mind reader, you are in no position to say the claims are false. I really do believe them. That is why I put them on paper.”

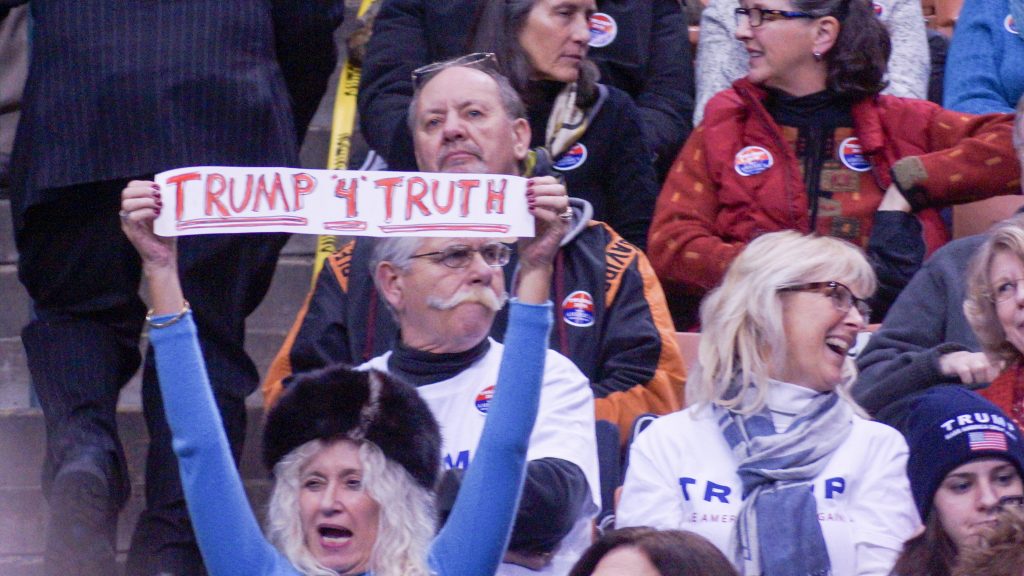

Episodes like this help to explain the perilous condition of our public discourse. Increasing numbers of Americans have come to confuse sincerity and accuracy. They have come to believe that speaking the truth just means being honest or sincere. If I really believe, for example, that Trump won the 2020 election by a landslide and I register that belief honestly, I am speaking the truth. Never mind whether Trump actually won the election; never mind whether my claim is accurate. The test of truth involves only an internal fit between my actual beliefs and my own report of them, not a fit between what I believe and what is really the case.

Almost twenty years ago the late British philosopher Bernard Williams published a book entitled Truth and Truthfulness that ought to be required reading for all students at colleges and universities. In it, Williams gives a genealogical account of how we have come to confuse or elide sincerity and accuracy. This confusion began during the Romantic period, a kind of precursor to modernity according to some intellectual historians, when there arose a cult of sincerity. The virtue of sincerity was thought to be a premier virtue in that it rendered visible the interiority of the new individualism in a publicly reliable way. And sincerity easily kept company with its conceptual cousin, authenticity. Authenticity involves the discovery and elevation of a “true self” underneath all of the cultural costumes that we wear. And the expression of that self truly requires, of course, the virtue of sincerity.

All of this is as historically instructive as it is politically corrosive. Truth as sincerity is the oxygen of authoritarian regimes. Once I am obsessed with sincerity as the only criterion of truth, I must search for someone who speaks with authority, whose sincere claims are thus authorized. I do not need to worry about accuracy, since authority legitimizes accuracy, rather than the other way around. I am, in short, looking for a messiah, for one who “speaks with authority.” And as long as I am satisfied that my messiah is being sincere, as long as I believe that he is “speaking his mind,” I can then follow what is true. No wonder so many of Trump’s followers regard him as a divine figure.

Once this whole confusion between sincerity and accuracy is understood, many otherwise obscure or puzzling features of our recent political landscape are suddenly illuminated. If evidence establishes accuracy, repetition establishes sincerity. Thus, the “big lie,” the repeated claims that Biden stole the election and that Trump won it by a landslide, could never be established through evidence, the lifeblood of accuracy, but only through endless repetition, the lifeblood of sincerity. Lest our faith in our messiah waver, Trump repeated the same claims over and over every day after the election and has now made it a test of Republican loyalty to him From the vantage point of those concerned with truth as accuracy (as established by evidence), this is of course a picture of authoritarianism. But from the vantage point of those concerned only with truth as sincerity, this is a picture of a truthful man victimized by various conspiracies.

Almost all of Trump’s followers explain why they admire him by saying, “He says what is on him mind.” He is a “straight shooter.” You can “believe him.” Well, yes, you can believe that what he says is really what is on his mind. But you cannot believe that it is true unless you also believe that truth is simply sincerity. For perhaps most of our history, we thought that before we praised someone for saying what he pleased we ought to consider what it pleases him to say (to paraphrase Burke). But this sound conservative counsel has become lost to many Americans and to perhaps a majority of so-called conservatives.

How did this happen? I think we are better advised to rely upon Bernard Williams’ genealogy that goes back to the Romantic period rather than blaming the loss of faith in truth-as-accuracy on postmodernism and the academy. Many have insisted that the tendency of academics to put the word “truth” in scare quotes—evidence, these scholars think, of their sophisticated understanding of how social and cultural situations always shape our perceptions—has led to our present confusion over truth. And there have been, to be sure, a lot of lazy but fashionable thinkers who have repeated the Foucauldian claim that all truth finally reduces to power. Many have done this because it spares them the hard and difficult task of dealing with the recalcitrant evidence against their own political positions.

But the academy is not responsible for our contemporary degradation of the truth. Those who claim that it is are parochial: They seem to believe that the entire university is the Cultural Studies and English Departments writ large. But universities also have professional colleges, and departments like Physics, Mathematics, Chemistry, and Biology for which the idea of truth in quotes is ludicrous. Blaming the academy or leftist intellectuals for our present predicament is misguided. We should look instead to the social and economic roots of an authoritarianism that depends upon and promotes the idea of truth as sincerity.

We should look as well to many of those who did, on both the political right and the left, show little regard for telling the truth and a lot of regard for maintaining their own positions of power. Sadly for our republic, those who secure their power by being dishonest damage irreparably both the virtue of sincerity and the virtue of accuracy. And worse still, they make it more and more difficult for all of us to distinguish between the two: Trumping truth.

Mark Schwehn is Senior Research Professor in Christ College, the honors college of Valparaiso University, and editor of the second edition of Leading Lives That Matter: What We Should Do and Who We Should Be.

Mark Schwehn is Senior Research Professor in Christ College, the honors college of Valparaiso University, and editor of the second edition of Leading Lives That Matter: What We Should Do and Who We Should Be.