In her new novel, Jamie Quatro turns against facsimile for the sake of reality itself

Two-Step Devil by Jamie Quatro. Grove, 2024. 288 pp., $27.00

I’m thinking of Marcel Duchamp’s 1912 painting, Nude Descending a Staircase, No.2, which hangs in Philadelphia, in the museum known best for its Odessa-esque staircase over which Rocky (the boxer) triumphs. Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 presents no obvious nude—at least not what typically comes to mind when we think of “nude” and great art. Works by Michelangelo and Manet’s The Luncheon on the Grass, for example. Realistic representations of unclothed human bodies, studies of skin folds and hair, sinew and musculature. Real bodies, real enough, at least, such that the way we speak of them is, “a naked lady on a picnic blanket” and not “a painting of a naked lady on a picnic blanket.”

Let the record show that there is no discernable staircase in Duchamp’s painting, either.

Instead, the entire work is a mighty collection of boldly executed angles and triangles, some repetitions of one another, near-circles and slashes, all jammed together and rendered in flesh tones that fade into shadows in the upper-right and lower-left corners. Our attention is called to the fact that we’re looking at a painting, an imaginative depiction of a worldly experience rendered in paint, on a two-dimensional canvas—not an attempt to convincingly imitate what it might literally look like if we were to see a naked person walking down some steps. All we’re left with is “descending.”

Movement, then, is the painting’s only apparent certainty. A worthy and unexplored artistic subject matter, freed from the staid conventions of the day because of the fresh conventions by which Duchamp created and ordered his work.

And now I’m thinking about Jamie Quatro’s novel Two-Step Devil and about how literary works that depict children in peril are fairly common. Kingsolver’s 2023 Pulitzer Prize winner Demon Copperhead, Charles Dickens’ David Copperfield (Kingsolver’s source material) and even The Boxcar Children. While I confess I can’t recall the exact circumstances of their lives, they were, in the end, children who lived alone in a boxcar.

Such books are usually hyper-sincere, every seam and joint of the narration totally obfuscated. The author holds our hands through a house of horrors, inviting us to look at the monsters from a protected path. The monsters prey upon their designated underage victims and we’re sheltered by the author for the entire experience. We see, but we are not a part of. The endings are typically iron-clad (“The kid wins!” or “Everybody dies!”) and we close the book and wonder, from the safety of an easy chair, how the world has come to this.

But good writing imperils the readers’ sensibilities. And good authors dare not only to put their characters in danger but their readers’ sightlines as well. Quatro, always a daring writer, does all this and more in Two-Step Devil. Her whole way of looking gives us pause.

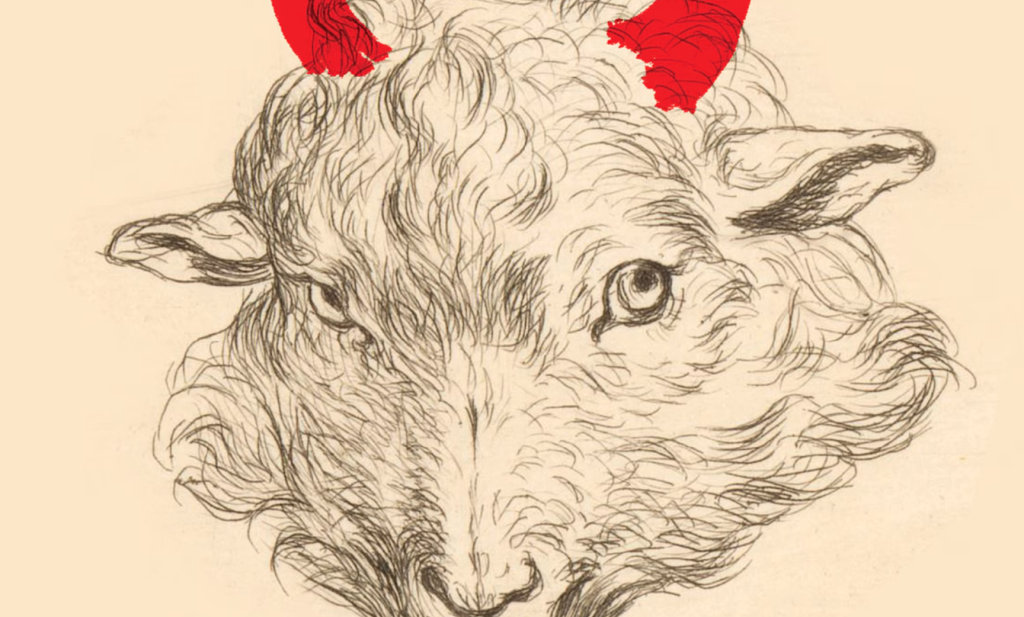

“Pause” is wrong. Full-stop is more like it. A conventional-sounding summary of Two-Step Devil might be: A teen girl is kidnapped from sex traffickers by a spooky old man who thinks God told him to nab her because she’s the Chosen One and her job (he thinks) is to enact the bizarre delusions that God revealed to him.

Ha.

Quatro changes points of view, flashes back, writes in poetry—perhaps prose poetry—and delivers a historical travelogue of Chattanooga, Tennessee and environs. All at the same time. Aside from the prologue and the epilogue, the book is divided into four parts: “Prophecy,” narrated in the third person, close-in to Quatro’s main character, The Prophet (the aforementioned old man to whom God gives visions). Next, “Song of Songs,” narrated in the first person by Michael, a teen girl, the child in peril. “Gospel” is the shortest, written in the form of a script of a play. Finally, “Revelation”: a series of writerly bursts—some of them mini-poetic soliloquies, while others are scenes in the third-person present tense, packed with tension.

While the entire book is compelling, “Gospel,” the section written in script form, is most compelling of all. In it The Prophet and the devil, the titular Two-Step Devil (“two-step” because he appears in the form of a dancing cowboy) face off. The Prophet, sometimes costumed as Jesus and sometimes in the sludgy contours of humanity, is run through a mill of tribulations at the devil’s hand. But as Quatro delivers the story we become acutely aware that it isn’t real. Our attention is drawn to the form. A script in relation to a play, most especially a play that seeks to mimic reality as best it can, given the limitations of a stage, is the one part of the entire production that can’t hide behind a veneer of reality. The words the actors say—for that is Kenneth Branagh up there, not actually Richard III—and where they stand and what all they do is entirely preconceived. A script, then, is hard evidence of unreality. The needle for the balloon. But a written script that doesn’t refer to any actual play—i.e. the “Gospel” section of Two-Step Devil—is hard evidence of an unreality disconnected infinitely further from life as we actually experience it.

Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2 was first exhibited in the United States at the Armory Show in 1913. Predictably, everybody hated it (which must’ve thrilled Duchamp. Don’t forget, five years on, he’d sign a urinal “R. Mutt” and display it as a sculpture entitled Fountain). I dare say that what the art-going public actually hated was the affront to their limited notions of art and what it should do out there in—and for—the world. Quatro writes into a numbed culture that has lost the ability, for the most part, to even feel offended when the artists and writers—as they should—chafe against the forms in which they work. And this is because we’ve relegated good art to the “extra-credit but totally optional” page of life’s syllabus.

But let’s dare our senses to move, along with Quatro’s, against the cultural tide. With Two-Step Devil, Quatro renders a world with the colors of reality, but around, above, and below our ability to perceive it as such. What can this do for the subject matter—a young girl abused, a sick old man with Godly visions, and a world that needs them? Artistic facsimiles have all been made, and they’ve all been made for a long time now. But via Duchamp’s painting, we know that which is ever living inside a temporal moment. What is new, new all the time, what Quatro gives us daringly and masterfully in Two-Step Devil, are the vantage points.

Paul Luikart is the author of several short story collections , including The Realm of the Dog. He serves as an adjunct professor of fiction writing at Covenant College in Lookout Mountain, Georgia and lives in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

Great review. What a stunning book.