Perhaps it’s time to reconsider the Promise of America

Hope is an uncommon, even strange national virtue. Strange, that is, unless the nation in question is the USA. Americans have always been a forward-looking, optimistic people, self-assured in our actions and confident in the power and pathways of our own virtue. Born amid an Enlightenment-based high-water mark for the idea of human progress, Americans always placed hope at the center of our vision of ourselves and our place in the world.

Our buoyant account of hope has come alongside the presumption of a higher calling. We are the land of the free. The home of the brave. God shed His grace on thee. We are the first new nation “conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” In overcoming our failures and striving toward our better selves, Lincoln famously dubbed America the “last best hope of earth.”

As the twentieth century dawned, we leaned into the name given to the statue gifted us by France and planted in New York Harbor: Liberty Enlightening the World. Cries the lady with the flame:

Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!

A nation of nations. A friend to the friendless. A land of opportunity. A melting pot.

When we weren’t opening wide our doors to the world’s oppressed, we were storming the gates of Hell “making the world safe for democracy.” At his 1961 inauguration, John F. Kennedy poetically proclaimed, “Let every nation know, whether it wish us well or ill, that we shall pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship, support any friend, oppose any foe to assure the survival and the success of liberty.”

I have always rested somewhat smugly in the notion that I was immune to these overwrought visions of hope in America. As a professional historian and college teacher, I’ve logged hundreds—probably thousands—of hours exploring and explaining the yawning gap between the starry-eyed rhetoric of an idealized America and the mundane, often brutal realities of the same. Scandals, duplicities, failures, shameful hypocrisies, and notable blunders litter the American story. Enslavement, Native extermination, land expropriation, fleecing the poor, sexism, Chinese exclusion, Jim Crow violence, and varied war crimes, I thought, provided sufficient evidence to ground me in a sturdy realism about my country. Land of Hope? Not exactly.

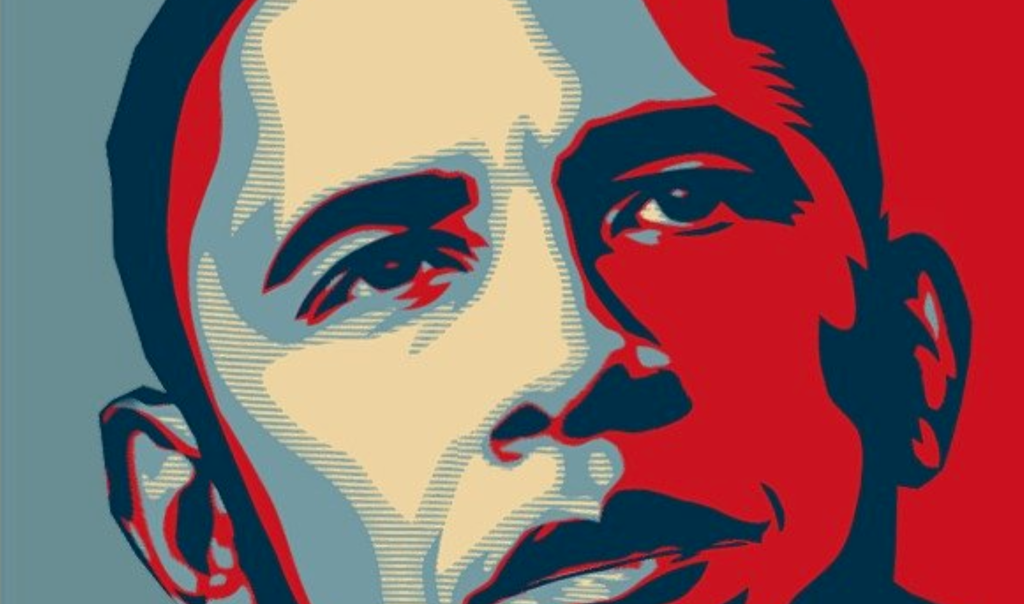

And then . . . 2016 happened. Among the multiple ways the first Trump election landed a punch to my face was its revelation of how deeply I did care about the great American experiment. Not only did I care about it, I believed in it. The democratic act of handing this self-indulgent, willfully ignorant, profanely amoral bully control over the American project shook me to the core. As we listened to election news the morning after, my wife and I sat and wept.

What did those tears mean? What was their source? After eight long years of reflection—and a second Trump election—I think I am starting to understand. Our tears flowed from our own deep well of hope in America, little different from that expressed in the transcendental language of Lincoln, Lazarus, Wilson, and Kennedy. I experienced the election as a betrayal of something foundational in my life. Without realizing it, the affections of my heart—even my psychological well-being—rested on the abiding promise of the American project. Despite all evidence to the contrary, I had managed to retain the presumption of a stable, virtuous and, yes, eternal America. Flawed? Indeed. Prone to hypocrisy? No doubt. But, in the end, enduring, exceptional, and ultimately good.

As we stand at the dawn of a second Trump administration, my thoughts have been fixed on my own complicated relationship with this hope. The profound gift of the 2016 and 2024 elections to me has been their sober reminders of the fleeting impermanence—and meaninglessness—of all things under the sun. The small, ultimately inconsequential nature of things when viewed in the light of eternity. “Behold,” observed the prophet Isaiah, “the nations are like a drop from a bucket, and are accounted as the dust on the scales.”

I care about America’s institutions, the rule of law, the plight of the world’s weak and oppressed, and the principles of decency, justice, equality, and liberty. I remain concerned about the health of our republic with someone of Trump’s character piloting the ship. But I take strange solace in the words delivered by the Old Testament patron of suffering, Job, to his well-meaning but clueless friends: God “makes nations great, and destroys them; he enlarges nations, and disperses them. He deprives the leaders of the earth of their reason; he makes them wander in a trackless waste. They grope in darkness with no light; he makes them stagger like drunkards.”

I have spent my life attending churches that regularly sing the following familiar lines: “My hope is built on nothing less / than Jesus’ blood and righteousness. / I dare not trust the sweetest frame / But wholly lean on Jesus’ name.” While I have always belted out these stanzas with conviction, I now see that they probably weren’t true for me. Another powerful, unexpressed hope also has gripped my heart. My resolution for this new year is to believe these words, and to do so, in part, by learning to read developments in the news cycle and their fate through an infinitely wider lens that places them in their proper perspective. All other ground is sinking sand.

Jay Green is Professor of History at Covenant College. His books include Christian Historiography: Five Rival Versions and Confessing History: Explorations of Christian Faith and the Historian’s Vocation (edited with John Fea and Eric Miller). He is Senior Editor of Current.

One wonders not merely about the American experiment, but about the church. My struggle is not only with the American experiment gone wrong, but with a church that’s supports the direction of the U.S. It is the loss not of merely one home, but two.

Wow, I can really relate to this. My experience almost exactly, trying to juggle feelings about the entire American experiment, mesh them with my theological perspective which puts–or should put–those feelings in a very subordinate place, and all that in the context of the day-to-day (and even hour-by-hour sometimes) events of politics and society. It’s a time of testing, and I’m not sure what grade I got/will get.

I confess I’m glad not to be teaching anymore: during the first administration, try as much as I did, I apparently couldn’t keep a certain bitterness and maybe even cynicism from creeping into my soul. I never actually indulged it, as far as I know, certainly not intentionally, but it was there, and students noticed–which made me feel guilty: they have a right to come to their own sense of these things, and not have one imposed on them by some old man with a very different set of experiences.

I might have a quibble–not sure–with this:

“The profound gift of the 2016 and 2024 elections to me has been their sober reminders of the fleeting impermanence—and meaninglessness—of all things under the sun.”

Impermanence, yes. Meaninglessness? Not sure. As that familiar verse says, “God so loved the world …” The world he loves is this very world, not some ideal world–the impermanent world of shifting sands and compromise and cowardice and venality and all the rest, and while it may be meaningless when regarded as itself, my suspicion is that that love transforms all things and renders them infinitely meaningful. That I’m unable, at times, to see it or feel the same towards it isn’t the world’s fault, it’s mine. The fact that God considers it worthy of His sacrifice–that it’s worthy as it is–challenges me to cease demanding that the world be something I approve of before I love it too–and that means loving it with the America we have, Trump and all.

My husband and I can relate to this as well, he comes from a military family and is highly patriotic. When Trump was elected a second time, he carefully folded up our flag and said he wouldn’t be displaying it. It is a real sadness that we feel, yet our church home and our faith has been our anchor for these times.

“I have seen all the things that are done under the sun; all of them are meaningless, a chasing after the wind.” -Ecclesiastes 1:14

How we take Ecclesiastes is a fascinating interpretive question. I’m convinced by those who say that it’s a record of a very wise someone’s conclusions, drawn from an observation of the world as it is without Christ, or even the Old Testament’s anticipations of Christ.

I certainly seems clear Christians can’t take its pronouncements of meaninglessness in any maximalist sense. “Things done under the sun”would include, eg, the preaching of the gospel, which Paul tells us has great meaning. The angels rejoice over a sinner’s repentance–another thing done under the sun. Acts of mercy and love, likewise. So, those are all sacred things, we could say, but what about the mundane? Art, politics, medicine, and so forth?

The theology here is above my pay-grade, but I’d be interested in reading more thoughts about it, especially from good theologians unpacking the significance of the incarnation for such matters. But even short of that, we could also look at what Isaiah says about Cyrus, and Paul about the emperor, and ask whether these writers agree with Ecclesiastes on this question.

Maybe what you’re saying–and what the latest poltical disasters are teaching us–is to respect that last clause in the injunction from the prophet Micah. We want to be doing justice and loving mercy–we still can, even if we are not getting public endorsement of our projects to do these things. I tend to get fired up with righteous energy for what I think will bring justice and mercy while forgetting that last clause about walking humbly with God.

This is a beautiful and heartfelt, sane piece (I say “sane” because we are faced with so much seeming insanity these days). I very much relate, but I think the greater pain I feel is what I have seen happen to the church. My hope cannot be in America (as much as the American project promised very good things it has been steeped in genocide and the denial of these good things to Black Americans) but I had hoped that American Christians could see the darkness of what is happening. But darkness is now so often being called light. THIS is what pains me, confuses me, breaks my heart, and so much stress. Reading Matthew 23 A LOT has been helpful. It’s helpful to see that this clinging to an “empire mentality” (Brueggemann) for the sake of increased power and comfort is nothing new. But it is so ingrained in the history and comfort level of the white church in America. I think we could all learn so much from the Black church–feeling gaslit, confused, and abused by those who claim Christ is, sadly, nothing new for them.

Well said, Ellen.