What YouTube’s rolling out we may actually need!

A recent Washington Post editorial declared YouTube “the most consequential technology in America.” And it did so convincingly. In addition to being the place we go for tutorials on how to replace a car battery, participate in group exercise, and receive tips on pickling red onions, tech columnist Shira Ovide notes that YouTube is the number one site for all video watching (sorry Netflix), music/podcast listening (no contest, Spotify), and social media collaboration (not even close, TikTok). YouTube is king, by miles and miles.

The ubiquitous video-sharing application is nearing its twentieth birthday, and more Americans spend more hours on it than any other. Ovide calls it the “healthiest economy on the internet,” within which thousands of producers (err, “influencers”) have found unimagined fame and fortune. It has also become the latest source for feeding the next frontier in our digital revolution, as the trillions of words contained within it are now being fed into every imaginable version of the emerging wave of AI large language models.

Like most people, I have wasted many hours on YouTube since it launched in 2005. While it is now many different things to its countless users, I first experienced it as an almost mystical time machine through which I traveled to regions of my childhood I never expected to see again. I’m reminded of an arresting scene from the AMC series Mad Men in which ad guru Don Draper pitches a campaign to some Kodak executives for a newly developed wheel-based slide projector. Despite the timeless appeal of the “new,” he observes that ads generate even “deeper bonds” with consumers by accessing feelings of nostalgia. A friend once told him

that in Greek nostalgia literally means “the pain from an old wound.” It’s a twinge in your heart, far more powerful than memory alone.

This device isn’t a space ship. It’s a time machine. It goes backwards, forwards. Takes us to a place where we ache to go again.

It’s not called “The Wheel.” It’s called “The Carousel.”

It lets us travel the way a child travels: around and around and back home again to a place where we know we are loved.

YouTube endures as a portal that can “take us back to a place where we ache to go again.” A time machine. A nostalgia factory. My first month on the site was spent doing little more than finding and reexperiencing video segments from the early days of Sesame Street and The Electric Company. My thirty-five-year-old self instantly journeyed back to the early 1970s: I’m sitting in my pajamas watching TV as my mother folds clothes and makes my breakfast. Access to such content is so commonplace today that it barely warrants notice, but our earliest access to these forgotten images spawned feelings and memories that were nothing short of magical.

I’ve spent the past several months working on a project that immersed me in the 1970s, a decade famous for all kinds of social, economic, and political “malaise.” Declining confidence in institutions, cynicism in politics, record crime rates, “stagflation,” crumbling cities, and high anxiety that America’s best days were in the past led a 1979 Time editorial to state that no one was ever going “to look back on the 1970s as the good old days.” For all its confidence, the editorial could not have been more wrong.

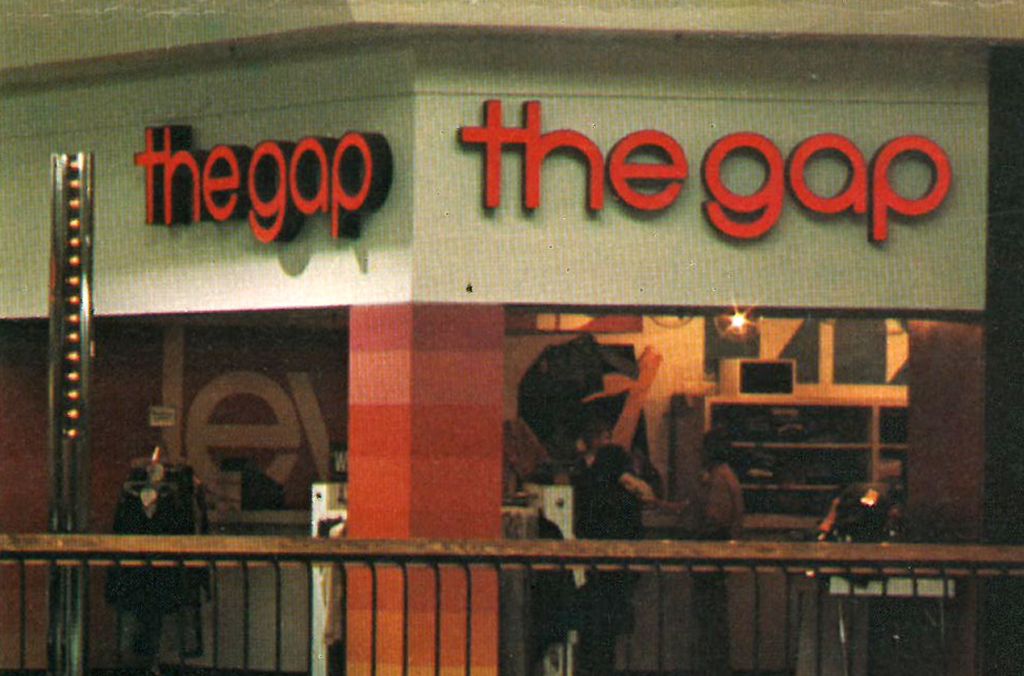

While there are thousands of ways to “get back” to one’s childhood on YouTube, my favorite is a glorious sub-sub-sub-genre that features raw videos, sans commentary, of ordinary places filled with ordinary people doing ordinary things in the recent and distant past. A street corner at 5:00 pm in 1961 Chicago. High school students from 1993 in suburban Los Angeles waiting for the day to begin. And one that recently caught my attention: shoppers in 1978 milling around the (now dead) Pyramid Mall in Plattsburg, New York.

Nothing happens in the video, and, primarily for that reason, viewers become transfixed by all that magnificent nothingness. We wander with the camera along the mall’s darkly lit corridor—the heavily stained wood trim accented by hues of harvest gold and avocado green. Shoppers bedecked in polyester pants and satin jackets while teems of clerks ring up orders on gigantic cash registers. Tank-topped preteen boys watch their friends play pinball and foosball at “Fun Land.” Older men wearing hats and neckties follow their wives about looking for bargains. The ever-present sound of fake waterfalls running over fake rock formations, can be heard in the atrium as other shoppers pass by the Hallmark Store, the Music Manor, and Hickory Farms.

What strikes me most on this page are the comments. No one traveling in this time machine laments 1978’s double-digit inflation, Cold War anxieties, or high crime rates. Every last comment is filled with loss and longing for a better time. “Thank god I lived my childhood with no cell phone in hand.” This was a “time when people had good common sense!” “Back then people respected one another, dressed well and behaved.” “These poor people had no idea back then of the nonsense world that would come in the 2020s.” “Life used to be so good. I feel bad for young people.”

I reacted at first to these comments with a cynical eyeroll. My historian brain is well acquainted with the harmful distortions, selective remembering, and cheerful wishcasting of nostalgia. A commitment to busting myths and tarnishing golden ages was part of the solemn oath I took upon receiving my union card as a practicing historian. I mean, c’mon! The 1970s were filled with millions of unhappy, anxious, angry Americans pining for “Happy Days” past.

But another part of me—my heart, probably—paused to give those comments another glance. Perhaps the wistful observations of the Pyramid Mall from 1978 are best read not as ham-handed efforts to interpret the “real” 1970s but as primal screams from an anxious and turbulent present bedeviled by a fast-changing world that often feels like it’s hurtling out of control. Our hearts all long for home—a place where our mothers make us breakfast while we hang out with Grover and Kermit. All of us need reminders of a better country where things are as they should be, of places “where we know we are loved.” If we can gain even a small taste of that while strolling through YouTube’s Pyramid Mall, so be it.

In the meantime, if anyone asks, I’ll be down at the Orange Julius watching The Adventures of Letterman.

Jay Green is Professor of History at Covenant College. His books include Christian Historiography: Five Rival Versions and Confessing History: Explorations of Christian Faith and the Historian’s Vocation (edited with John Fea and Eric Miller). He is Managing Editor of Current.

Oh, yeah, Jay – I remember the seventies as my spiritual coming of age in so many ways. For me as a Christian, a reasonable nostalgia (i.e. not a “golden-age-we-were-so-much-better-than-we-are-today”) reminds me that God is faithful, good, and always in control. Reasonable nostalgia also includes recognizing the fears I had at that time that proved to be just that – fear of the unknown. Part of nostalgia’s appeal for me, at least, is that the past (as distinguished from history) cannot do us any harm.

My nostagia also includes the time when I had the best conversations with you about how to generate interest in a secondary school counterpart to CFH about 15 years ago when I was teaching at Community Christian School here in Melbourne, Florida.