What are you listening to this December?

As usual, I have been listening to a highly eclectic list of music, because I am a total musical weirdo. Ask me what kind of music I like, and I’ll have no answer for you, because I’ll be listening to Robert Burns’ “Caledonia” on alternating repeat with “The Pirates Who Don’t Do Anything” and there’s really no way to describe that through genre or adjective. Unfortunately for any effort at synthesis, my preferred Christmas music is characterized by the same randomness: currently playing this December are the Tudor carol “Nowell Sing We,” the gorgeous German hymn “Maria Walks Amid the Thorn,” and, I’m embarrassed to admit, “Scrooge,” from the Muppet Christmas Carol movie.

To be brutally honest, it’s not just “Scrooge” from the Muppets movie, though. It’s worse than that. It’s a cover of “Scrooge” sung by a shanty band.

So now you know who I truly am. I’m a bespectacled homeschooling historian-mom who listens to shanty band covers of puppet songs.

I’ve spent a fair bit of time this week thinking through why I (and my whole family) enjoy this song so much. The band, The Longest Johns, is already one of our favorites, both for its musical quality and for its delightful performances. The Longest Johns convey a wide range of emotions in their music with flexibility, creativity, and sincerity and I’ve never met a song of theirs that I didn’t like. I daresay they convey the thrust of this particular song – a chorus of criticism of that infamous yuletide miser, Ebeneezer Scrooge – even better than do the original muppets. The Longest Johns go all-in in every possible way in the music video, even dressing up as “mouses” when required. One poor fellow even pretends to be an ear of corn.

So of course we love the Longest Johns’ version. It’s just so much fun.

Fun is not the whole reason that this song is such a good one, however. There’s also the moral aspect of the words. Yes, it’s meant to be humorous, but it’s also an example of a chorus offering moral commentary, even judgment of a particular character as part of the exposition in a larger story. Here, the chorus is used to tell us who Scrooge is, and in doing so, the song also reflects on the values held by the community.

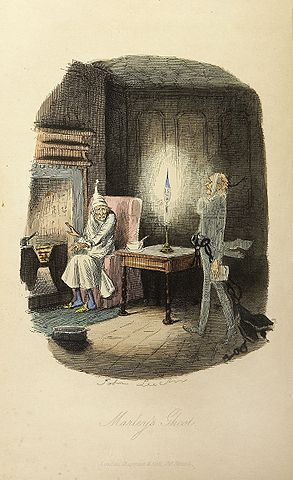

What values do this community of men, muppets, mice, and vegetables share? The song suggests that they believe in fair dealing, friendship, conviviality, and charity more generally. The singers range from bonneted middle-class church ladies to ragged street urchins, but they are united in their befuddlement over Scrooge’s grim, humbug behavior. Charles Dickens’ original tale boasts a cast of characters who hold similar beliefs at Christmastime, or at least attempt to do so; from Scrooge’s cheerful nephew to the desperately poor and threatened Crachit family, nearly all the supporting characters are oriented toward community, kindness, and celebration at this time of year. In order to judge Scrooge as grim, the chorus must value joy.

Therein lies the attraction of this particular version of “Scrooge.” The Longest Johns are adept at conveying the whole range of emotions present in sea chanties and other work songs and elemental types of folk music. Although of course they aren’t foremast Jacks themselves, as far as I know (I think a few bandmembers used to work in tech?), they connect with and understand both the gaiety and the morosity of this type of music. When they bring this to a song like “Scrooge,” we really believe that they believe what they are singing. Indeed, they clearly relish it. They convincingly suggest that is it possible for a whole, wide community of people to believe in and practice good things together. Thus, a shanty band singing about Scrooge reminds us, however surprisingly, of the things in which a community ought to believe at Christmastime: fair dealing, friendship, conviviality, and charity more generally.

Of course, 19th-century London was not a place that rang out with such values. The original novella and the song both offer strong social criticism about what is lacking in that context and, by extension, in our present-day one. But it also calls us to something better. When we listen to this song, we think: Wouldn’t it be wonderful to live in a community whose belief in good things was so strong that we could accurately identify those who were working against them? Shared judgment can ruthlessly damn the innocent at times, but it also can help uphold charity. It seems as though, at Christmastime at the very least, we ought to be able to share a belief in both celebrating and giving celebration to others. We ought to be able to treat each other as if Christ were indeed born this day. For He is!

It’s a surprisingly hard thing to do, however, and an even harder thing to believe. It’s a good thing, then, that we have shanty bands dressed up like “meeces” to help us along the way.