An anti-Trump conservative makes his case—and his plea

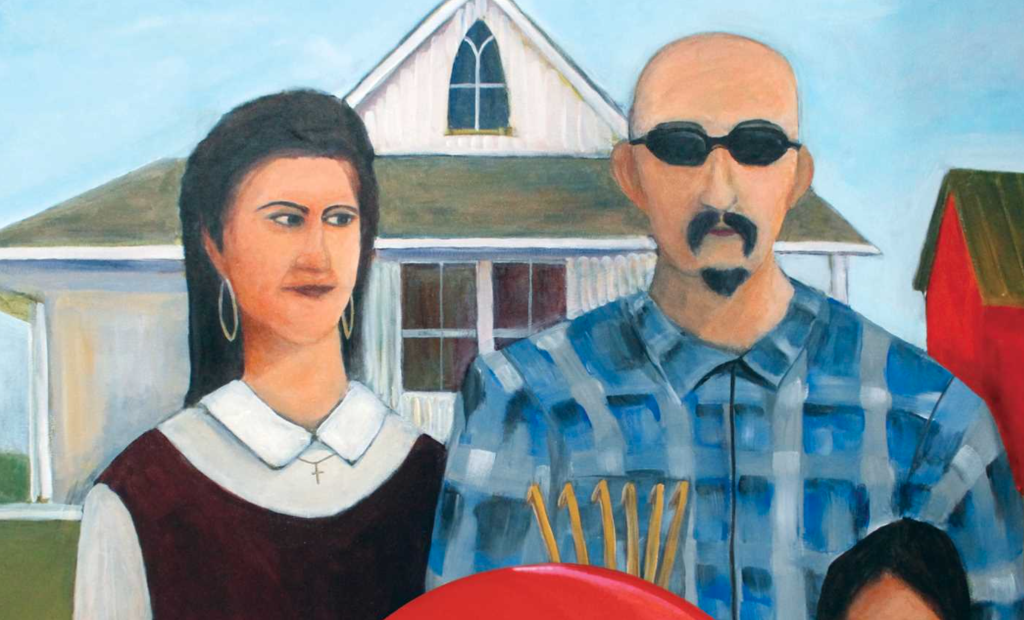

The Latino Century: How America’s Largest Minority is Transforming Democracy by Mike Madrid. Simon & Schuster, 2024. 272 pp., $28.99.

Mike Madrid’s The Latino Century is a new book with a familiar refrain: Politicians have been taking Hispanic Americans and the Latino vote for granted for much too long. In an election as dramatic as 2024 is shaping to be, this is a mistake.

While many see Latinos as a monolithic entity, Madrid insists that the diverse multiracial identity of Latinos and other Americans is poised to change the American socio-political landscape. The problem: The two major political parties have not figured this out yet. This evolving scenario is what gives Madrid hope for America’s future. In the meanwhile, however, he is concerned that democracy is under attack both globally and at home. He writes, “Both of our political parties have devolved into tribes, viewing themselves as the saviors of their respective views of democracy and members of the other tribes as an existential threat to the country.” How did things get this bad?

At the heart of Madrid’s book is his juxtaposition of Ronald Reagan and George W. Bush (his heroes) and Donald Trump (someone Madrid deems to be lacking in character). He declares that “Trumpism emerged with the collapse of Reaganism.” Madrid originally became a Latino Republican based on Reagan’s confidence in U.S. values during the closing decade of the Cold War. He claims that subsequent presidents squandered an opportunity to spread democracy. Now the Republican party of Madrid’s youth has been taken over by an alien force.

But perhaps Trump-like elements have been there all along—especially the vitriolic anti-immigrant element. There is, though, a crucial difference: Savvy politicians like Bush deliberately and thoughtfully courted the Latino vote. For Madrid, Bush was the first candidate and president to center events around recruiting Latinos to the party in an authentic, non-patronizing way. For his efforts, Bush won over forty percent of the Latino vote in 2004, the highest ever for a Republican presidential candidate. “George W.’s optimism, like Reagan’s, was a perfect fit for the optimism of Latino voters.” The stark contrast between the optimism of Madrid’s political heroes and the current GOP couldn’t be clearer. So what can be done? Madrid has spent decades now working behind the scenes, and the book details those efforts.

Madrid tells about his experiences collaborating with the Democratic politician Antonio Villaraigosa, who served as mayor of Los Angeles from 2005 to 2013. Madrid’s decision to collaborate across party lines foreshadows his more recent work in the Lincoln Project. He has been looking for aspirational political voices that are also pro-immigrant, and Villaraigosa fit the bill. Madrid respects Villaraigosa enough without agreeing with him on everything. He sees their collaboration as a way to challenge policies from elements of both parties that he finds harmful. Madrid sees his more recent work on the Lincoln Project, created to challenge President Trump, in a similar light—a way to challenge harmful policies within the party that was once a welcoming political home for him and other Latino voters. With the current election only weeks away, one wonders what influence Madrid and his associates will have this time around.

But while Madrid is concerned with the Republican Party’s present lack of deliberate interest in attracting the Latino vote, the contemporary Democratic Party’s approach to courting the Latino vote has not been much better, in his estimation. How does one explain that Latinos still vote for Trump? Madrid responds to this question by providing reasons why Latinos do not overwhelmingly vote for Democrats. He points out that the common denominator for Latinos is their work ethic—but the stability of the working class is presently under duress. Moreover, Latinos have a strong sense of family connections, but if the Democrats’ sole strategy for recruiting Latinos is immigration policy, then they will continue to see a decline in support, since immigration does not poll as the top concern for Latinos. Finally, Madrid views the progressive left wing of the party as out of touch with the Latino work and family ethic: “Latinos are aspirational voters, largely working poor, working-class, and middle-class, and for the last decade Democrats have become more the party of economic extremes.”

Madrid closes the book looking at the Latino vote in five particular states: Nevada, Florida, North Carolina, Texas, and Arizona. By taking a state-by-state perspective, he shows the sophistication required to court the Latino vote. Finally, the last two chapters address both parties and offer recommendations to each party for improving its relationship with Latinos.

One unfortunate surprise in a book that examines diversity is that Madrid’s understanding of the relationship between faith and politics lacks nuance. For example, Texas politician Mayra Flores commented that pastors should guide elected officials, but Madrid sees this as a slippery slope toward consulting ministers like Iranian mullahs. In addition, he dismisses the significance of religion as a factor in the conversation, declaring that the number of American churchgoers, as well as a more general belief in God, continue to plummet among Latinos. While others have documented this decline in the Latino population, religion still remains a significant enough factor to take into account.

But aside from this, Madrid offers powerful analysis and tools in this book, the result of decades of on-the-ground experience. He explains the urgency of the problem: “The reality is Latinos don’t have a compelling reason to support either party in a meaningful way, and decades of election results exist to prove it.” A close examination of his heroes, Reagan and Bush, who had the “highest level of Latino support,” only makes it all the clearer that the GOP is missing a golden opportunity. In fact, Madrid is certain that if the candidate was someone other than Trump, the GOP might be more appealing to Latino voters.

What about the Democrats? Madrid observes that “they seek turnout based on opposition to Republicans rather than support of what they are selling.” This is not the path for creating deep and lasting loyalty among voters.

Over thirty-six million Latinos are eligible to vote in this fall’s election. Analysts and politicians who ignore Madrid’s book will do so at their own peril.

Michael Jimenez is associate professor of history at Vanguard University. He is the author of Remembering Lived Lives: A Historiography from the Underside of Modernity. He is currently researching the influence of Cesar Chavez’s nonviolent activism and the recent history of Costa Rica.

Interesting article. The Democrats continue to be clueless on how their cultural priorities play out in minority communities, particularly among men in those communities. Though I am no fan of Trump, I cannot look back fondly on the good ol’ days of Reagan-Bush. Yes, they adopted a sunny, optimistic tone in their rhetoric. This appealed to those who believed, or wanted to believe, in the American Dream, both within minority communities and “white” America. Still, the Reagan era saw the end of the American Dream for large sections of the white working class, who nonetheless voted for Reagan. I am curious how this compares with the recent Latino experience. Is it accurate to say that Latinos are experiencing significant enough upward mobility to confirm their commitment to the work ethic and the notion that hard work really does pay off? If so, is this a sign of assimilation into the culture of American individualism? I am thinking of the contrast between what Madrid seems to say about Latinos and the work ethic and an earlier Latino “work” tradition, the labor activism of Cesar Chavez (about whom your bio indicates you are writing). Chavez and his farm workers worked hard, but spoke a rhetoric of community and solidarity rooted in Catholic Social Thought. Has this faded from Latino political culture? Is it a case that the Latino economic base has shifted from agricultural labor to small business, which tends to foster economic individualism?