When hatred turns to pity

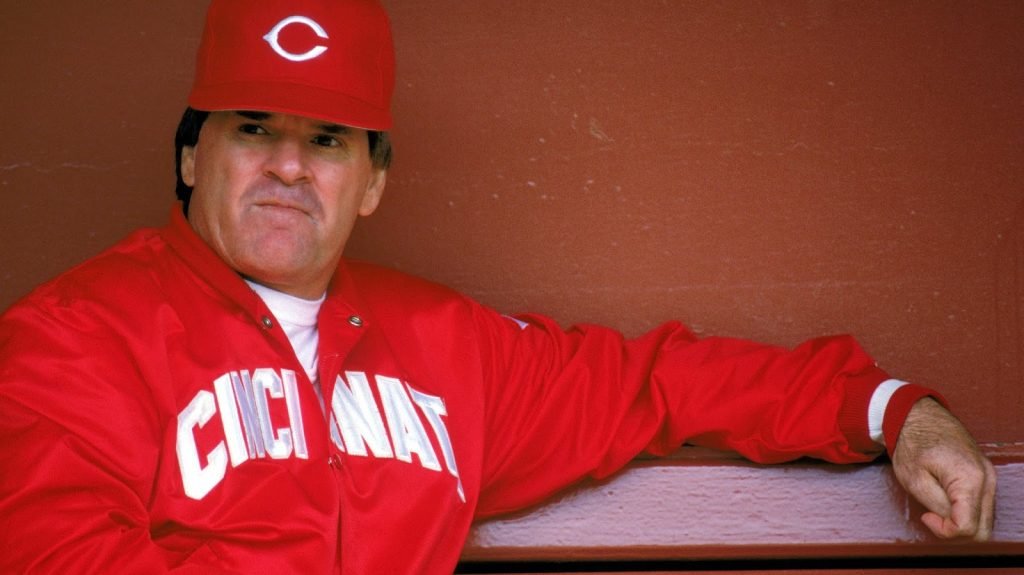

I was never a fan of Pete Rose. When I was a kid I hated the guy.

It all goes back to October 7, 1973, one of my earliest baseball memories. It was Game 3 of the National League Championship series between Rose’s Cincinnati Reds and the New York Mets. The previous day, Mets hurler Jon Matlack had pitched a two-hitter to tie the series at 1-1. After the game Mets shortstop Buddy Harrelson, a lifetime .238 hitter, told the press that Matlack “made the Big Red Machine look like me hitting today.” Before Game 3, while warming-up on the field, Reds second baseman Joe Morgan told Harrelson that Rose was not happy with the Mets shortstop’s postgame comments.

The Mets scored six runs in the first two innings of Game 3, thanks to two homers by Rusty Staub, one of my boyhood heroes (second only to Tom Seaver). By the fifth inning they were leading 9-2.

Then all hell broke loose at Shea Stadium.

In the top of the fifth, Rose, with one out, singled to center field. Morgan followed with a routine grounder to Mets first baseman John “The Hammer” Milner. The Hammer threw to Harrelson at second base to force out Rose, and then Harrelson slung the ball back to Milner for 3-6-3 double play to end the inning.

Rose had slid hard into the bag. This was not unusual for the man they called “Charlie Hustle.” Rose played the game with a kind of physical passion—a fire in his belly— never before seen in Major League Baseball. He would later say, “You know how many second basemen or shortstops I knocked on their ass in my career? Bud Harrelson was just another one.” But sometimes he would tell another version of the story, claiming that he had Harrelson’s remarks to reporters following Game 2 in mind as he tried to break up the double play. The fact that the Reds were trailing by seven runs probably also had something to do with his frustration.

Harrelson and Rose had words. There was pushing and shoving. When Rose grabbed Harrelson and threw him to the ground, I vividly remember watching Mets third baseman Wayne Garrett come charging from the left to tackle Rose. A bench-clearing brawl ensued. Harrelson left the field bleeding over his left eye. The crowd at Shea started throwing debris. Rose, enraged, started picking up bottles and throwing them back at the fans.

The radio call by Mets broadcasters Bob Murphy and Ralph Kiner is worth your time. Murphy was a master at painting word pictures for radio listeners: “AND A FIGHT BREAKS OUT! A FIGHT BREAKS OUT! PETE ROSE AND BUDDY HARRELSON! BOTH CLUBS SPILL OUT OF THE DUGOUT AND A WILD FIGHT IS GOING ON . . . HERE COME THE PLAYERS FROM THE DUGOUT ON A DEAD RUN! . . . AND THE FISTS ARE REALLY FLYING . . . ROSE OUTWEIGHS HARRELSON BY ABOUT THIRTY-FIVE POUNDS.”

After things settled down, Murphy said “someone ought to get thrown out of this ballgame.” (No one did—this was 1970s baseball. You practically had to kill someone on the field to get ejected.) Murphy’s partner Ralph Kiner was quick to note that Major League Baseball commissioner Bowie Kuhn was at the game “seated in the front row of the home plate side of the Met dugout.” Kiner, ever the baseball historian, reminded the listening audience that in 1934 commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis, seated in the stands at Detroit’s Tiger Stadium during Game 7 of the World Series, pulled St Louis Cardinals outfield Joe Medwick out of the game because of a hard slide into third base.

The banter between these broadcasting legends only added to the drama. I was watching the game on NBC. Curt Gowdy and Tony Kubek were great baseball announcers, but they were not Murphy and Kiner. I wish I had known enough then to turn down the television volume and turn up WHN—1050 on my AM dial.

In the bottom of the fifth inning, with a 3-1 count on Mets second baseman Felix Milan, someone in the left-field upper deck threw an empty whiskey bottle at Rose, missing by inches. Rose had had enough. He started walking off the field. Reds manager Sparky Anderson then pulled his entire team into the dugout, telling the umpires the atmosphere at Shea was unsafe for his players. National League president Chub Feeney and Kuhn were seen talking in the stands. A Mets fan lit a Reds pennant on fire with a cigarette lighter and waved it in the air as the flames consumed it. A message to Mets fans flashed on the center field scoreboard: “Interfering with a game can lead to a forfeit. If we must lose, let us be beaten by our rivals rather than by our fans.” And then Mets players Tom Seaver, Willie Mays, Staub (carrying his bat), and Cleon Jones came out of the dugout and walked out to left field to plead with fans to stop throwing things. Other Mets players helped the grounds crew clean up the mess.

By the end of the series, which the Mets won in five games, Buddy Harrelson had secured his legacy as a Mets cult hero. As for Rose? It would be a long time before he stopped hearing the boos whenever he came to Shea.

In my elementary-school world, Rose became Public Enemy #1. Whenever I found a Rose baseball card in a newly opened Topps wax pack I either destroyed it, drew devil’s horns on his image, or reserved it for the spokes of my bike. The future memorabilia market was the last thing on my mind.

Pete Rose died this week at the age of eighty-three. His death has given new life to the ongoing debate over whether or not he belongs in the Baseball Hall of Fame. Rose is one of the greatest baseball players to ever put on a uniform. His performance on the field speaks for itself.

But he also diminished the integrity of the sport by gambling on games while he played for and managed the Reds in the 1980s. Major League Baseball declared him “permanently ineligible” for induction into the Hall of Fame. This week we learned that his “permanent” ban from baseball will outlast his life.

Over the last decade I stopped hating Pete Rose. Now I just feel sorry for him. Anyone who followed Rose during the last few decades witnessed a man who believed that validation from Major League Baseball was his only path of salvation, the only real marker of a life well-lived, the only way to secure a legacy in this world. He pursued reinstatement as hard as his feet-first slide into Harrelson. Baseball was all Pete Rose knew. Too bad he never learned that the gods of baseball do not offer redemption to those who commit the most sacrilegious of sins.

Should Pete Rose be in the Hall of Fame? I do not have strong convictions either way. But I do know that his career is now in the hands of historians. Perhaps the historical debate over monuments that raged during the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020 might help us make sense of what to do about Rose’s mixed legacy. I am leaning toward inducting him posthumously, with no ceremony or celebration, and let Cooperstown tell the complex story of his life on and off the diamond.

John Fea is Executive Editor of Current

Image credit: Otto Greule Jr/Getty

Great story, John. Really takes me back. I too was a Mets and Tom Seaver fan as a kid–until 1986 when my Red Sox loyalties took precedence.

Not much to like about Rose as a person, but the punishment for gambling seems increasingly hypocritical as we see ex-athletes, even “nice” ones like Drew Brees, get paid to promote on-line sports book gambling. And its not just gambling, but obsessive-compulsive gambling, not just on who wins by how much, but on everything that could possibly happen within a game, in real time. Just another one of the many hypocracies within what passes for public morality. I think too of your fond memories of the violence in sports in the 70s. NHL highlights looked like street brawls on ice. Now all of that is forbidden in the name of making sports events more “family friendly.” Yet somehow drag queens like the Sisters of Perpetual Indulgence pass the test of “family friendly.” Sex without limits, but please, no violence! We don’t want to corrupt our youth!

Great points, Chris. I am sorry about 1986. 😉

Ah, this is fantastic. I love good narration about baseball. I grew up in Ohio, closer to Cleveland than Cincy, but Rose’s presence hung over the entire state. Rose was never a guy to say I’m sorry, at least never one to say it where anybody believed him. I think it’ll be a mystery till the end of the world whether or not he regretted any of the regrettable things he did on and off the field. Smashing into Harrelson, jacking up Fosse’s shoulder, playing for the Expos, gambling on the game, etc. Baseball players, at least to me when I was a kid, were knights. Or were supposed to be. Warriors on the field, totally chivalrous everyplace else. Rose was the first ball player I can think of who was a man and not a knight. Whether cognizant of it or not, he dared the fans of the game to see the players of it as humans. Dirty, messed up, hyper-complicated beings for whom baseball was no purifier. We the fans realize, now especially, that what the game means to us is largely an entirely different thing than what it means to the players. It’s a critical distinction. Rose’s gambling preceded the Steroid Era by about three seconds and, astoundingly, baseball fans and pundits are more certain Rose’s memory should live outside the Hall than Bonds, Clemens, etc. Whose sins against the game were far worse. I like the notion that Rose should go into the Hall without the pomp. (Steroid villains should stay put.) Rose probably had a gambling addiction and, back then, nobody could see it via the disease model. Baseball (and the whole world) sees all of that very differently now. Rose, being Rose though, was not one to admit any sort of perceived weakness. Wherever he rests now, I doubt he’s even acknowledged that he’s dead.