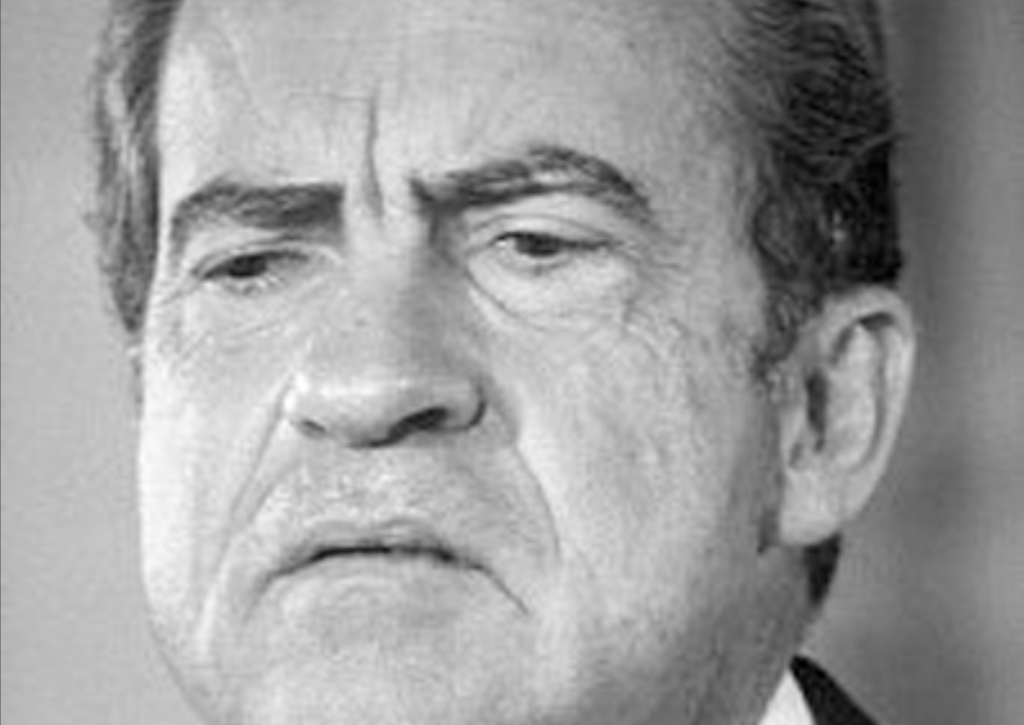

Nixon sought redemption—but on his own terms

One Lost Soul: Richard Nixon’s Search for Salvation by Daniel Silliman. Eerdmans Publishing, 2024. 336 pp., $36.99

I wish that I could have given my grandfather a copy of Daniel Silliman’s One Lost Soul.

For Americans of my generation, it is nearly impossible to imagine what Nixon symbolized for people like my grandfather, who was born in 1930 into a Protestant Republican family in Pomona, California, which would become the heart of Nixon country. For my grandfather—who grew up going to church every week, served briefly in the Army during the Truman administration, and then became a Church of Christ minister during the height of the early Cold War—God and patriotic conservatism were natural allies.

The same was true for Nixon, it seems. After serving in World War II, he launched his political career in southern California as an anticommunist, conservative Republican. His meteoric rise in Congress was primarily due to his painstaking work on the House Committee on Un-American Activities in questioning the respected diplomat (and Communist spy) Alger Hiss and demonstrating that he was lying.

Nixon became vice president of the United States only a few days after his fortieth birthday, and he ran as his party’s nominee for president (and nearly won) before he turned fifty. In the midst of all of this, he cultivated a friendship with Billy Graham, earned millions of anti-Catholic Protestant votes in his race against John F. Kennedy in 1960, and repositioned himself as the candidate of upstanding Christian “law and order” morality in his successful presidential campaigns of 1968 and 1972.

Through it all, my grandfather—like millions of other middle-class, white, Christian Republicans at the time—was a Nixon supporter. He put a Nixon bumper sticker on his car in 1960 and voted for him again in 1968 and 1972. From the time my grandfather was in his early twenties until he reached his mid-forties, Nixon was on every presidential ticket except one. For many white middle-class Americans of the time, he represented the epitome of Protestant Christianity’s anticommunist conservatism.

Watergate, therefore, came as a shock to people like my grandfather. Had they been duped? Was Nixon merely a fraud? Or had there in fact been something noble in Nixon—some redemptive quality that might explain why they had originally believed in him? My grandfather seemed to hope for the latter. Nixon was a “strange man,” he once told me, but at some level he still admired him and wanted to learn more about him.

Twenty years ago my grandfather asked me for a biography of Nixon that was not a hatchet job. He enjoyed the one I recommended—Stephen E. Ambrose’s three-volume saga—but I think Daniel Silliman’s new biography would have provided a better answer to the main question that I suspect interested my grandfather: What was Nixon really thinking, deep in his soul?

As the title of Silliman’s book suggests, this is a study that focuses on Nixon’s soul in a way that perhaps no previous book has. Nixon grew up going to church every week, Silliman tells us, and even when he abandoned the habit as an adult he never stopped seeking redemption. But for Nixon, the redemption had to come on his own terms. As a result, he never really found it.

Silliman acknowledges that Nixon would have disagreed with this interpretation of his story. During his later years, Nixon encountered several psychological studies of himself, and he disputed all of them. The same would no doubt be true of Silliman’s portrayal of Nixon’s psychology—especially since Nixon would have rejected the theological assumptions that guide it. Whether we find Silliman’s interpretation plausible will therefore depend in part on whether we accept those assumptions.

Silliman’s book is based on the assumption that Nixon, like everyone else, was shaped by a deep longing for approval. He needed to know in the depths of his soul that he had done enough to merit commendation from others and that his actions mattered. In Christian theological terms, some might call this a longing for justification. Silliman calls it a longing for redemption—except that for Nixon, this redemption could not come from God’s grace, but only through his own works.

Nixon was the son of a devout evangelical Quaker mother who was deeply pious but who never expressed affection for him. Such possible expression of praise might not have accorded very well with the Quaker emphasis on modesty and humility. Nixon’s father, on the other hand, had not grown up in the Evangelical Friends and had never fully appropriated their theology or practice. He was far less pious, quiet, or humble. He was perpetually angry, especially at his sons. But like Nixon’s mother, his father also found it impossible to show affection for his children. Nixon thus grew up with plenty of teaching about God, but no demonstration of affection. According to Silliman, he never stopped longing for it, even though he never admitted this.

What Nixon did acquire from his father was a religious devotion to work as a means of redemption. Nixon’s father treated God’s curse on Adam in Genesis 3:17 (“By the sweat of thy brow shalt thou eat bread”) as his life motto. He believed that his sons could never work hard enough. When Nixon reached adulthood he threw himself into work and public service. His family had no money for college, but Nixon worked his way through college and law school, maintaining a grueling pace that most students would not have been able to sustain. Despite the Quakers’ longstanding opposition to military service (which would have qualified Nixon for conscientious objector status), he volunteered for the military in World War II and launched a political career immediately afterwards.

According to most biographers, Nixon lost his faith in college, when he accepted the view of one of his professors that the miracles of the Bible never happened. He quit going to church not long afterwards, and he embraced an anticommunist militarism that seemed distinctly at odds with the theology of the Evangelical Friends. He abandoned his earlier Quaker-influenced abstention from alcohol, tobacco, and profanity, becoming an abuser of alcohol and a foul-mouthed swearer whose profanity was memorialized in the recurring phrase of the White House Watergate transcripts: “expletive deleted.” Publicly, Nixon projected an image of Christian morality, attending Billy Graham crusades and holding White House services. Privately, he seemed to be a vindictive, angry deist, rejecting all vestiges of the Christian faith except for a vague belief in a higher power who wasn’t likely to be of much help.

But this was only partly true, Silliman argues. Nixon did become a vindictive, angry, profane man; of that there is no doubt. But his moment of supposed deconversion in college was not much of a change at all. Before that alleged loss of faith, Nixon may have outwardly subscribed to a belief in Jesus’s deity and the claim that Christ was his savior, but it didn’t make any real difference in his life aside from a code of early twentieth-century evangelical Quaker ethics that he found easy to discard. His real religion was work, and his greatest longing was for a redemption that he never found in Christ. After repudiating the tenets of evangelical faith, his real religion continued to be hard work, and he continued his quest for redemption.

But Nixon could never work hard enough to get that redemption. Even when he won elections, he couldn’t win the approval of President Eisenhower or the Republican establishment. And when he lost elections—as he did in 1960 and 1962—he was devastated, though more determined than ever to work harder to earn political redemption. He was uncomfortable around people; at the same time, he desperately needed their approval. That is why as president he routinely called his White House aides late at night to solicit their praise for his speeches—and why he was so angry at anyone who lampooned him.

In the end, Nixon was undone by his own attempts to justify himself. Because of his paranoia about enemies who were out to take him down, he installed a secret taping system in the White House so that he could prove his innocence if he was ever wrongly accused. Ironically, of course, the tapes had the opposite effect: They provided clear evidence of Nixon’s wrongdoing.

Nixon never gave up his quest for self-justification. He almost never attended church during the last two decades of his life. He became more bitter than ever—but also more determined than ever to rehabilitate his image in the public mind.

As it turns out, the millions of people like my grandfather who believed in Nixon, voted for him, and supported him with bumper stickers on their cars may have offered the closest thing to redemption Nixon ever achieved. At some level, Nixon believed that he had let those people down—which he couldn’t bear to admit. He never confessed his guilt, but his resignation devastated him. “I am not a quitter,” he told the American public—only months after he had proclaimed, “I am not a crook.”

Silliman makes a devastating case that Nixon was “one lost soul,” but his analysis left me with a nagging question that his book never addresses: Why didn’t Billy Graham, the most famous evangelical soulwinner of the twentieth century, share the gospel with Nixon directly? Graham met regularly with Nixon to give him political advice about how to win the evangelical vote, he played a leading role in orchestrating Nixon’s White House church services, and he preached the sermon at the first of those Sunday morning gatherings. Nixon presumably heard the gospel from Graham at least indirectly, since he attended several of the evangelist’s crusades. But did Graham ever directly tell Nixon what it meant to surrender his life to Christ? If so, there’s no record of it.

Maybe Graham was afraid to offend Nixon. Maybe he didn’t want to jeopardize his alliance with the man he hoped would bring America back to law, order, and morality. Maybe he really was fooled into thinking that Nixon was a morally upright Christian who just needed a little encouragement to attend church a bit more often. After all, if Nixon managed to convince millions of voters (including my grandfather) that he was a paragon of Protestant morality, maybe it wouldn’t be too surprising if he convinced Graham as well.

Maybe, in fact, Nixon at least half-convinced himself that he was doing a noble work—if not the Lord’s work, at least the work needed to save America. When he realized that he could not work hard enough to earn the justification he wanted, he spiraled downward into a paranoid abyss and took the nation with him.

It’s a tragic story, and it still baffles. How could Nixon be so foolish, one wonders. But Silliman’s biography shows that Nixon’s descent into the abyss didn’t happen overnight. His final actions as president were merely the result of a decades-long quest to redeem himself. That quest took him increasingly farther away from both God and others as he insisted on living his life without the assistance of divine grace.

When my grandfather put a Nixon bumper sticker on his car in 1960, he thought he was supporting a Protestant presidential candidate. As it turned out, Nixon could never accept one of the central ideas of the Protestant Reformation: the insistence on salvation by grace alone. Perhaps it’s hard for any of us to accept it. But as Nixon’s life shows, the alternative to God’s grace can be a quest for self-justification that is unfathomably tragic and destructive.

Daniel K. Williams is a historian working at Ashland University and the author of The Politics of the Cross: A Christian Alternative to Partisanship. He is a Contributing Editor at Current

Excellent analysis

This is an excellent review that explains the disillusionment that many Republican voters like my parents felt. I supported Nixon as a school student in 1960. Very sad,