Reflections on long-tangled webs

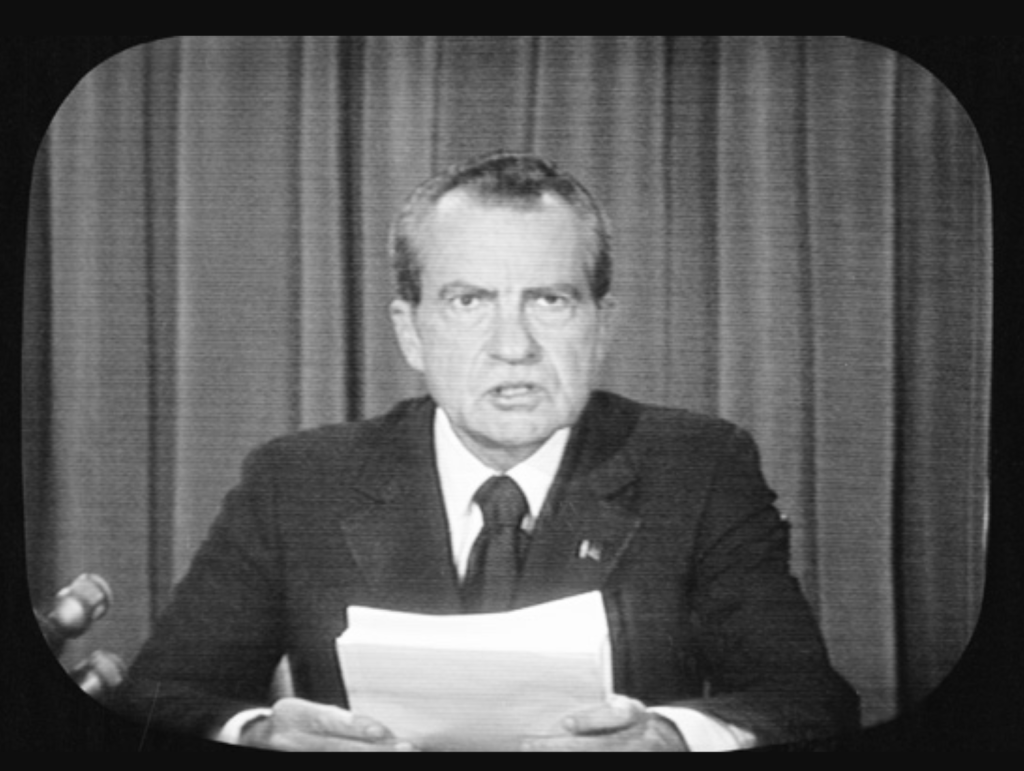

Fifty years ago this week President Nixon resigned the presidency in a cloud of scandal. What does this anniversary mean today? Over the next three days, nine thinkers—historians, political theorists, and journalists—will offer their reflections in response to this question.

***

The exorcism of America

On the evening of August 4, 1974, my teenaged self was in the first row of a soon-to-begin Grateful Dead concert at the Philadelphia Civic Center. At some point I turned around to survey the crowd and saw a huge “IMPEACH NIXON” banner stretched across the balcony, facing the band. It seemed unremarkable to my mind. Of course. Nixon had to go. Why anyone was saying it at that venue was a bit of a mystery, but it made sense to shout the sentiment up into the spheres anyway.

Because Watergate itself wasn’t the half of it. We wanted a new world—though exactly what it would be and who, if anyone, would run it, was unclear. All we knew was the older generation, symbolized by Nixon, was in the way. First things first. There would be time to answer those other questions after we threw the bum out.

Nixon, like other presidents, has benefitted from the inevitable revisions the decades provide. Now we can appreciate certain things about him. Among them: He actually ended the Vietnam War, without victory but without an obvious defeat, either. No easy task. But during his presidency he was vilified as a madman and warmonger. It felt like he was the unqualified embodiment of all the darkest aspects of our national character.

His resignation felt like a purgation, the vomiting out of a poison that would restore the body politic to health. A more ambivalent image was offered by the most iconic film of the moment, The Exorcist—which ran in theaters concurrently with the Watergate hearings—where an innocent young girl possessed by a demon is exorcized by a pair of priests, both of whom die in the process.

The 1960s has been called “the age of great dreams.” Civil rights, the Great Society, the counterculture, the Apollo program, even the Vietnam War itself all partook of a kind of millennialism. Get this one thing done, and something good and true and beautiful—and very large—will happen. The world itself can be born again. The Watergate hearings and Nixon’s forced resignation weren’t just the last gasp of the sixties—they were a religious event, too. The nation had repented. It was free at last. We knew what we were free of. But what were we free for?

Any millennial hopes pinned on the moment were, of course, sheer foolishness. Exorcizing evil, as it turns out, is banal too. Presidents learned not to tape their Oval Office conversations, or to leave any paper trail at all. As for the country, perhaps Hud Bannon said it best, many years before: “This country is run on epidemics, where you been?”

Virtue remained as elusive as ever, inside the Beltway and out. As for great dreams, that age was over. For good and for ill.

John H. Haas is a retired professor of history and Contributing Editor at Current.

***

“I’d vote for him again”

I grew up in Alabama in the 1960s and 70s, a time when the state was transitioning from one-party Democratic bastion to reliable Republican stronghold. In 1968, Alabama had voted heavily for third-party native-son George Wallace, with Democrat Hubert Humphrey also finishing ahead of Republican Richard Nixon. In 1972, however, Nixon swamped Democrat George McGovern in my home state.

I was twelve years old at the time of the Watergate break-in. My father was a carpenter who ran a house-framing crew, and my mother was a secretary. Politics did not play much of a role in our family life. It was not something that we discussed at the dinner table. As a teenager—who had no notion that he would one day be a history professor!—I was only casually attentive to current events.

You couldn’t really help having some idea of what was going on in the world, however. We only had four television channels—the three major networks plus PBS. Everybody watched TV, and news formed a significant area of programming for the networks. Radio stations featured news breaks as well, and for my family (as for many others) a daily newspaper arrived on our lawn every day.

So during the Watergate Scandal we all had a fairly good idea of what was happening. We knew about the hearings and the tapes and the court clashes and the press conferences. But, at least among the adults I knew, I don’t recall any deep level of emotional engagement with the story. It was something that involved a different sort of people in the faraway capital, something relentlessly reported on TV that was taken seriously, but not something that affected our daily lives. I don’t recall any panicky feeling of democracy being threatened or the future of the country being at stake.

Americans had been hit so hard so frequently by tragedies and crises over the previous years that they may have been understandably numbed by the time 1974 rolled around. From the Tet Offensive and assassinations of 1968 to the chaotic withdrawal from Vietnam in 1973, disasters occurred with a depressing regularity.

A couple of remarks my parents made back then have stuck with me. One was more representative of that particular moment, I think, and the other perhaps had more long-term relevance. When the Richard Nixon behind his public image began to be revealed by released transcripts and tapes, my mother was shocked to learn of the vulgar language he routinely used. “I wouldn’t have believed that a president would talk that way!” she once remarked unhappily. This reaction seems decidedly quaint from the perspective of 2024!

On the other hand, I recall my father asserting more than once—both during and after the scandal—“I’d vote for him again.” I remember others expressing this opinion as well. It was based in part on unyielding support of the president and in part on a strong measure of cynicism, a belief that Nixon’s actions represented nothing new among presidents. I remember this attitude being encapsulated in the title of a book published a few years after the scandal: It Didn’t Start with Watergate.

My father became more politically liberal with age, and I don’t think he’d have cared for Donald Trump. But when I consider Watergate in terms of the events playing out today, I think of that simple statement of loyalty that defied whatever the media or anyone else had to say: “I’d vote for him again.”

Steve Goodson is the author of Highbrows, Hillbillies, and Hellfire: Public Entertainment in Atlanta, 1880-1930 and the co-editor of The Hank Williams Reader. He is Emeritus Professor of History at the University of West Georgia.

***

The cynicism that Watergate produced

Perhaps what’s most remarkable about the Watergate scandal is that it shocked Americans at the time. Today it’s hard to imagine being surprised by a president’s effort to cover up his own wrongdoing or giving generic permission to campaign aides to do what seemed necessary to win an election. Even wiretapping an opposing party’s headquarters may not seem terribly shocking today. Yet in the early 1970s, the whole thing scandalized Americans so much that members of both parties prepared to impeach Nixon, forcing him to resign.

Unfortunately, with a loss of shock at presidential bad behavior, we’ve forgotten a few of the positive outcomes that came from the country’s reaction against the Watergate scandal. One thing that emerged from Watergate was the Supreme Court decision United States v. Nixon (1974), which declared that a president did not have immunity from congressional subpoenas. The president is not above the law. This year, by contrast, the Supreme Court expanded the concept of presidential immunity by ruling in Trump v. United States that a president has absolute immunity for some official acts performed in office and “presumptive immunity” for others.

Immediately after the Watergate scandal Congress worked to weaken the “imperial presidency” and investigate possible wrongdoing in the executive branch. Senator Frank Church held congressional hearings to investigate the previously undisclosed activities of the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Congress passed the War Powers Act to limit the president’s ability to take the country into war without congressional approval. Congress also passed the first campaign finance reform laws to limit the influence of money in politics.

In recent years, presidential authority has expanded, and campaign finance reform has fallen by the wayside. Congress is perpetually investigating the president and executive agencies, but no resignations come from those investigations. In our current political climate, it’s hard to imagine a president resigning under bipartisan pressure again.

But there are at least two legacies of Watergate that have endured. The first is investigative journalism, which really began in earnest because of the work of Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein in uncovering the details of the Watergate scandal and tracing responsibility for it to the White House. The second is American cynicism about government.

When Nixon took office, more than sixty percent of Americans said they trusted government to do what was right most of the time or “just about always.” When he left office, only thirty-six percent of Americans held this level of trust in government. With the exception of a brief moment immediately after the 9/11 terrorist attacks, Americans’ trust in government has remained low ever since. Today only twenty-two percent of Americans say they trust government to do the right thing.

Because of his hypocrisy in positioning himself as a moral candidate of law and order and then trying to hold himself above the law, Nixon helped make us a nation of cynics. We’ve lost our sense of shock that a president would do this. But sadly, the cynicism still remains.

Daniel K. Williams is a historian working at Ashland University and the author of The Politics of the Cross: A Christian Alternative to Partisanship.