Our outrage has proven ineffective. What might that mean?

There is a scene in the show Succession in which the Machiavellian patriarch says to his power-hungry but inept adult children, “I love you, but you are not serious people.” They want to take over his company. But to him, the idea is absurd.

The same could be said of us as a country with regard to many things, but perhaps especially to our approach to the protection of children.

In the last couple of years concerned adults have taken their worries about inappropriate books and turned to action. School districts have had to deal with challenges to the curriculum, sometimes even removing books from classrooms. Libraries have also become the focus of anger and activism. Some Republicans are working to remove library funding in many states, with a predictable array of mixed motives. But we should ask ourselves what we would do if we actually wanted to accomplish something.

Consider the facts. How many small children are going into libraries unaccompanied and leaving with books their parents deem inappropriate? Are more children being corrupted by books than by television and movies? Children eight to twelve spend four-to-six hours a day watching screens—considerably less than reading books. Any effort to protect children from content would not begin with books and would not focus on libraries. And a sincere effort to go after school curriculum that would not require state legislation insisting that adults challenging books without a child in the relevant school be limited to a certain number of challenges per month.

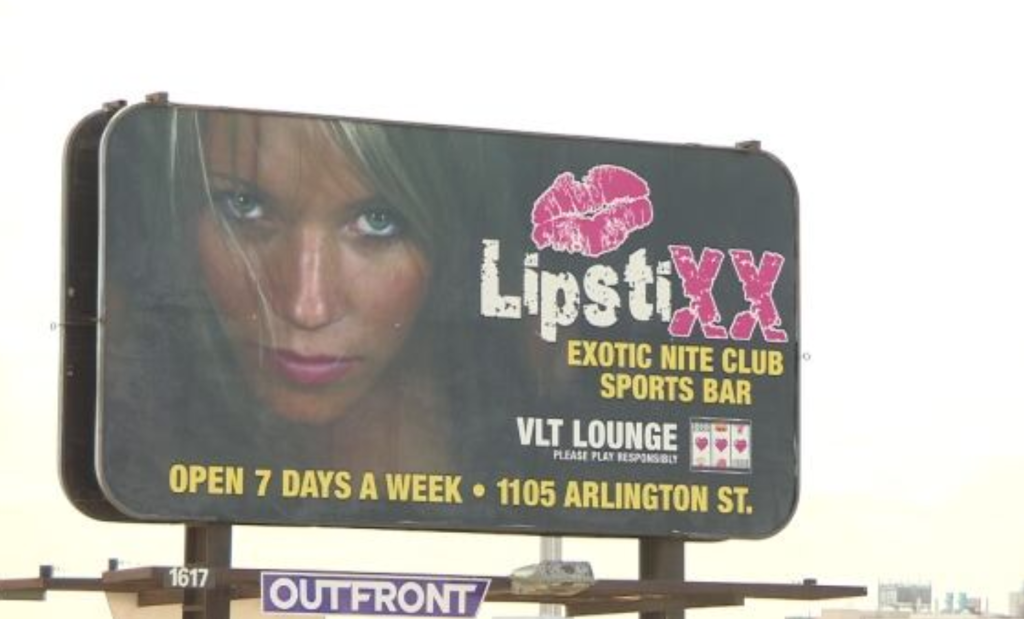

If we want to protect children from inappropriate content, allow me to suggest a new focus. Why can’t we go after billboards first? I can drive to and from work a variety of ways and not go by a single library. But I cannot drive to and from work and easily avoid a provocative billboard for a strip club. They litter the highways in Palm Beach County, Florida. Parents can control what books their children check out of a library. How can they stop their children from seeing scantily clad women with suggestive phrasing out the car window? They can’t. And what about every fall when the billboards are advertising “Halloween Horror Nights” with images that are sure to give elementary-age children nightmares? Where are the concerned citizens then?

The “concerned” parent and citizen movement (which includes the “parental rights” people) has a fatal flaw: They will not go after monied interests. They will weed out libraries, but they leave softcore pornography in plain sight. No doubt it is a lot easier to take on librarians than strip club owners. One side has the money and many more influential patrons. But a library in your neighborhood is less likely to foster drugs and prostitution and excessive drinking and personal debt. How many strip clubs are within a five-mile radius of my house, which is in a neighborhood with a pricey homeowner’s association? Six.

Too many of our attempts to “clean up” the world seem designed to make us feel better without solving problems or causing trouble for powerful people. The same goes for many of our efforts to end sex trafficking. We put up signage everywhere, we increase awareness, we want to rescue people—and all of that is good. We talk about it all the time. But while we do things to address the supply side of the issue, we do next to nothing on the demand side. While people who pay for sex are the reason trafficking exists, we rarely prosecute them. Consider the case of Robert Kraft—again, in my county. He was busted in prostitution sting and walked away without charges. Kraft was not involved in sex trafficking, but Jeffrey Epstein was and he lived here, too. And authorities knew more earlier than you wish was true. Again, we show no interest in going after monied interests, but so often people with money are deeply involved in the demand side of trafficking (sexual and otherwise).

The problem with our ineffective outrage is that it makes us feel morally righteous and it allows us to ignore too many realities. Sure, you can get around things with a virtual private network. But why do the majority of states not require age verification for Pornhub if we’re so worried about what children might see? Are children really coming across inappropriate books as often as they accidentally (or on purpose) come across pornography? Why is it that a majority-minority middle school near my house does not have a school zone for traffic regulation? I hear about “awareness” for child protection all the time at work and church. There are children down the street who we do not even protect from speeding cars.

We are not serious people. We say we want to protect children from inappropriate content and end trafficking, but we think we can do that without going after anyone with money or power. Effective efforts will inconvenience us and will certainly upset people who have an interest in the corruption and endangerment of young people. Ours is a sorry story—and the story we’re telling ourselves is especially sorry: a tale “told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.”

Elizabeth Stice is a professor of history at Palm Beach Atlantic University, where she also serves as the assistant director of the Honors Program. She is the author of Empire Between the Lines: Imperial Culture in British and French Trench Newspapers of the Great War (2023). In her spare time, she enjoys ultimate frisbee and putting together a review, Orange Blossom Ordinary.

I liked these thoughts but it occurred to me that libraries are generally, historically considered a safe or healthy influence, a depository of ideas for learning and such. Trying to control the books in libraries might seem more reasonable to parents who want to let their children explore the world in a way that seems “safe” to their parental imagination. Strip clubs and softcore porn, on the other hand, are private interests that are inherently adult, aimed at not children. The complaint of the article is like an attack on people who want to keep impurities out of the water, using the argument that they might be better of haranguing the alcohol industry because beer is worse than water.

I’ve never, ever complained about libraries or campaigned against books. But not that long ago my nine year old came home from the local library with a book for small children titled “Swinging.” The story is about different letters of the alphabet (v, o, e, l) who can’t get along until they swing together. It was authored by a pansexual/gay activist who travels to different schools and reads to kindergartners. The entire book was a bad metaphor for how sexually swinging can make L-O-V-E happen between strangers. But it was designed, deliberately, to slip under the parental radar and sit in childlike brains until it clicked later that the author was talking about promiscuous and kinky sexual practices.

Books are different than images. They supply thought material that can transform over time in calculated ways. Being aware of what your kids watch is also important. But there is no effort to target kindergartners with adult messages in a strip club billboard.