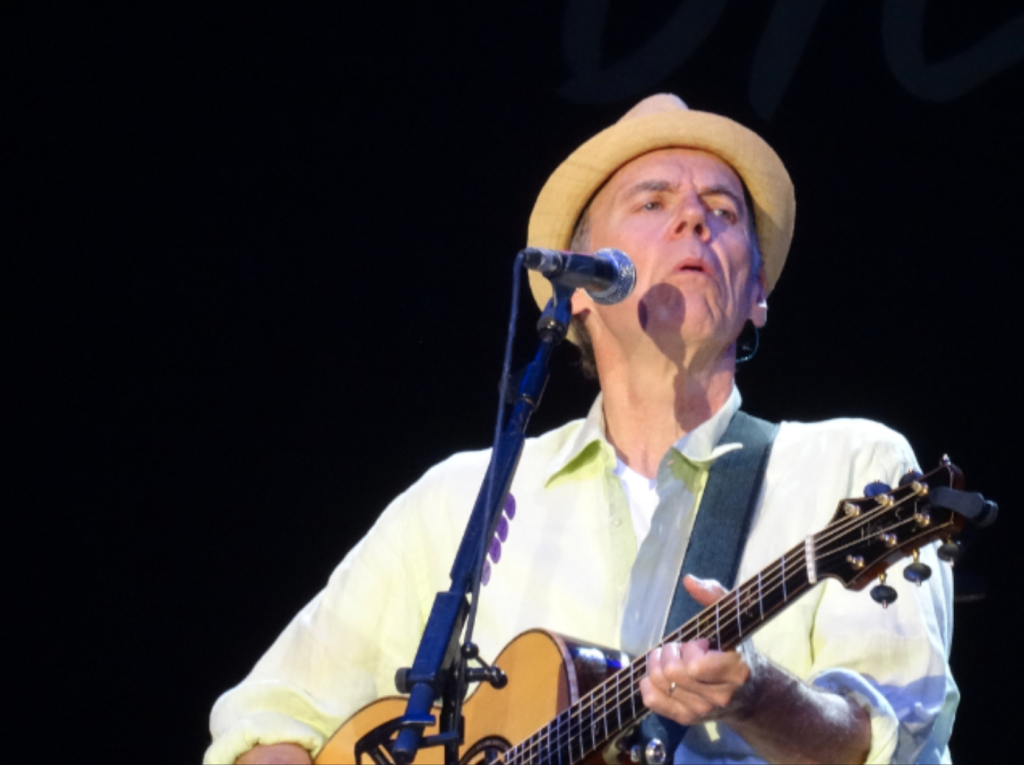

At 71, John Hiatt’s still showing us how it’s done

1. May 2004

Mr. Smalls used to be St. Ann’s. The church opened in 1924 along the Allegheny River in the old Pittsburgh neighborhood of Millvale, about four miles from Pittsburgh’s famous “point,” the confluence that forms the Ohio. St. Ann’s closed in 1998 and reemerged in 2002 as a music venue. My wife and I arrive for a concert imagining that we’d bought seats. Instead, we find about fifty folding metal chairs in front of the stage and a horde of people dancing and drinking—maybe 500—where priests and parishioners once met.

My back is throbbing from a week of getting the garden in. I’ve got heat pads belted around my waist. We work our way toward the front edge of the hall, past the bar, and discover a pew pushed against the wall. Eventually it empties enough for us, gratefully, to sit down. We can see most of the stage. We also see a lot of bodies between us and it. We’re in our mid-thirties and the crowd, in a state of liberated, expectant motion, has five or ten years on us.

John Hiatt steps out, and roots rock flows. He and his band are focused, sharp, and true. They deliver a rowdy confection of rock, country, blues, gospel, and folk that tastes like America past, America present. Hiatt, fifty-one, plays the guitar and some keyboard. At the keys he belts out “When We Ran,” remembering a mad dash away from intimacy, from possibility. He mentions that as a boy in Indianapolis he listened to a Chicago station that played gospel, and years later it came out in the impassioned prayer he sings, “Is Anybody There?”—a sane run in the other direction, toward hope, God, marriage. He sings and sings, words whimsical, sardonic, sincere, profound, as the realities he evokes require.

The crowd rocks along through his breakthrough albums of the 80s and 90s—Bring the Family, Slow Turning, Stolen Moments, and more—clapping, dancing, shouting. We’re still on the pew when they really let loose. A woman in front of us sways and gyrates as if entering glory itself. After a minute she spins around, looks us dead in the eye, sees that all we’re seeing is her, and boogies right on, glory in view.

We’ve been listening to Hiatt for ten years and know most of the songs—songs about regret and rescue, about the terror of infidelity and the blessedness of union. But one we don’t know is one everyone else does, and they join him in the chorus with such ardor that it echoes in my mind for days. “Looking for his Buffalo River home,” they sing, a soul-struck choir. As Hiatt blazes through his encore we rush out to relieve a faithful babysitter who’s been hanging steady with our three boys all night.

2. March 2010

It’s almost spring and Hiatt is touring his new album, The Open Road. Ian, our oldest, has just turned fifteen. He is eager to see the man he’s heard from the back of the car over many a road.

The concert’s being held along the other river, the Monongahela, seven miles from the confluence at the Carnegie of Homestead Music Hall, located within the sixth of the 2,500 libraries Andrew Carnegie commissioned. This one opened in 1898, six years after Carnegie’s militia killed and maimed his striking steel workers in the infamous Battle of Homestead. The library presides serenely on a hill above the town in a kind of victor’s stance. The steel workers aren’t the only ghosts hanging around. The Negro leagues’ venerable Homestead Grays once lived and moved and had there being here, their great ones’ names yet uttered with reverence—Josh Gibson, Buck Leonard, Cool Papa Bell.

Ian and I arrive in time to eat dinner on the site of the Homestead Steel Works—now occupied by (per Wikipedia) a “superregional open-air shopping mall” called The Waterfront, situated along the river as if deposited by crane, one massive amalgamated whole. Twelve soaring smokestacks edge the shopping area, preserving the heritage. As it were.

The hall seats a little more than a 1,000 and we’re on the balcony looking down, a grand chandelier above, aged wooden floors below. It’s an intact Beaux Arts surround. Hiatt is at his mercurial best, growling, whispering, laughing, crooning, his band synced to him like a circus master. They roll out “Thank God the Tiki Bar Is Open” as if it’s Halloween in the French Quarter, a wild and festive rendition of a darkly ironic song. “I know drink ain’t no solution,” Hiatt sings. “I ain’t had one in seventeen years.” But amid our twenty-first century surround—fluid high-tech artifice—even the tiki bar has acquired institutional solidity—a place of anchorage as much as escape. How can we escape our constant state of escapism? This is one of Hiatt’s fundamental questions.

I was out on a leave of absence

From any resemblance to reality

I felt like a rocket launched to the great blue yonder

From the boys down at Kennedy

And so: “If that tiki bar was closed tonight / Well, I might just disappear.”

“I know times bent on destruction,” Hiatt had mused in “Fly Back Home.” “The past is over every day.” No trim row of smokestacks can halt our dedicated obliterating of the past, of ourselves. We can at least begin admitting that it’s happening.

This library, though, has been essentially untouched over its 112 years. Its antique amalgamated form will no doubt outlast The Waterfront. They made foyers small in 1898, and at the end of the show Hiatt greets us in this one, seated behind a table, signing whatever gets thrust toward him. I buy a pack of purple John Hiatt guitar picks; Ian asks him to autograph his concert ticket. “Do you play guitar?” Hiatt asks him. Ian nods. “Keep playing!” He does.

3. May 2024

Fourteen years pass and Hiatt is playing in Homestead again. I am now the age he was when we saw him in 2010: fifty-seven. I still use the guitar picks. Ian lives in Japan. Our middle son and his wife live six miles away in a neighboring town. Kit, our youngest, has just graduated from college, and he wants to see the man himself. He and a friend from college bonded in recent months over a Hiatt album: Crossing Muddy Waters. His friend is a Brazilian.

Kit sits between his mother and me; we’re perched on chairs designed for smaller Americans—for a smaller America. Hiatt, alone this time, situates himself on a captain’s chair, with two guitars and a rack of harmonicas. The songs are the old ones, the great ones, songs of longing, loss, fidelity, and peace. “Like a Freight Train” laments, in a bluesy wail, middle-aged decline. But “Feels Like Rain” takes us to New Orleans, where “love comes out of nowhere / just like a hurricane.” It’s “our song,” or one of them. And though I can’t see my wife, Kit is anything but in the way. We’ve done what Hiatt long ago told us to do: We brought the family.

The hall is packed, and it’s filled with joy, shouted out (“We missed you, John!”) and offered up in claps and sing-alongs, often enough. But mainly, two decades on, we sit with quiet conscious gratitude. We are there in pairs, mostly. We’ve raised our families; our careers are over or winding down. But real life surges on. And Hiatt’s still there, showing us how it’s done. For all his success—nine Grammy nominations; covers by more than 200 artists, among them Bonnie Raitt, Bob Dylan, Buddy Guy, Linda Ronstadt, Clapton and King—this is what remains.

Hiatt had vowed in his fifties, “I wanna go down singing, Hallelujah Gabriel / I wanna go down singing / ‘Boy, you played the blues so well.’” Anyone who listens to Hiatt knows—to his immense artistic credit—what a close call it’s been, and no doubt still is, the escape from the hell of his own ruins. Anyone who knows themself knows the same. But heaven is there waiting, he tells us, in a thousand ways. All it takes is a faithful embrace—something heaven’s always ready to offer.

Eric Miller is Professor of History and the Humanities at Geneva College, where he directs the honors program. His books include Hope in a Scattering Time: A Life of Christopher Lasch, and Brazilian Evangelicalism in the Twenty-First Century: An Inside and Outside Look (co-edited with Ronald J. Morgan). He is the Editor of Current.

Wonderful vignettes, Eric. Now I know what to start listening to next. You will be pleased to know that I have tickets for tonight to see (and, most of all, hear) Gregory Porter.

Many thanks, Tim. I saw Porter at the Pittsburgh Jazz Festival in 2018 and can still hear the medley he sang that centered on “Musical Genocide”: one of the fiercest, most powerful musical moments I’ve ever experienced, on a blocked-off street in Pittsburgh’s Cultural District on a hot June day. I hope your evening fills you with memories (maybe some that you’ll write about?!).

“… but let my brother’s hamster burn in hell.”

Eric, not only is this lovely (especially the way you’ve marked time-life-love with this man and his music), but it makes me wonder if our next theological virtue/Pieper book session needs to begin with a Hiatt song.

Hey Julie–now that’s an idea. A few dozen come to mind–like this duet with Innocence Mission’s Karen Peris (most unexpected pairing).