Good Friday is the day on which Christians reflect on a truth that has long been controversial: the doctrine of atonement. God in the person of Jesus Christ took our sins on himself in order to pay a price that we could not pay.

Many of the founders – including Thomas Jefferson and most likely John Adams and George Washington – rejected this doctrine. The justice of God made sense to them. The love of God appealed to them. But the idea that justice and love would meet in the act of atonement seemed barbaric – a throwback to the pagan sacrifices of the ancient world.

And if the doctrine of divine atonement struck some of the Founders as barbarism, it seemed equally archaic and unnecessary to Americans in many other eras. Even a lot of professing Christians find the doctrine hard to swallow.

One might think, therefore, that such an allegedly antiquated and barbaric doctrine as atonement would have long ago been discarded – but it hasn’t been. When faced with the reality of horrific evil, we instinctively feel the need for some sort of sacrifice to atone for it – and if it’s not going to be Jesus’s sacrifice, it will have to be someone else’s or perhaps even our own.

When faced with the massive evil of race-based chattel slavery and the horrific sacrifice of human life in the Civil War, some Americans drew a connection between the two and decided that the deaths of Union soldiers were atoning deaths meant to pay the price of sin.

“As he died to make men holy, let us die to make men free,” Julia Ward Howe wrote at the beginning of the war in her “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

That particular line in the hymn followed three stanzas about God’s coming judgment. God was “trampling out the vintage where the grapes of wrath are stored.” He had “loosed the fateful lightning of his terrible swift sword.” He was “sifting out the hearts of men before his judgment seat.” But then, interrupting all of this in the fourth verse of her hymn, was an act that seemed to promise redemption: Christ was “born across the sea.” And yet Howe stopped short of saying that Christ could stay God’s hand of judgment on the American continent in her own time. Instead, people would have to die so that others could be free. The judgment would fall on them.

Surveying the end of the conflict, President Abraham Lincoln seemed to come to a similar conclusion. The Civil War might have been God’s act of judgment on the nation for its sin of slavery, Lincoln reflected. “If God wills that it continue until all the wealth piled by the bondsman’s two hundred and fifty years of unrequited toil shall be sunk and until every drop of blood drawn with the lash shall be paid by another drawn with the sword as was said three thousand years ago so still it must be said ‘the judgments of the Lord are true and righteous altogether,’” he declared in his second inaugural address.

Over the next century and beyond, the idea of atonement reappeared whenever Americans thought of making a supreme act of sacrifice – either of their own lives or of the lives of others. At times, the sentiment could be noble, as it was when Martin Luther King Jr. told a crowd of 200,000 civil rights activists gathered on the Washington mall that they should return to the jail cells and the dangers of their local communities because “unearned suffering is redemptive.”

At times, the sentiment could be horrifically sadistic – as it was when lynch mobs reenacted the crucifixion in order to purge their communities of an alleged evil by executing Black men whom they accused of horrific crimes. Both Blacks and whites in the South saw the obvious connection with atonement. White members of the lynch mobs saw themselves as the purifiers of their communities who were sacrificing criminals in order to atone for the crimes those alleged criminals had supposedly committed. Blacks, on the other hand, identified the lynching victims with Christ, who had also suffered unjustly.

But the tragedy of all of these efforts at atonement – both the noble self-sacrifices and the vindictive, cruel sacrifices of the bodies of others – is that they couldn’t wash away guilt. The hundreds of thousands of deaths in the Civil War could not get rid of the effects of race-based slavery; the effects are still with us to the point that many have called slavery the nation’s “original sin.” And if the Civil War could not really be an act of atonement, lynchings certainly could not; indeed, the more lynchings that occurred, the more the calls for vengeance continued.

Our own acts of atonement seem to repeatedly come short. At best, they fail to take away either the guilt or the effects of sin. At worse, they become spectacular blood-baths that far outstrip the crime and exacerbate a cycle of violence.

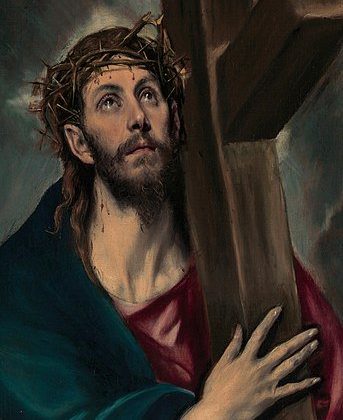

And so we come back to Christ’s atonement – an act that absorbed violence rather than perpetuated it. Jesus came into a violent, sinful world and then, as God in the flesh, allowed the creatures that he had made to put him to death. He absorbed their violence and then triumphed over it. And because he was absorbing the violence as both a sinless human and as God, he was able to accomplish a reconciliation and redemption that even the most noble-minded self-sacrifices of ordinary humans have been unable to achieve.

And once that happened, we don’t have to try to atone for evil ourselves. We believe that the sacrifice of Jesus was sufficient.

The cross reminds us of the magnitude of human evil – a magnitude that is far greater than eighteenth-century deists and others who have denied the need for atonement could ever have imagined. But it also reminds us that we don’t have to seek atonement through our own means, because a perfect atonement has already been given.

The history of our nation suggests that when we seek our own methods of atonement, the results are not only horrific but also unsatisfactory; they don’t remove the evils they were supposed to atone for.

Christ’s atoning sacrifice frees us from our efforts to atone for ourselves. That’s the enduring power of the cross. And on Good Friday, we remind ourselves that our guilt really has been taken away and our sin atoned for.

Yes, we see horrific evils around us – evils that are so great that they can’t be whitewashed or dismissed without consequences. But because of the cross, we don’t have to seek our own revenge or atone for those evils ourselves. God has already done what we could never do. And he has done so not through inflicting violence on us but by choosing to experience violence against himself so that we could be forgiven and free.