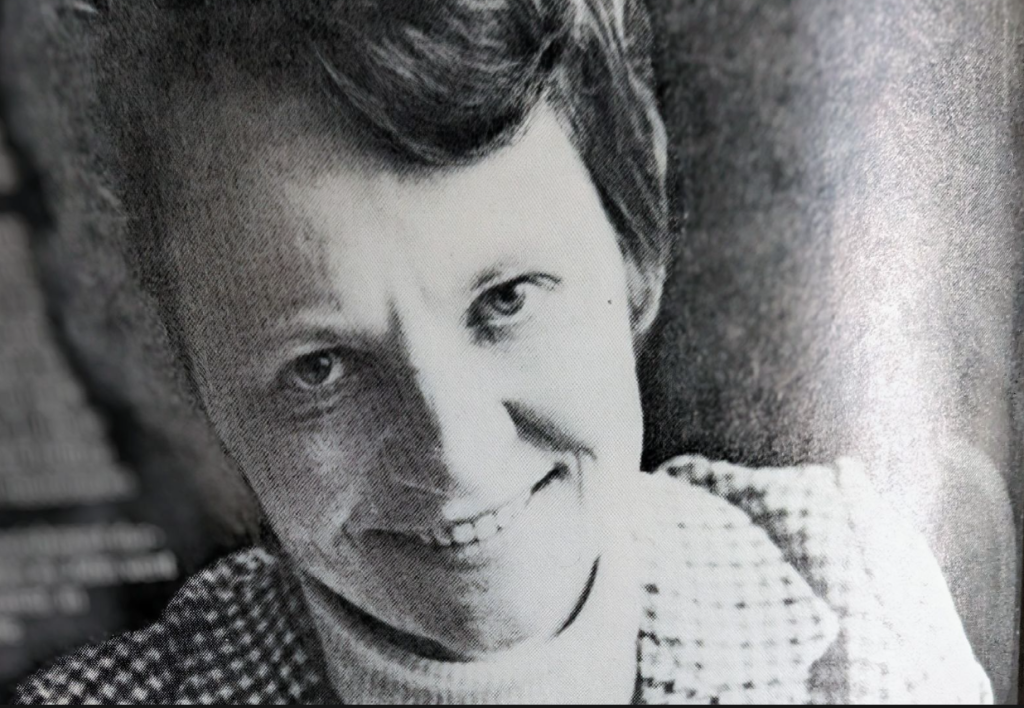

Letha Dawson Scanzoni’s legacy lives on

In 1968 Christianity Today and the Christian Medical Society hosted a symposium called “The Control of Human Reproduction.” It gathered thirty-five ethicists, medical professionals, theologians, and sociology researchers to consider what a Christian response to reproductive rights, including contraception use and abortion, should be. The results of their work, published as “A Protestant Affirmation on the Control of Human Production,” included recommendations that would be considered heresy to many of today’s prolife evangelicals; the document advocated for a far more nuanced understanding of reproductive rights, one that acknowledged the need for laws that are neither “too authoritarian, or too permissive.”

This past week I’ve been reading again about this symposium, in part because the fifty-first anniversary of Roe v. Wade has just passed, as has the National March for Life, with all the attending inflamed rhetoric that generally accompanies these events. But I’ve also been thinking about the 1968 symposium because one of its attendees, Letha Dawson Scanzoni, died in early January at age eighty-eight.

Few people today know that many white evangelicals at one time had a considerably more moderate stance on abortion, though scholars like Randall Balmer have traced this history of the Religious Right and its use of the abortion issue to gain power. And fewer still know of Scanzoni, nor her prophetic work intended to help women gain equity and become—in her words—”all God created them to be.”

Scanzoni attended the symposium as an invited guest: Her then-husband was speaking, and families had been invited to the New Hampshire shoreline alongside the thirty-five men who presented. Years later Scanzoni wrote that she skipped the organized events for wives and children at the symposium, choosing instead to listen to the all-male panel make suppositions about women and their reproductive health. “In one session, I was sitting beside the wife of a well-known minister,” Scanzoni remembered. “She whispered, ‘I just marvel at the way these men’s minds work.’ I agreed, but ached to say, ‘It could be women’s minds working, too!’ I yearned to be up front joining in the discussions and speeches.”

This longing to have women’s voices heard within Christian communities became the defining work of Scanzoni’s life. Her book All We’re Meant to Be: A Christian Approach to Women’s Liberation (1974), written with Nancy Hardesty, articulated what were revolutionary ideas: that women could be free from gender stereotypes, and that they could use every skill God had given them, including the gifts of Christian leadership and preaching. Scanzoni and Hardesty based their perspective on a biblical interpretation that offered readers liberation and, in 2006 Christianity Today named All We’re Meant to Be one of the top fifty books “that have shaped evangelicals.”

Scanzoni’s work provided a blueprint for Christian feminism, opening doors for countless women for generations to come. Along with other second-wave feminists, she helped form the Evangelical Women’s Caucus, an organization advocating for non-sexist language in Christian publishing, educational opportunities for women, nondiscrimination clauses in employment, and egalitarian marriages. A number of significant works emerged from the group’s meeting in 1975, including Virginia Ramey Mollenkott’s Women, Men, and the Bible, another book arguing for women’s freedom from the constraints of gender expectations. (Later, in 1978 Scanzoni and Mollenkott wrote Is The Homosexual My Neighbor?, one of the first books to argue a biblically-based affirmation of LGBTQ people.)

Like most prophets, Scanzoni and her liberating message faced fierce resistance from evangelical leaders and laity alike. Theologian Wayne Grudem claimed her work “rejected the authority of scripture,” and some have argued that Grudem’s Council of Biblical Manhood and Womanhood was formed to combat the emerging feminist movement within evangelicalism of which Scanzoni played a major role. James Dobson, who had written the preface for Scanzoni’s 1973 Sex is a Family Affair, tried to pull his endorsement from later editions of the book, believing an association with such a radical would be problematic. After her public advocacy for Christian feminism and for LGBTQ people, she lost speaking and writing opportunities but remained faithful to her message—perhaps because she ardently believed her message was also that of the God she served.

Grudem and others, at any rate, had judged her wrongly: Rather than rejecting the authority of scripture, Scanzoni turned to the Bible to craft her ideas about gender and sexuality. In a recent remembrance, scholar Kendra Weddle observed that “Letha always saw herself as an evangelical. She knew Scripture and could quote chapter and verse with the most ardent biblical scholars. But more than that, the Bible was a constant source of inspiration and guidance. She also experienced a vibrant relationship with Christ.”

On her FemFaith blog (for which I was also a contributor), Scanzoni wrote that “There was once respect for differing viewpoints among evangelical Christians in a way we seldom see in the present time—and a humility of spirit in the realization that not all the answers are in on some of these tough moral and ethical questions.” Her observation, written in 2011, could not have anticipated the current cultural climate and a more deeply divided country, one where a humble respect for different viewpoints is rare—and rarer still among the evangelicals with whom Scanzoni identified.

With Scanzoni’s death, an important voice about the history of late-twentieth-century evangelicalism and women’s liberation may be lost. Scanzoni was an inveterate saver, though, and her papers are housed at the Burke Library at Union Theological Seminary. Significantly, her life’s work of fighting for gender justice lives on, even in younger Christian feminists who do not know about her influence. After all, her writing and advocacy opened doors for others, allowing people to become who they were uniquely created to be.

Melanie Springer Mock is Professor of English at George Fox University. Her books include Finding Our Way Forward: When the Children We Love Become Adults (2023), Worthy: Finding Yourself in a World Expecting Someone Else (2018), and If Eve Only Knew: Freeing Yourself from Biblical Womanhood to Become Who God Expected You to Be (2015). Her essays have appeared in Christian Feminism Today, Literary Mama, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Brain, Child, and Runner’s World, among other places. Much of her work focuses on her experiences parenting, feminism within Christian context, and social justice.

Letha’s and Nancy Hardesty’s book, ALL WE’RE MEANT TO BE, was one of the most important books I read as a young wife and mother in the 1970s and (along with Mollenkott’s book) completely changed my understanding of the role of women in the church and society. I am grateful for her prophetic legacy.

Thanks for the comment, Harriet. I had never heard of Letha Dawson until Melanie sent us this piece.

Thanks, Melanie, for painting the scene of this 1968 symposium on “The Control of Human Reproduction” hosted by Christianity Today and the Christian Medical Society. Hard to believe that it was all men speaking to and with each other while women were relegated to “organized events” along with children–and just five years before the Roe v. Wade decision. The nerve of those men! Of course Letha would be right there in the room, marveling to see an “all-male panel make suppositions about women and their reproductive health,” yearning to be on the panel herself. She had written books on sexuality for teens and would go on to co-write a college textbook titled Men, Women, and Change: A Sociology of Marriage and Family. The marginal place of women in the scene you evoke brings me to tears.