America’s founding meant something very different for King than it does for today’s Christian Right

What would you think if a political activist gave a speech outlining a vision for the nation’s future that he said was “deeply rooted in the American dream”—and if he then elaborated on that vision by quoting several passages of scripture and concluding with a rousing recitation of the patriotic song, “My Country ’Tis of Thee”? Would you say that that political activist was a Christian nationalist?

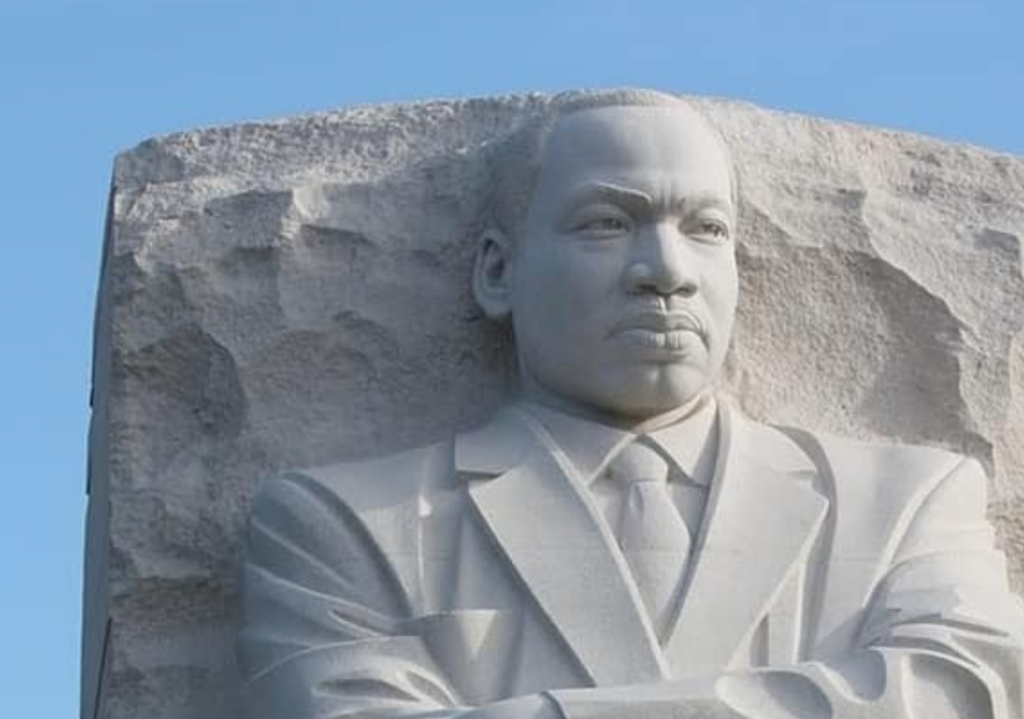

That political activist, of course, was Martin Luther King Jr., and the speech was his famous “I Have a Dream” address.

King has perhaps rarely been called a “Christian nationalist.” Yet his speeches were suffused with biblical quotations, Christian imagery, and an appeal to the nation’s founding documents—the very things that often characterize contemporary Christian nationalism.

Perhaps for that reason I should not have been surprised when I encountered a conservative seminary professor a couple weeks ago who insisted that King was in fact a Christian nationalist. I didn’t entirely agree. But if King wasn’t exactly a Christian nationalist of the modern sort, neither did he share the assumptions of many modern critics of Christian nationalism. So what was King’s stance toward Christian nationalism?

If we define Christian nationalism as the belief that the American nation was founded on Christian principles and that we need to return to those principles today, some of King’s statements do seem at least vaguely Christian nationalist. King frequently conflated the principles of the Constitution and the Declaration of American Independence with the teachings of scripture and Jesus Christ, as though the two sets of documents—the secular and the sacred—said exactly the same thing.

When he called for the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955, for instance, he told the people assembled in Montgomery’s Dexter Avenue Baptist Church, “If we are wrong, the Supreme Court of this nation is wrong. If we are wrong, the Constitution of the United States is wrong. If we are wrong, God Almighty is wrong. If we are wrong, Jesus of Nazareth was merely a utopian dreamer that never came down to earth. If we are wrong, justice is a lie. Love has no meaning. And we are determined here in Montgomery to work and fight until justice runs down like water, and righteousness like a mighty stream.”

For King, there seemed to be no real difference between the message of a pro-civil-rights Supreme Court, the Constitution of the United States, the teachings of Jesus, the message of the Hebrew prophet Amos, and the declarations of “God Almighty”: All of them were on the side of justice, love, and truth.

He was still preaching this message the night before his assassination, when he gave a speech that again quoted his favorite passage from the prophet Amos, appealed to the teachings of Jesus, and cited some of the principles from the Bill of Rights. “All we say to America is, ‘Be true to what you said on paper,’” King declared in his final address.

Some advocates of civil rights did not share King’s faith in America’s founding documents or in the American nation. Instead of preaching an American nationalism or a Christian nationalism, Malcolm X advocated what he called “Black nationalism”—an idea that had inspired Marcus Garvey’s pan-Africanist movement a generation before and that had a long tradition among some African Americans. According to this view of American history, the United States was founded not on divine principles of justice but on racism and oppression, and the founding documents therefore offered no real hope to African Americans. As Malcolm X said, “We are not Americans. We are a people who formerly were Africans who were kidnaped and brought to America. . . . We were brought here against our will; we were not brought here to be made citizens. We were not brought here to enjoy the constitutional gifts that they speak so beautifully about today.”

In the battle today over critical race theory, some of the critics of Malcolm X’s Black nationalism have championed Martin Luther King Jr. as an alternative. King believed in Christianity, they point out. King believed in America’s founding documents and thought that African Americans were included in them. King, in essence, believed some of the same things that modern Christian nationalists believe.

Some of the modern critics of white Christian nationalism respond that King was deeply critical not only of American racism but also of American military power, the American economic system, and the way the nation treated the poor. King was a prophetic leader; he was not a Christian nationalist. He was also a committed pluralist whose faith was thoroughly ecumenical.

Who is right? Was King a Christian nationalist? Or a prophetic critic of American power?

Maybe he was both: both an advocate of the idea that the American founding documents enshrined important Christian tenets of justice and a prophetic critic of the nation’s unwillingness to live up to those ideals.

Like modern Christian nationalists (and unlike Malcolm X and many Black nationalists), King believed there was something good about the American founding and that African Americans could lay claim to its promises. He also believed that whatever was good about the American founding was good because it reflected God’s eternal principles of justice—the same principles that pervade Hebrew scripture and the teachings of Jesus. Like Christian nationalists today, King believed in the American nation and in the teachings of Jesus and scripture, and he thought we would be a better nation if we lived out the Christian principles of justice that are outlined in some of the lines of the Declaration and the Constitution.

But if King was a Christian nationalist, he was a prophetic Christian nationalist who saw the fulfillment of America’s promise not in a return to the past but in a progressive move toward a very different future through a collective national repentance. The principles of the Bible, the Declaration of Independence, and the Constitution contained everything that was needed to bring about a just social order in the United States—everything that is, that could be written on paper. But “instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked insufficient funds,” he declared.

For those who love their country and the divine principles of justice in the way that King did, the task is clear: We must critique the country in love and call it to a better future—not because of a lack of love for America’s founding but because of a love for the nation’s founding values and a realization that America is not living up to them.

That’s not what people often mean today by the term “Christian nationalism.” But that’s the type of prophetic Christian nationalism that King preached. And for those today who love the American nation but are all too aware of some of its flaws, the sermon still resonates.

Daniel K. Williams is a historian working at Ashland University and the author of The Politics of the Cross: A Christian Alternative to Partisanship.

Brilliant column.

Well put. Thank you.

Hmm.

I’m willing to give Williams his apparent thesis (not clearly stated).

Also I am inclined to say that editorial considerations–beginning with the headline and inserted headings–have skewed the thrust of the piece.

The so-called “I Have a Dream” speech in front of the Lincoln Memorial regurally is reduced to the last quarter of the address.

The first three quarters of the address were a truly prophetic condemnation of how politicians and theologians in the ’60s ignored the substance of the founding documents of the US. Yes, King sited the texts but his citations were stinging indictments of American history.

The juxtapositioning of King and Malcom X needs some context.

I suggest readers to take up James Cone’s stunning work, *Malcom, Martin, and America.* Cone’s brilliant analysis of the two most pithy critics of the US in the ’60s and beyond.

Were King (or Malcom) still with us I think their critiques of contemporary Christian nationalism would be withering.