For most of the twentieth century and beyond, the secretaries of state crafting American foreign policy were the sort of people that G. K. Chesterton had in mind when he said that America was a “nation with the soul of a church.” The secretaries of state believed in the democratic creed of that church with the zeal of an evangelist, and they thought their mission was to spread the gospel of democracy around the world.

These evangelists for democracy included people like John Foster Dulles, the Presbyterian-turned-Cold-Warrior who opposed international Communism as President Dwight Eisenhower’s secretary of state with the same zeal with which he had promoted the cause of global Christianity as a lay leader in the Federal Council of Churches. They included people like Madeleine Albright, who made the promotion of international human rights her chief mission as President Bill Clinton’s secretary of state – and who convinced Clinton to intervene in Bosnia in order to stop a genocide.

The list could go on. There was George Marshall, the secretary of state under Truman who gave his name to the Marshall Plan to rebuild Western Europe after World War II. There was Dean Rusk, who tragically failed to see the problems with a military commitment to South Vietnam in the 1960s but who was a fervent believer in the Cold War “domino theory” and in the principle that the United States had a duty to intervene around the world to protect against Communism. And then there were national security advisors who shared this same zeal for promoting international democracy and the American ideological mission – people like Zbigniew Brzezinski, who pushed the Carter administration to take a harder line against the Soviet Union because of its human rights abuses, or Condoleezza Rice, who helped orchestrate the War on Terror after the attacks of 9/11.

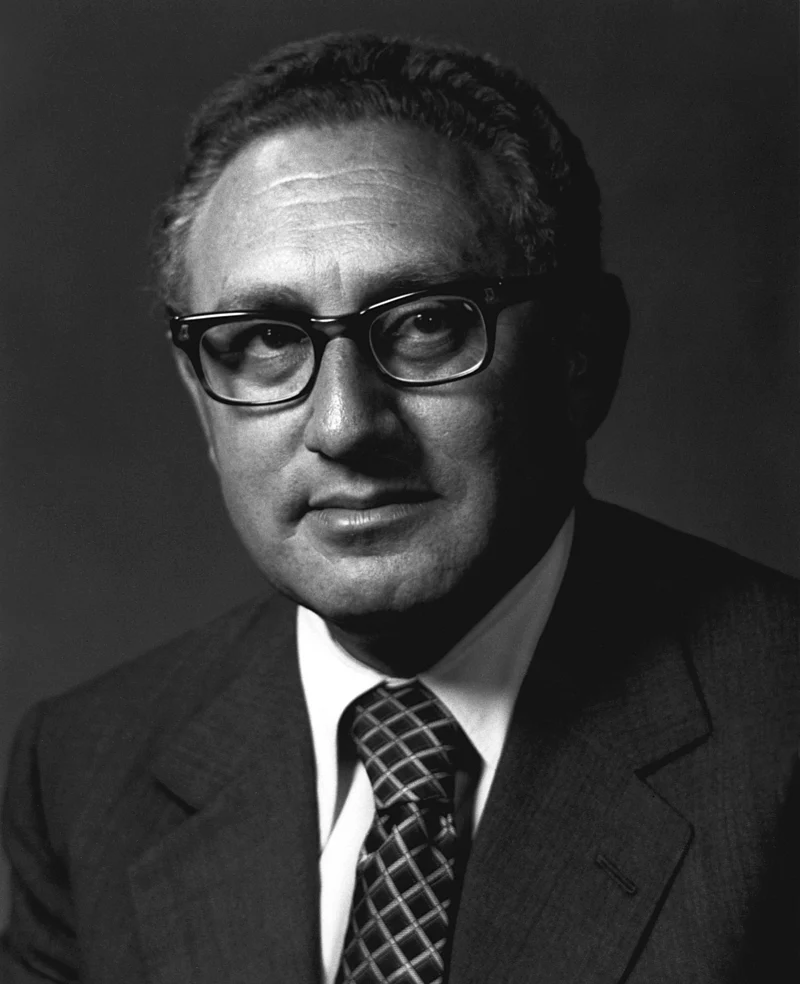

But there was one notable exception: Henry Kissinger. Kissinger did not believe in the American ideological mission, because he distrusted all ideological missions. Unlike most of his predecessors or successors, he was not interested in promoting democracy around the world, and he was far less interested than they were in fighting Communism.

Kissinger believed in only two things: power and stability. In his view, they were both intertwined.

Most of the vilifications of Kissinger that have been published in the few hours since his death have focused on Kissinger’s love of power and his ruthless exercise of it. Kissinger, unfortunately, left himself open for plenty of criticism in that regard. As a Machiavellian of the highest magnitude, he rose to the heights of power through a combination of flattery, manipulation, and exploitation. He treated everyone around him as a tool to serve his own ends. Women were a “hobby,” he said – and as a divorcee with no long-term romantic commitments, he delighted in showing up to each White House dinner with a new Hollywood star in tow, ready to be exchanged for someone else at the next event. Staff members were there to serve his interests by working 14-hour days – and he screamed at them when they failed to meet his expectations.

Ultimately, he succeeded in beating President Richard Nixon at his own game. Though he had supported one of Nixon’s rivals in the 1968 Republican presidential primaries and had said that Nixon was “unfit to be president,” he won Nixon’s favor by a combination of flattery and intelligence. He stroked Nixon’s ego by constantly praising him to his face and capitalizing on his paranoia of others. Behind Nixon’s back, though, he derided him as a “meatball mind” and called him “our drunken friend.” Both Nixon and Kissinger believed they were outsmarting the other and using him for their own purposes. But in this play for power, Kissinger seems to have won more than he lost. It was Kissinger, after all, who was the chief architect of Nixon’s policy of détente with the Soviet Union and his visit to China.

For all previous presidents, whether Democratic or Republican, an arms limitation treaty with the Soviet Union had been unachievable and a visit to China was unthinkable. Cold War ideology was too important to them to simply cast aside in order to pursue a closer relationship with the world’s two largest Communist nations.

But Kissinger was not an ideologue; he believed solely in a balance of power. And so, he engineered a foreign policy where Nixon did the unthinkable: He became the first president in American history to travel to China and the first president since the beginning of the Cold War to secure a strategic arms limitation agreement with the Soviet Union. The era of détente that Kissinger ushered in enabled Gerald Ford to become the first US president in over thirty years to preside over a nation that was not engaged in an active military conflict.

Kissinger could break with American precedent to such a remarkable degree because, unlike his predecessors, his formative years were not spent in the US; they were spent as a Jew in Nazi Germany. His entire outlook was shaped by his childhood experience of fleeing to the United States to escape German anti-Semitism.

Some might have reacted to such an experience by becoming champions of American freedom and democracy, but Kissinger instead reacted by engaging on a lifelong quest to secure international stability through a balance of power. Hitler’s rise to power in Europe had been possible only because of a breakdown in European international relations, Kissinger thought. From 1815-1914 – nearly a century – Europe avoided major wars because the power of the five empires that controlled Europe (Britain, France, Austria, Prussia, and Russia) was more or less evenly balanced, thus preventing the rise of another Napoleon (or a future Hitler).

When there was no balance of power, ideologically driven regimes with authoritarian rulers would be free to wreak havoc – and that must not happen. Previous American presidential administrations had sought to prevent authoritarianism by promoting American democratic ideology around the world in the belief that this was the answer to the world’s problems.

Kissinger, on the other hand, thought that the answer was a balance of power. He wrote about this as a Harvard graduate student, promoted the idea as a professor of international relations, and then sought to put the idea into practice as Nixon’s national security advisor and then secretary of state.

He sought to play powers off of each other – even if the countries involved were guilty of heinous human rights abuses. That was the price of international stability, he thought – and ultimately, stability was the only way to prevent another Holocaust. As he once said, “If I had to choose between justice and disorder, on the one hand, and injustice and order, on the other, I would always choose the latter.”

Such a statement went against basic American instincts, which is why the next president – Jimmy Carter – directly repudiated it and made human rights a foundation for his foreign policy. Likewise, Ronald Reagan pursued a policy driven by a traditional Cold War belief that one side in the conflict was a “city on a hill” and the other was an “evil empire.” Kissinger’s refusal to see the world in moral categories, but instead to insist only on a balance of power, was anathema to those who believed that America had an international mission to defend justice and fight evil. Kissinger’s willingness to support dictatorships and turn a blind eye to genocide and other atrocities was roundly denounced, both then and now.

But I wonder if Kissinger, despite all of his cynicism about morality and American ideology, may have stumbled onto an insight that reflects both the vision of the American founders and an important Christian truth about human nature. If humans are flawed, James Madison and other constitutional framers realized, there needs to be a balance of power in American government. But Americans who have seen the logic of this principle in domestic politics often shy away from any discussion of a balance of power internationally. For Americans who believe that their country can do no wrong, the idea that the United States should seek to share power with other countries – even countries with which it is not ideologically aligned – has often seemed anathema.

But according to Kissinger, a balance of power was the only path to peace. Kissinger’s approach to achieving this was cynical, amoral, and highly problematic – not least of which was because he showed so little interest in keeping his own personal lust for power in check. But perhaps the principle behind his life was more insightful than many Americans have assumed. Kissinger was a cynic – but sometimes it takes a cynical person to show us the dangers of our own ideological conceits and remind us that even our own nation needs to be kept in check at times by a balance of power.

Daniel K. Williams is a historian working at Ashland University and the author of The Politics of the Cross: A Christian Alternative to Partisanship.

An incisive commentary on Kissinger especially the final paragraph.