Through Jon Lauck’s eyes, the Midwest really is something to see

The Good Country: A History of the American Midwest, 1800-1900 by Jon K. Lauck. The University of Oklahoma Press, 2022. 366 pp., $26.95 (paperback)

I can’t approach a book like Jon Lauck’s The Good Country: A History of the American Midwest 1800-1900 without being reminded of Thomas Frank’s 2004 What’s the Matter with Kansas? How Conservatives Won the Heart of America. Though Lauck counts Kansas among his dozen Midwestern states, he nowhere refers to Frank—unless that reference is buried somewhere among the 1,600 endnotes attached to the 204 pages of text. Still, Lauck’s book feels like an extended rebuttal of Frank.

Frank directed a jeremiad at his home state, and by extension the Midwest and America. It was an angry, jaundiced tale of manipulation, betrayal, lost virtue, all culminating in a decade of Enron, Walmart, and George W. Bush. Tracing the change from a region known for its anti-plutocratic populism in the 1890s to the reddest of the red states by the twenty-first century, Frank’s was a tale of political and cultural calamity.

By contrast, Lauck is a booster.

Swimming against “the prevailing atmosphere of disdain and indifference” toward the region, he promises to unearth “a remarkable world . . . a land of democratic vigor, cultural strength, racial and gender progress, and civic energy—a Good Country,” a place “worth recovering, for the sake both of the accuracy of our history and our own well-being.” For a century the Midwest “constituted the most advanced democratic society that the world had seen to date.” Lauck argues that the other regions of the U.S. (and the world) were more brutally racist, more inappropriately aristocratic, more deeply plagued with inequality, and just plain less neighborly.

Since Lauck wraps up his tale in 1900, just as Frank is beginning his, it’s possible to imagine reconciling their takes. Once it was like the former, but now it’s like the latter. But I don’t think Lauck is interested in cohabiting. He celebrates the much-discussed dullness of the region as a healthy affection for “the reassuring rhythm and rituals” of hard-working, practical communities too focused on mutual aid and unflagging cheerfulness to have time for “modernity’s corrosive cynicism.” Like a more innocent Gordon Gekko, Lauck steps to the mic and announces, “Square is good!”

When I found out I’d be moving to the Midwest some decades ago, a neighbor whose business often took him to the town where I settled got quite excited: “Oh, you’re going to like it there! Lots of fast-food restaurants to choose from!” Lauck has a similar liking for the culture of the people. “Democracy walks unchecked,” he quotes one observer approvingly. “No one puts on airs.” Midwesterners like going to church; they value education; they enthusiastically plant trees on Arbor Day. “Fishing and hunting were also commonplace . . . Country fairs were common.” Lauck heads the imaginary mob of skeptics off at the pass, granting that last four-word sentence its own endnote, containing three citations. At any rate, Midwesterners read home-grown journals such as Successful Farming and Better Homes & Gardens. Lauck leaves unmentioned that Wonder Bread is a Hoosier innovation, perhaps because it came after World War I.

The author is not especially prone to personality sketches, conflict, or even narrative, so the first three chapters are a slow read. He likes offering lists of the various things Midwesterners were doing in the nineteenth century, such as planting, studying, playing sports, debating, reading, voting, and so forth—only with all the details filled in. He tells you what magazines they read (the usual ones read in the rest of America), what sports were most popular (baseball and football, like in the rest of America—basketball had yet to be invented), what classes they took (the usual ones taken in the rest of America). Ralph Waldo Emerson’s message of optimistic striving was popular; Abraham Lincoln was revered; stirring English tales of knightly derring-do fired young imaginations. Most if not all of this was just America at that time, of course, but an intangible sense is conveyed that yes, in the Midwest we may be looking at basic-common-denominator America—but even more so.

Middle America here is like Middle America elsewhere, but if the Midwest had anything special about it in the nineteenth century, it’s that Middle America is all there was. Writers, artists, and musicians, for example, almost always high-tailed it for one of the coasts as soon as they could.

While Lauck’s and Frank’s dueling analyses don’t really conflict because of the different chronological foci, it’s nearly impossible not to be nagged by the question, What in the name of all that’s annoyingly proper happened to this place since the days when smiling rosy-cheeked college boys painted the neighborhood widow’s fence, refused to let her pay, encouraged the youngsters toward self-improvement, debated the respective merits of James Whitcomb Riley and Booth Tarkington over lemonade, and were in bed by 9? The question isn’t addressed head-on. Indeed, I get the impression that Lauck believes it’s all still there, somewhere, we just need to scrape off a few decades worth of cable television, gangster rap, and casino billboards to find it.

Moving to the Midwest for graduate studies in the waning hours of the Reagan administration, I knew nothing of the region. I’d lived most of my life in the Northeast, with lengthy sojourns in Colorado, Texas, and Arizona. The Midwest was drive-across country to me.

To prepare for the move—in addition to reading Sherwood Anderson and Sinclair Lewis—I subscribed to the newspaper of my soon-to-be home. One story caught my eye. A couple had called the police on some neighbors who were displaying a U.S. flag in such a way, they said, that it “looked hippie” (they had tacked it flat against the back wall of their porch). That’s interesting, thought I. To be worried that Haight-Ashbury was mounting an incursion on Hoosierville at this late hour of the republic (this was, after all, during 40’s presidency)? And to call the police? Over the American flag? It all seemed a bit . . . colorful.

The contractor who rehabbed the house I bought was incredulous when I asked him if he lived in town: “Are you kidding?! I don’t own a gun!” A politically liberal Catholic priest leaned in sotto voce when he heard the location of the house: “You know, that’s a transitional neighborhood.” I suppose most people would call it “diverse.”

Attending a get-to-know-you potluck soon after moving, my wife brought hummus and pita bread. No one touched it. Years later, someone who was there told me, quite seriously, “We were scared of it.”

Just a few weeks ago my daughter and her neighbors witnessed a nonviolent but tense altercation between some apparently Hispanic young people in a park across the street from them. The husband of the retired couple next door tucked his pistol in his pants and stepped outside, glaring at them until they left. His wife remarked to me, “I’ve been watching Ozark, and they looked to me like they were cartel.”

An auto-dealer was going to make an exception to his policy and allow me to have my mechanic look at the used-car he was selling. He found out I worked at a Christian college. “Since you’re a Christian, I’ll let you,” he said. I smiled, then thought about it. “So if I was Jewish, you wouldn’t?” He stared at me like I had just done something rude. I declined his offer.

You don’t need a lot of time here to conclude that this place was just waiting for Donald Trump.

When I think of the Midwest, I think of a lot of things, some of them positive—the politeness of audiences at concerts, for example. But I also think of dozens of small incidents like those described. Am I being unfair? Is the Midwest all that different from the Northeast I grew up in? My loose unscientific impression is that things are a bit whiter here outside the urban areas than in other regions, and cities are regarded somewhat more fearfully.

There’s plenty of prejudice and racism all around the country, of course. I suspect Midwesterners might just have less experience navigating diversity. So they speak their minds in ways folk elsewhere would not. In other words, on a moral scale I don’t for a minute think there are any notable differences. But people behave differently. The homogeneity of the social realm means there’s less chance of argument. People here like to get along; they nod a lot.

In early 2008, before the Tea Party and before the birth certificate hysteria, the thing you heard several times a day about Obama was that he was “some guy from the streets of Chicago.” Seniors chanted it at me, young people repeated it, everyone seemed transfixed by the formula. It was intoned knowingly, as if the speaker were revealing something decisive, something darkly momentous, redolent of an exotic criminality. “You get what I’m saying?” the tone said. Lauck helpfully explains that rural folk in the Midwest regarded cities as dangerous and alien, and that “a frequent target of concern was Chicago.”

When the Ku Klux Klan sprang to life early in the twentieth century with its abhorrence of all that was immigrant, urban, and other-than-Anglo-Saxon, it found the soil well-prepared in the Midwest, Indiana in particular. When the Klan died, the fields where it had thrived remained. They didn’t all run to join Jesse Jackson’s Rainbow Coalition.

Lauck deals realistically and responsibly with the racial shortcomings of the region, but even here his determination to find a silver lining—evidence of progress—carries him away. The region’s “abolitionist energies” surely were evident, but was it really the GOP’s (excuse a little pedantry from your historian reviewer as he notes the Republican Party wasn’t the “GOP” yet) “aggressively advocating Black rights” that led to Lincoln sweeping the region in 1860? Lincoln was very far from being an abolitionist in 1860. Had he been, he would not have swept the region (49% of Hoosiers voted against him as it was) or been elected. His promise of preserving the West as free-soil (thus keeping it open to expatriating Midwestern farmers’ sons) as well as his enthusiasm for Henry Clay’s plan to colonize free Blacks in Africa were the popular parts of his appeal.

Lauck’s final chapter on “The Age of Mild Reform” takes on the Populists and others, and while nicely handled, doesn’t reveal many surprises. These reformers were also nostalgists, captivated by the idea of resurrecting a world “dominated by the centrality of Christianity, personal character, small farms, small businesses, main streets, and old-style professions.” A significant percentage of the population never disenthralled themselves. No wonder, then, that this nostalgia has curdled into an angry nationalism and an at times absurd parochialism. Politicians just to the north of me speak not of “Michigan values” but about defending “West Michigan values,” which are, apparently, under siege. I can’t imagine what those are, and they don’t specify, but it resonates with the voters. The much-ballyhooed localism that, to many I’m sure, means a trip to the farmers’ market on Saturday morning, looks a lot like the same old petulant insularity in the realms of politics and culture.

In his conclusion, Lauck relates again the uplifting example of the “old Midwest” and its usefulness for today. It might, he says, even “bolster our spirits, provide a light, and help guide us out of the current darkness and loneliness and cynicism.” Allow me to comment: No. It’s gone. Even the contemporary Midwest isn’t especially captivated by most of the things Lauck considers essential to its past virtues. When was the last time you heard anyone use the word “pluck” to describe an admired character trait? In that change, it’s just like the rest of America. The acids of modernity have had their way with the region, for good and for ill, even if maybe less so than on the coasts.

What the Midwest has bequeathed to us, Lauck completely fails to mention—an odd but telling omission. President William McKinley, a devout Ohioan Methodist, revived the war fever the region had periodically indulged, usually directed at Indians and Southerners. But in 1898 McKinley, in an American first, pointed it outward across the seas. That fever keeps getting revived, and when it does the Midwest responds with unfeigned enthusiasm. A church nearby had on its sign, early in the war on terror, “USS Battleship [Name-of-Church], At Your Service, Mr. President!” Why things are this way is a fascinating question, begging for an answer. Maybe in the next book?

John H. Haas teaches U.S. history at Bethel University in Indiana

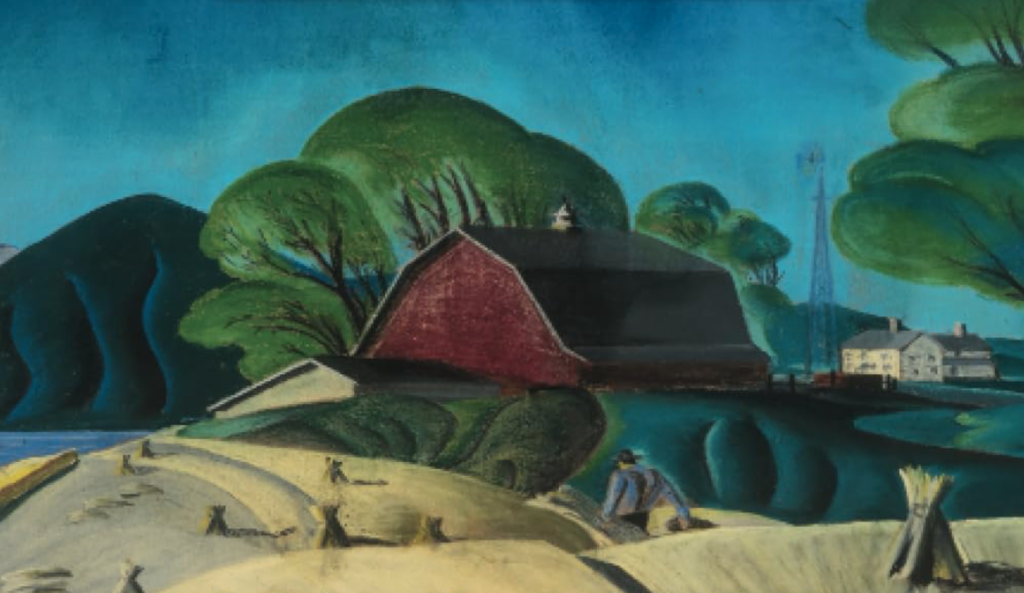

Image courtesy University of Oklahoma Press

If an academic from the Northeast moved anywhere else in the world – let’s say Brazil or Korea or Nigeria, for examples – one cannot imagine them ever writing this kind of a take-down of the values, character, and culture of their new home. I wonder why disdain for the Midwest is in a different category.

To Timothy: Because, those regions seeming slightly more exotic to a foreigner, the observer would be more likely to be captivated by a certain romanticism?

However that might be, one would hope that the mere foreignness of any given place (Russia now–or segments of it–for example) wouldn’t completely overwhelm our hypothetical observer’s capacity for honest assessment.

If you moved to Nigeria, and brought Jell-O to a potluck, and no one ate it, and you later learned they were afraid of it, you would not see that as an example of how ignorant their culture is, but rather of how much more you still had to learn about their culture.

Er, isn’t *Chicago* also the Midwest? A description of a region that leaves out many, if not most, of the region’s residents is decidedly odd.

Timothy: The good news is, I think, we are largely in agreement. You and I both agree that an apparent aversion to new culinary experiences (in an individual or a culture) might be significant and worth exploring, and we both agree that expressing fear of a food item that has been brought to a friendly gathering by someone whom no one has reason to believe is an assassin is also interesting. We disagree, however, on what that attitude might mean. You use the word “ignorant,” which actually might be applicable in its literal, non-pejorative, sense, but only if it fits (ie, if the people in question on fact don’t know anything about the food in question). I would probably use a term like “unadventurous,” or maybe just “conservative.” But that’s a judgment call.

I’m truly grateful for your willingness to engage with my comments, John. I think I have now expended my 15 minutes of fame on this thread, but I look forward to reading any other comments that are posted here. Happy Thanksgiving to everyone!

I appreciate your push-back, Timothy!

John, I loved it. We just spent two weeks in Iowa and your descriptions seem right on.

Thanks Ron. I’ve never spent any time in Iowa, and I suspect I’m going to make it all the way to the other end without doing so, too. Now I feel a little better about missing it …

John, lmao!