I write a lot about education, specifically the value of a sound liberal education (see here, for example). There is certainly no shortage of defenses of liberal education in book and essay form. In what is, perhaps, an example of the siloing of American life, I constantly see arguments on the moral imperative of expanding liberal/classical education, but such arguments seem to have little to no effect on actual educational establishments. Defending liberal education has the feeling of playing tennis against the wall: you engage in lots of activity while accomplishing nothing. Promoting liberal education reminds me of one of my favorite Willie Nelson songs: “You’ve no need to fear it/Cause no one will hear it/Cause sad songs and waltzes/aren’t selling this year.” Ditto liberal education.

Yet, recent events seem to cry out for a massive revival of liberal education. When one sees the rise in anti-Jewish rhetoric and violence, one does start to wonder if “it can happen here.” Imagine a member of Congress engaging in eliminationist rhetoric regarding Jews, and the vote to censure her is actually kind of close. University professors at our most elite institutions speak openly about how exciting they found the massive slaughter of Jews during the October 7 pogrom. The editor of the Harvard Law Review commits violence against a Jewish student. A Jewish man killed at a protest in California, while a woman in Indiana purposefully crashes her car into a Jewish day school in an attempt to kill Jewish children. The children were saved only by the woman’s incompetence. She drove into the wrong building. Perhaps the coup de grâce was the incident at the Cooper Union in New York, where Jewish students, trapped by protesters in a locked room in the library, were told by staff they could hide in the attic. In America. In 2023. We are telling our Jewish citizens to hide in the attic.

In Canada, Medical Assistance In Dying (MAID) is expanding, encouraging more and more people to just go ahead and die. In the United Kingdom, judges demand a sick baby die, despite her parents wish to seek treatment in Italy, with the Italians giving eager permission. In Ohio, voters pass a radical abortion constitutional amendment with the result that now in Ohio, a fifteen-year-old can’t get a piercing or go to a tanning booth without parental consent but can get an abortion without her parents even knowing. The notion that we may take human life when we find it inconvenient, imperfect, or unwanted extends its hold on the public imagination. We may be entering a new age of eliminating the lebensuwerten lebens, the life unworthy of life.

Perhaps the great neglected work of our time is Alan Jacobs’s Year of Our Lord 1943: Christian Humanism in an Age of Crisis. Jacobs presents the thought of various mid-20th-century thinkers who, as the Second World War seemed to be heading towards Allied victory, began to consider what life would look like post-war. Most important, how would the victorious West prevent the same disease that infected Germany from arising here. Jacobs considers such thinkers as C.S. Lewis, Simone Weil, Jacques Maritain, and W.H. Auden. Writes Jacobs: “The unspoken question underlying all these explorations was the same: if the free societies of the West win this great world war, how might their young people be educated in a way that made them worthy of that victory—and that made another war on that scale at worst avoidable and at best unthinkable.”

At the University of Chicago, Mortimer Adler and university president Robert Maynard Hutchins warned that an educational establishment dominated by the theories of John Dewey was inadequate to resist the threat posed by positivism and relativism. Dewey rejected “absolutes.” Jacobs quotes Leo Strauss as noting that “something deeper and weightier than Dewey was needed if one was to explain why it would be better to be dead than to be a Nazi.” The gooey relativism of pragmatist Dewey and the positivists left people “without firm moral commitments and therefore without any means of resisting the dogmatic certainties of communism and fascism.”

Education, wrote Maritain, “is not animal training. The education of man is a human awakening.” The job of the teacher, then, is “to help form young people so that when the opportunity comes, outside of school, for them to acquire intuition and love, they will be prepared to do so.” Jacobs concludes his summary of Maritain by stating, “Teachers, then, play a pivotal role in the building and sustaining of meaningful human culture: if they do not intervene in young people’s lives, in the indirect yet distinctive way that only they can, the culture will surely, if slowly, fall.” One need only look at the pathetic education our teachers today receive, especially our elementary teachers, to know how far we are from Maritain’s vision.

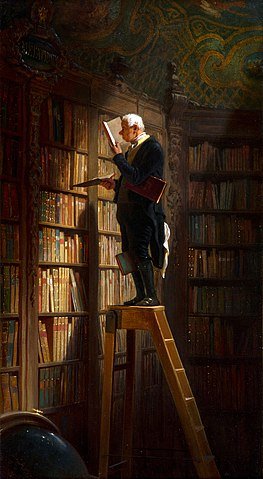

Much of education today, to draw from Auden, is not about gaining wisdom but about “graduating cum laude.” It is a technical training, designed to give students a credential that they can use to get a job. It is no accident that our most prominent antisemites and advocates for killing the unwanted and infirm are also generally among our most educated. Our schools, from first grade through doctoral programs, have concerned themselves with efficiency, productivity, and ideology. They have given up on wisdom, on the three great transcendentals: the good, the true, and the beautiful. In terms Lewis uses in The Abolition of Man, education has removed the souls of our people, filled them with ideology, and makes them fodder for the Innovators and Controllers. Why not get rid of the imperfect, inconvenient, the unwanted? They get in the way of us getting what we want. They are inefficient.

Jacobs suggests that Hutchins and Adler believed “Americans have more to fear from their professors than from Hitler, because their professors make us all more likely, over the long run, to become Hitler. Only a clearly articulated and rationally defended account of true justice can resist totalitarianism. ‘In the great struggle that may lie ahead, truth, justice, and freedom will conquer only if we know what they are and pay them the homage they deserve.’” Our education instead articulates how to get a job, how to be a good contributor to the GDP, and how to be nice to nice people.

We fail to introduce our young people to a coherent cultural narrative and then are surprised that we find ourselves polarized. It’s a sad comment on our times when comedian Bill Maher can give a more stirring defense of teaching Western Civilization than can almost all college faculty and administrators. Whether it is 1984, Fahrenheit 451, or Brave New World, our dystopian literature indicates that it only takes one generation to forget the past. If one generation isn’t taught, for instance, what makes the year 1066 important or what mistakes Macbeth made, it just disappears; they can’t pass on what they never got.

There is a rise in homeschooling and Classical Christian Education. Perhaps it is too little, too late. But perhaps, like the rebel scholars in Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, they will preserve some vestige of civilization, to be reborn when the time is right. Let’s hope there will still be someone around to pass it on to.

Great article.