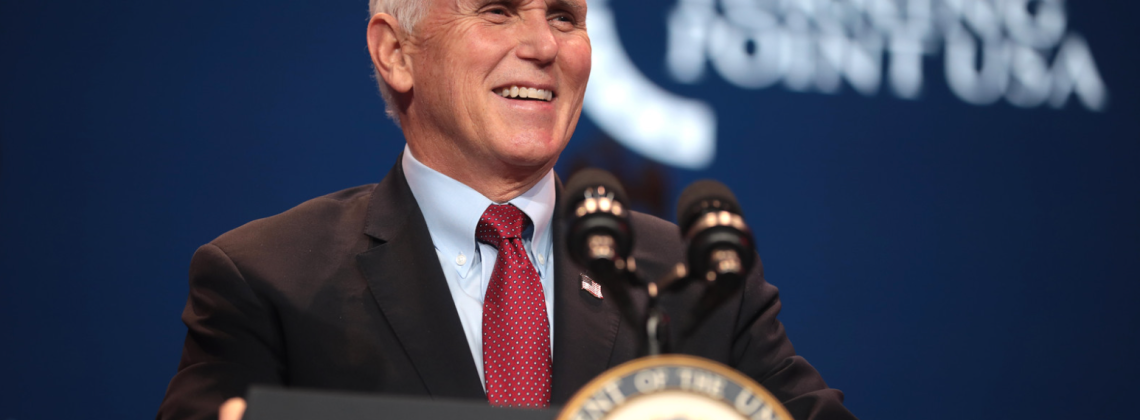

As Mike Pence discovered

For Mike Pence, the vice presidency seemed to be the perfect stepping stone to the White House. After all, during the past half-century several former vice presidents—including Richard Nixon, George H. W. Bush, and Joe Biden—used the position to win presidential terms of their own, and several others (including Walter Mondale and Al Gore) became their party’s nominee.

But Pence wasn’t able to leverage his experience as vice president to win his party’s nomination. Perhaps that’s partly because the vice presidency is a less reliable path to the presidency than many have assumed. For most of the nation’s history, a vice presidential nomination was much more likely to end a person’s political career than propel the person to the White House.

The country’s first vice president, John Adams, found the position a miserable one. After taking a leading role in writing the Declaration of Independence and representing his country on diplomatic missions to Europe during the Revolutionary War, he could not bear the irrelevancy of being vice president under George Washington. It was “the most insignificant Office that ever the Invention of Man contrived or his Imagination conceived,” he complained to his wife.

But Adams, at least, did eventually get to become president—which is more than most vice presidents have experienced.

Well into the twentieth century, the job did not train candidates for the presidency—which is why on the occasions when nineteenth-century presidents unexpectedly died in office the men who succeeded them were often unprepared to take over the duties of chief executive. John Tyler, who became president after William Henry Harrison died of pneumonia only a month into his presidency, did so much to anger fellow members of his party that all but one of his cabinet members resigned in protest. Millard Fillmore, who became president after Zachary Taylor’s sudden death, presided over the disintegration of his own party, which gave him the dubious distinction of being the last Whig ever to serve as president of the United States. Andrew Johnson, who succeeded Abraham Lincoln, alienated members of Congress who should have been his supporters and became the first president to get impeached.

Both parties repeatedly nominated political hacks for the vice presidency, largely because the position seemed too inconsequential to worry about.

By 1900 the idea that the vice presidency was the most effective method of political banishment was so well established that the Republican party bosses of New York realized that they could use it to end the rising political career of their state’s popular, reform-minded young governor: Theodore Roosevelt. They plotted to put Roosevelt on the ticket with William McKinley, knowing that if they did so his political career would be nipped in the bud and they wouldn’t have to worry about his progressive proposals, which offended some of the party’s conservative leaders.

Roosevelt was astute enough to realize what was going on, and he did everything in his power to resist it. “Under no circumstances” would he accept the vice presidential nomination, he insisted. Comparing it to the most boring, inconsequential job he could think of, he declared, “I would a great deal rather be anything, say professor of history, than vice president.”

But refusing the invitation to be vice president was harder than Roosevelt envisioned, and when the offer came, he felt compelled to accept, however much he chafed at the idea. At least one party leader, Mark Hanna, was a little worried, because even though he had wanted to end Roosevelt’s political career and realized that the vice presidency could be an effective way to do it, there was always the risk that the president might die in office. “Don’t you realize that there’s only one life between this madman and the White House?” he asked his fellow political cronies in the GOP.

Six months after Roosevelt took the job, Hanna’s worst fears were realized. After McKinley’s assassination Roosevelt unexpectedly became the nation’s new chief executive—but if it were not for that event, he might never have gotten to the White House. As it was, Roosevelt proved to be unsettling enough to old-guard Republicans that it eventually resulted in a party split when Roosevelt launched a new Progressive Party in 1912.

For the next few decades, vice presidents continued to complain about their lack of power. The job wasn’t “worth a bucket of warm spit,” Franklin Roosevelt’s first vice president, John Nance Garner, complained. Although Garner, a rival to FDR who publicly opposed some of his policies, decided that he couldn’t refuse Roosevelt’s offer of the vice presidency, he did not do so graciously. “I don’t intend to spend the next four years counting the buttons on another man’s coattails,” he groused. One headline in the Washington Herald in 1932 accurately summarized the situation that existed for more than a century: “It Just Seems Like Nobody Wants to Be Vice President.”

It was not until the late twentieth century that the vice presidency was remade into a highly coveted, consequential position. When the United States became a global power after World War II, presidents began using their vice presidents as emissaries to travel the globe and handle complicated diplomatic negotiations. They relied on their vice presidents for policy advice and political help in negotiating with Congress. Beginning with Walter Mondale (vice president to Jimmy Carter, 1977-1981), the vice president’s office was moved into the West Wing of the White House, where vice presidents could work directly with the president in all the administration’s activities.

When the vice presidency became an executive position in its own right—a position modeled less on the original constitutional mandate than on the contemporary corporate world, where powerful vice presidents act not as placeholders but as implementers of the broad strategies set by their CEO—voters began to view vice presidents as experienced leaders who might be qualified for the presidency.

But this clearly was not the case this year, at least in the Republican Party. That’s because the GOP has become an anti-establishment party in which political experience of the sort that a vice president is likely to have acquired can be a political liability.

A vice president is by definition an insider whose actions will always have to be subservient to the president—and who therefore won’t easily be able to cultivate an image as an independent executive of the sort that many voters now seem to want. For an anti-establishment party that values toughness and bravado, the vice presidency is one of the worst places one can be to launch a presidential bid.

If the vice presidency was ever able to prepare a person for a viable presidential run, it was never merely because of the title or the office itself. Instead, it was only because a vice president managed to use the office to gain the experience to convince voters that he or she was a capable, competent person who knew how the executive office functions and was now ready to lead it.

But if voters don’t value political experience or proven policymaking skills when choosing candidates, the vice presidency may once again become more of a political burying ground than a path to the White House. That’s unfortunate, since the vice presidency in recent years has become a newly important position that really does give its occupants relevant policymaking and diplomatic skills that could be useful for a chief executive.

In any case, it appears that Mike Pence may never again get the opportunity to try to convince voters that he has those skills. If his time as vice president effectively ended his political career, he’s not the first former vice president to realize the frustrations of the position. Perhaps John Nance Garner would sympathize.

Daniel K. Williams is a historian working at Ashland University and the author of The Politics of the Cross: A Christian Alternative to Partisanship.