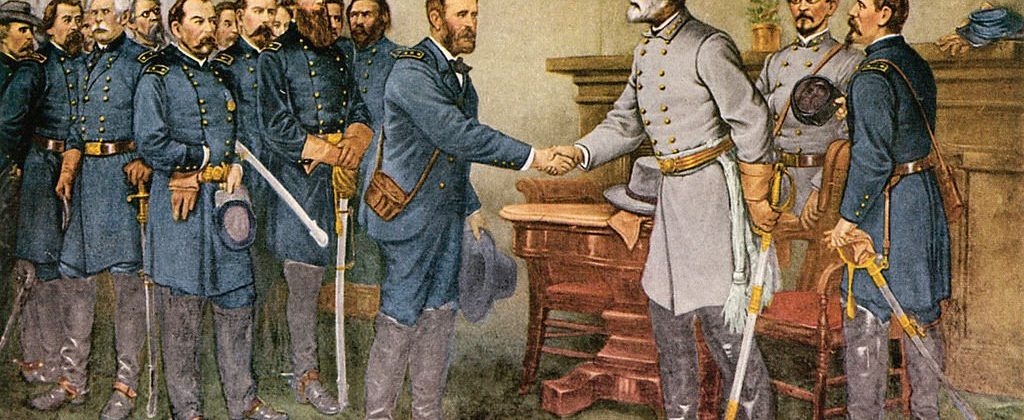

Like many with a passing familiarity with U.S. history, I was upset when I saw the Prager U video for kids about Grant and Lee meeting at the end of the Civil War. In the video, Grant says: “Lee was a good man. We had fought together in the Mexican American War. This time, we were just caught on the opposite side of things.” Of course, that is not a truthful representation of Grant’s views, not even when you’re trying to simplify it for children. In his memoirs, Ulysses S. Grant wrote:

“What General Lee’s feelings were I do not know. As he was a man of much dignity, with an impassible face, it was impossible to say whether he felt inwardly glad that the end had finally come, or felt sad over the result, and was too manly to show it. Whatever his feelings, they were entirely concealed from my observation; but my own feelings, which had been quite jubilant on the receipt of his letter, were sad and depressed. I felt like anything rather than rejoicing at the downfall of a foe who had fought so long and valiantly, and had suffered so much for a cause, though that cause was, I believe, one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse. I do not question, however, the sincerity of the great mass of those who were opposed to us.” (735)

A cause which was “one of the worst for which a people ever fought, and one for which there was the least excuse” isn’t exactly “the other side of things,” even if Grant had personal respect for Robert E. Lee and his dignity. What Prager U is doing is lying. (I’m not going to address the use of Prager U videos in school curriculum here.) This is all very troubling.

This isn’t about “going easy” on Confederates to smooth over feelings and avoid offending anyone. The actual Confederates are all dead. Nothing we say about them will affect them in any way. They don’t hear our criticism and they don’t care about it. Neither do they hear praise. You can tell the full truth about the Confederacy without offending any veterans. Or their children. And most likely you won’t even be offending their grandchildren.

If you were worried about offending Confederates, Grant understood that. Elsewhere in his memoir he wrote:

“I would not have the anniversaries of our victories celebrated, nor those of our defeats made fast days and spent in humiliation and prayer; but I would like to see truthful history written. Such history will do full credit to the courage, endurance and soldierly ability of the American citizen, no matter what section of the country he hailed from, or in what ranks he fought. The justice of the cause which in the end prevailed, will, I doubt not, come to be acknowledged by every citizen of the land, in time. For the present, and so long as there are living witnesses of the great war of sections, there will be people who will not be consoled for the loss of a cause which they believed to be holy.”

Grant understood that some would not be able to let it go. The North shouldn’t gloat. All could be respected who served. And yet, that did not mean respecting the cause of the Confederacy. In the next sentence, Grant wrote: “As time passes, people, even of the South, will begin to wonder how it was possible that their ancestors ever fought for or justified institutions which acknowledged the right of property in man.” (115-116)

We, in 2023, have no good reason for minimizing the truth about the cause of the Confederacy. Who would we be doing that for? No one has to define themselves by the Confederacy in 2023. It is an active choice, one which requires effort. And to suggest that to guarantee people dignity, past or present, we have to appreciate their causes, we make human dignity conditional and tell another lie.

What about the South? Southerners don’t have to define their culture by the Confederacy. It’s as silly to say that the South is defined by the Confederacy from the right of the political spectrum as it is from the left. In a recent video about his new album, Tyler Childers made a very charismatic appeal about identity and the South and the country. He opened by saying, “I have no soapbox to stand on to talk preachy to anyone about anything.” He addressed COVID, police brutality, riots, and the fact that “the country is feeling a general angst.” At the end, Childers suggested that feelings about the Confederacy serves as a way of dividing disadvantaged people in his region. But it need not be this way:

“We can start looking for ways to preserve our heritage outside lazily defending a flag with history steeped in racism and treason. Things like hewing a log, carving a bowl, learning a fiddle tune, growing a garden, raising some animals, canning our own food, hunting and processing the animal, fishing, blacksmithing, trapping, and tanning the hide. Sewing a quilt. And if we did things like that, we’d have a lot less time to argue back and forth over things we don’t fully know, backed by news we can’t fully trust. Love each other, no exceptions. And remember, united we stand, divided we fall.”

White Southerners have more going for them than the Confederacy. And none of them have to see their identity as defined by it. That is a choice.

When something like that Prager U video circulates, you aren’t being asked to be kind to people who lost a war. What you’re being asked to do is to apply some kind of mercy rule to the Confederacy, one where you downplay their own words and actions, where you gloss over the centrality of slavery, where you glaze over their military defeat, where you ignore the incompatibility of ‘Merica with the Confederacy. The only way to do all of that is to be dishonest about the past.

We need not get into a whole history of the Confederacy to acknowledge that many of its myths are inadequate. Too much has been made of the Shelby Foote anecdote about the rebel soldier who told a Union soldier he was fighting “because you’re here.” Where was Gettysburg fought? Was there no Southern aggression? Too much has been made of “states’ rights” without acknowledging the “right” that Confederate states were most desperate to preserve. Why was Kansas bleeding?

And though whataboutism has all the intellectual integrity of sophistry, no one is saying that the Union was perfect. But perhaps you’ve also noticed, while people still run around celebrating Bedford Forrest and obsessing over Robert E Lee, you don’t have a bunch of northern kids named Chamberlain or Ulysses. And there aren’t people who go around talking about how John Brown was actually a genius when looked at from a certain angle. Northern people are kind of ashamed of him. And plenty of people want to take down statues of Lincoln.

This isn’t just about making sure people have the “right” views of the Confederacy. This is about the kinds of actions we legitimize in our present. Many Americans saw Sound of Freedom this summer and were moved in powerful ways. They want more awareness, more action on this issue. Well, the spirit that excuses the Confederacy and its trafficking in human lives will not be the spirit to take down present-day human trafficking. People who want a better and more functional government will not find good models in celebrating those who sought to destroy the one we have. Lying about the past won’t get us anywhere good in the present.

It’s not criminal to love the Confederacy. But it is a choice and should be regarded as such. We don’t have to “go easy” on the facts of history for the feelings of any Civil War participants. They exist in a distant past. Those in the present who take up their cause do so willingly. If the truth is uncomfortable for them, that cannot be helped.

Faulker wrote that “the past is never dead. It’s not even past.” We build our understanding of the present on the past and we draw from the well of the past when we imagine tools for the present and alternatives for the future. In that context, a little lie is a dangerous thing. With regard to all of the past, U.S. and other, we can turn to a Southern saying: Tell the truth and shame the devil.

Nicely done.

I’d like to put some nuance to “it’s a choice.” We grow up in an environment that we take for reality. Others have made choices that we see as normative. I didn’t choose to be a right wing Republican. That is what my parents and grandparents were and I picked it up from them as God’s way. In my college years I was exposed to other ways of thinking. Then I had a choice to make. And a choice going against my upbringing meant conflict within the family. The easiest way, and most likely way a person chooses to go is to stick with family tradition. Then when that “choice” is taken you end up with better family life and most likely fit into your community also. It is hard to break the cycle when one’s identity is tied into it.