This existential crisis is less about technology and more about morals and will

Science fiction writer Isaac Asimov proposed three laws to govern robots back in 1942. The first law was “A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.”

What if instead the first law was “For God so loved the world that he gave his one and only Son, that whoever believes in him shall not perish but have eternal life”?

I’m not actually asking whether intelligent computers have a soul, and I’m not asking whether Jesus died to save Vision of the Avengers or Data from Star Trek.

But I’m not joking. If artificial intelligence (AI) is meant as a tool for human beings—a tool that understands language and motivations in a way a shovel can’t—then what would be the ramifications of programming it with some basic assumptions of Christian theology? What if a computer began with the knowledge that only God is perfect, all humans are sinful, redemption for humans comes through the sacrifice and resurrection of Christ, and that in the world as it is, we are commanded to love one another and forgive each other?

Would computers programmed with such instructions be safer than the AIs we currently have?

Let’s start with the immediate problems: AIs have learned how to write. This is perhaps their most publicly frightening feature. They can write essays, novels, poems, and screenplays. They are generally not as good as human writers—yet. By 2025 they will be.

Writers are understandably terrified. If a studio executive can open her phone and say “Give me sixteen scripts for Deadpool 3,” then she never has to pay human writers. The Writers’ Guild of America is currently on strike over just this issue. They want Hollywood to agree up front not to use this tech.

The WGA struggle is a labor issue, a squabble over the technological equivalent of moving their jobs offshore. More Americans are unsettled, however, by the prospect that a machine can replicate human mental efforts rather than human physical efforts.

But there is another aspect to AI’s mastery of language: theft.

In order to learn how to write, language AIs read thousands upon thousands of texts. They learn to write the way they learn to play chess—by analyzing billions of possible moves and selecting good ones. Human beings don’t do that; we interact with the world before we know what language is.

In other words, an AI cannot have human experiences on its own. Everything it produces came from a human writer at some point. And tech companies force-feed AIs thousands of texts. In other words, all the text computers use to generate written material is taken, piece by piece, from other writers. It is not created in a spontaneous act of creation. That’s fine when those works are in the public domain, but not when those works are under copyright. Writers are having their work monetized by AI companies without even knowing it—part of a general trend towards simply assuming that creative work is free. A recent effort by an AI company to write a new Drake song did not even ask Drake if they could. They just stole his stuff.

The current national debate on this topic boils down to “You can’t let computers take my job” versus “Why can’t computers write our novels? They already order my latte.” Most of our current discussion of AI is funneled through economics: I must do what is efficient; otherwise I will lose money.

A Christian AI might say: “It’s wrong to steal.”

Theft is, of course, explicitly forbidden multiple times in the Bible. But there is a deeper Christian theology here: We are commanded to love one another. Is it loving to eliminate jobs in the name of efficiency? Is it loving to offload human creative tasks—the things that make us human—to machine minds and then market them?

And what about when an AI is instructed to make morally objectionable content—when an AI is ordered to write material that is racist, violent, or sexually explicit?

Deepfake technology can now create custom pornographic videos of anyone. People’s faces are now appearing in adult films without their consent or participation. There have been efforts to control this by ChatGPT (the largest open AI) but—surprise—people on Reddit have worked hard and found ways to compromise the safety protocols.

Christians may disagree about whether Jesus would want humans to take off their clothes and videotape themselves engaging sexual activity. They would certainly object to someone’s image or voice being used in a digital reproduction of such an act without consent.

The dilemma is very similar when dealing with the use of deepfakes by political actors, which we will see throughout 2024.

Christians are not alone in these moral qualms. Muslim, Hindu, and atheist programmers (among many others) would and should ask the same questions. The point is that for many years the moral implications of technology have been laughed out of the public sphere because it has been assumed that what is economically efficient is also socially good.

This is not true. And if I was asked why economics should not guide our social decisions, I would point to the teachings of Jesus Christ.

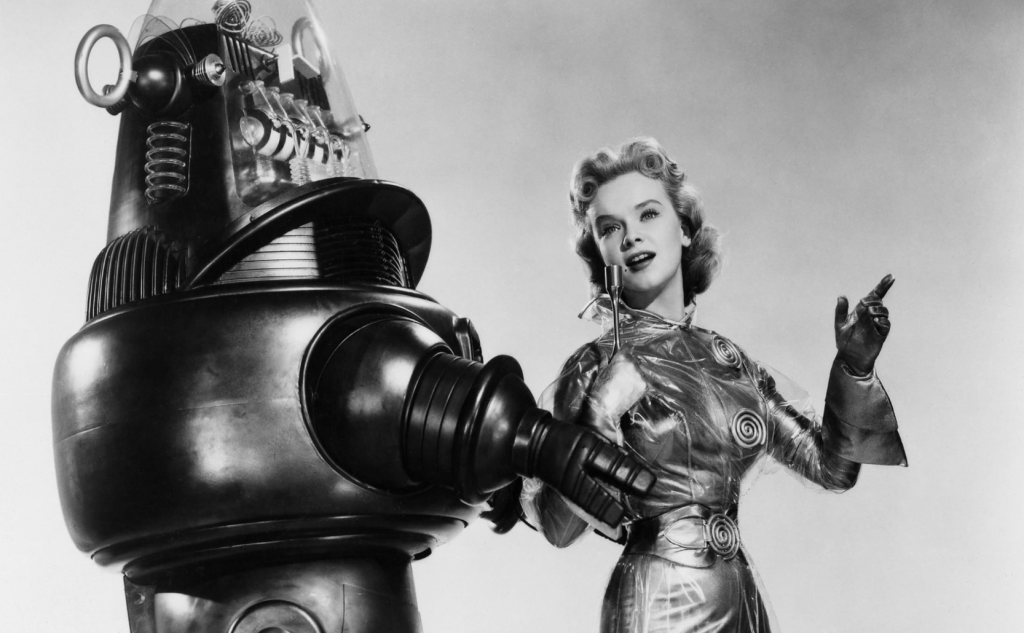

There is a lot to fear about AI. Some of the programs don’t seem to be working the way we expect them to, and almost no one wants machines thinking for themselves. (We love Data, but we fear Skynet.) This will need to be the province of the government; the European Union and the Department of Defense have made strides in this arena, but the U.S. government has not.

In the meantime, many of us are frightened not just by what the technology does right now but also by the fact that so many people have access to it. And the AI will do what it is told. So if studio executives want AI to write Saw vs. Transformers, an AI will write Saw vs. Transformers. If Reddit users want to make ChatGPT write erotica, ChatGPT will write erotica. If an AI can do it, it will do it.

An AI is as sinful as its user. Christianity says everyone is sinful.

Thus, the case for a Christian AI: a machine that understands that humans are sinful, that makes love and forgiveness its central tenets, one that talks about the resurrection rather than engage in hateful memes on Twitter.

I don’t necessarily want to build this AI. There are obvious problems: Some Christian nationalists think that loving God means controlling the government, shooting non-believers, or stoning people for having sex before marriage. A millennial Christian AI would be way less likely to condemn homosexuality than would a Boomer Christian AI, to say nothing of whether we want Catholic, Calvinist, Wesleyan, or Pentecostal AIs as well.

What I do want is for folks to recognize that the issue of AI is not grounded in tech. You do not need to design a Christian AI, because an AI is (as of now) still an extension of its user. If we want a loving and compassionate AI, we must be loving and compassionate.

We need fuller regulation over AI for the same reasons we have regulation over opioids and nuclear material. But you, personally, are still capable of being aware when you are using AI and to what ends you are using it. Suggestions on Christian use of AI can be found here and here.

In the end, it is not an issue of tech. It is a matter of how far we will go to live as Christ lived.

Adam Jortner is the Goodwin-Philpott Professor of History at Auburn University. He is the author of The Gods of Prophetstown and the Audible original series American Monsters.

Image credit: MGM, Robby Robot from “Forbidden Planet” (1956)

This essay is really thoughtful, Adam! Thanks for making me stop and think this morning.