“Whenever I am in Southwold, the Sailors’ Reading Room is by far my favourite haunt. It is better than anywhere else for reading, writing letters, following one’s thoughts . . .”

In Book Marks, an occasional feature at Current, we take fresh cuttings from old books (or about old books). They may often be about writing, education, communication, and the life of the mind generally, though we reserve the right to snap a sprig of greenery that simply tickles the fancy.

Why look at old books? Because there’s a slat loose in the fence they’ve got us penned up in, and we can jiggle it free to see better what’s going on out there.

With each extended quotation we offer an orienting comment, but that’s not where the action is. The question is whether the words of those who have gone before may speak to you.

*

You’d never know it from the title, but The Rings of Saturn is about a walking tour of East Anglia, the historically important but by the early 1990s decidedly down-at-heel country lying low along the North Sea coast of England. Or is it? From one mile-long, rambling sentence to the next, you never know what its author W. G. Sebald is going to be talking about. This is stream-of-consciousness literature par excellence, with an unstoppable logic connecting each leg of the journey to the next.

Nevertheless, I was briefly tempted to break up the following quotation into two or three paragraphs out of solicitude for you, dear web reader—but no, that would not do. Paragraphs would deny you one of the signature marks of Sebald’s writing (and I’m told the German prose is if anything even more relentless). So take a deep breath and step on into the flow.

Hear what he has to say:

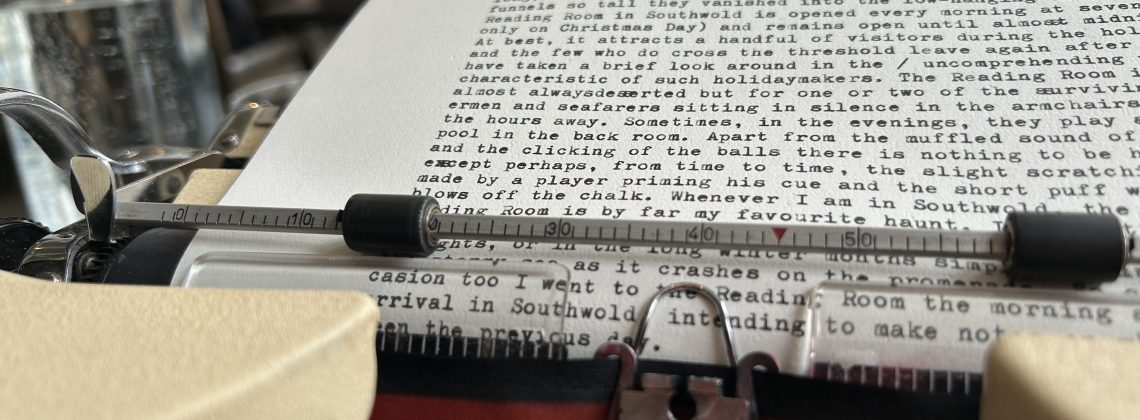

Now, with an advancing chill in the air, I sought the familiarity of the streets [of the town of Southwold] and soon found myself outside the Sailors’ Reading Room, a charitable establishment housed in a small building above the promenade, which nowadays, sailors being a dying breed, serves principally as a kind of maritime museum, where all manner of things connected with the sea and seafaring life are kept and collected. On the walls hang barometers and navigational instruments, figureheads, and models of ships in glass cases and in bottles. On the tables are harbourmasters’ registers, log books, treatises on sailing, various nautical periodicals, and several volumes with colour plates which show legendary clippers and ocean-going steamers such as the Conte di Savoia or the Mauretania, giants of iron and steel, more than three hundred yards long, into which the Washington Capitol might have fitted, their funnels so tall they vanished into the low-hanging clouds. The Reading Room in Southwold is opened every morning at seven (save only on Christmas Day) and remains open until almost midnight. At best, it attracts a handful of visitors during the holidays, and the few who do cross the threshold leave again after they have taken a brief look around in the uncomprehending way characteristic of such holidaymakers. The Reading Room is thus almost always deserted but for one or two of the surviving fishermen and seafarers sitting in silence in the armchairs, whiling the hours away. Sometimes, in the evenings, they play a game of pool in the back room. Apart from the muffled sound of the sea and the clicking of the balls there is nothing to be heard then, except perhaps, from time to time, the slight scratching noise made by a player priming his cue and the short puff when he blows off the chalk. Whenever I am in Southwold, the Sailors’ Reading Room is by far my favourite haunt. It is better than anywhere else for reading, writing letters, following one’s thoughts, or in the long winter months simply looking out at the stormy sea as it crashes on the promenade. So on this occasion too I went to the Reading Room the morning after my arrival in Southwold, intending to make notes on what I had seen the previous day. At first, as on some of my earlier visits, I leafed through the log of the Southwold, a patrol ship that was anchored off the pier from autumn of 1914. On the large landscape-format pages, a fresh one for each new date, there are occasional entries surrounded by a good deal of empty space, reading, for instance, Maurice Farman Bi-plane N’ward Inland or White Steam-yacht Flying White Ensign Cruising on Horizon to S. Every time I decipher one of these entries I am astounded that a trail that has long since vanished from the air or water remains visible here on the paper. That morning, as I closed the marbled cover of the log book, pondering the mysterious survival of the written word, I noticed lying to one side on the table a thick, tattered tome that I had not seen before on my visits to the Reading Room….

— W. G. Sebald, The Rings of Saturn (1995; trans. Michael Hulse, repr. New Directions, 2016), pp. 92-94

*

Jon Boyd is keeper of Book Marks at Current. He is associate publisher and academic editorial director at InterVarsity Press, the saxophonist in an improvisational rock band, a user of mechanical typewriters and postage stamps, and (with his wife and daughters) a resident of the City of Chicago.

Gotta love a sentence like this:

On the walls hang barometers and navigational instruments, figureheads, and models of ships in glass cases and in bottles. On the tables are harbourmasters’ registers, log books, treatises on sailing, various nautical periodicals, and several volumes with colour plates which show legendary clippers and ocean-going steamers such as the Conte di Savoia or the Mauretania, giants of iron and steel, more than three hundred yards long, into which the Washington Capitol might have fitted, their funnels so tall they vanished into the low-hanging clouds.