In the course of teaching college classes, I encounter all kinds of readers among my students. Some don’t like to read, some love to read. Some are overly accepting of everything in print. Some are the opposite. Occasionally, a student will use a single sentence to dismiss an entire book—one phrase they’re not sure they agree with is enough to write off an author. Obviously, these students are not alone. Sometimes just the setting of a book seems to be enough to make people reject it—as we see with the recent Elizabeth Gilbert incident.

In the twelfth century, the Jewish philosopher Maimonides wrote The Guide of the Perplexed. It’s a book for a young man who was torn between what he perceived as a conflict between religion and reason. He was wondering how to reconcile his life according to religious dictates with his understanding of the world and with the philosophy that surrounded him. At the beginning of the book, Maimonides made a request of his readers:

I implore every reader of this treatise in the name of God Almighty not to interpret even a single word of it to anyone else unless it clearly agrees with the opinions expressed by former authoritative writers on our Law. If he understands any of it in such a way as not to agree with the views of my illustrious predecessors, let him not so interpret it to others, nor rush into disproving me, for it may well be that he has misunderstood my words. He would thus harm me in return for the good I wanted to do him and would be one that renders evil for good (cf. Psalm 38, 21). Nay, I ask every one into whose hand my treatise falls to study it carefully; if it relieves any of his difficulties, even a single problem that is in his mind, let him be grateful to God and satisfied with what he has understood. If he finds in it nothing of use to himself, let him forget that it was ever written. Should anything in it appear to him detrimental, I would ask him to try and find a more favorable explanation for it, even though it might seem a little far-fetched, and to give me the benefit of the doubt, as is our duty towards every man (cf. Aboth 1, 6), how much more so when it comes to our religious teachers, the bearers of our Law, who endeavor to communicate the Truth to us according to their ability.

All too often, when we’re reading, we’re looking for reasons to reject. Sometimes we’re trying to decide whether or not the author is on “our team” when it comes to ideology or anything else. Do they support the things we do? Do we agree with all of their interpretations? If not, we can dismiss the book or article. Is the author someone we like and approve of? If not, we can reject a book without even reading it.

Maimonides is asking us to read very differently. He stakes his claim to seeking a position aligned with earlier teachers of the Law, but he is also asking for kindness. If we don’t like his book, we can just forget all about it. But if it seems to be bad in some way, maybe we can try to see it differently. We can “try and find a more favorable explanation for it, even though it might seem a little far-fetched.” Maimonides is asking for, and emphasizing being, generous readers.

There might seem to be a big ask in this approach, but it can bear real fruit for readers. My students who decide a book is “bad” as soon as they disagree with part of it are rarely the ones who fully grasp the argument or understand why a book is significant. They aren’t reading to learn about the book or the author or the time period, they’re reading to accept or reject—they’re reading for affirmation of their existing beliefs. If that’s all we seek, it really doesn’t matter what we read.

What does a generous reader look like? A generous reader can, as Maimonides invites, give an author the benefit of the doubt in a grey area. Such a reader can also acknowledge disagreement and read on, to see if there is anything worth taking from the book. Such a reader can even decide it’s worthwhile to understand a book even if it offers nothing we’d want to incorporate into our views. If we can do those things, we begin to approach comprehension. We might understand why a flawed book keeps being read or referenced. We might begin to appreciate things like style and context.

A generous reader does not have to leave critical reading behind. Some books are bad. Some books could be better written and better conceived. Even a generous reader doesn’t have to recommend everything or decide that every book contains a kernel of truth or anything like that. We can legitimately warn people away from books. But we can’t fully make those judgments ourselves if we don’t do a book the justice of a real reading. A real reading requires more than a summary thumbs up or thumbs down. The same applies to our interactions with people.

The mother of one of my college friends liked to comment after receiving bad customer service, “maybe that person is having a really bad day.” Just as we typically shouldn’t reject an entire book for one sentence, it usually takes more than one interaction for us to know someone’s character. If we want to have substantive relationships with people, we shouldn’t only listen to them to decide if their views align with ours. We need to look beyond agreement or style to find quality friendships. We will do better in understanding both books and people if we can extend the benefit of the doubt without abandoning the quest for comprehension.

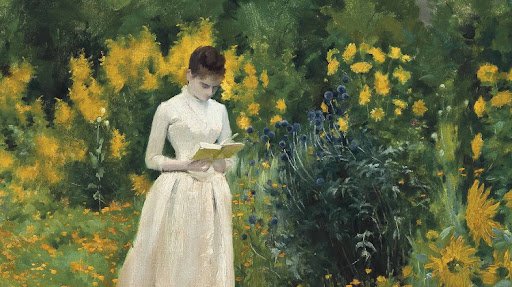

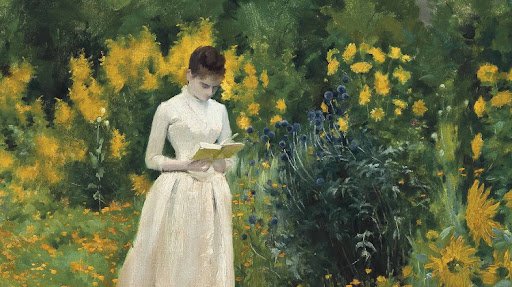

Books and people can open up new horizons for us. Both will contain some things we like and some things we don’t. Sometimes you have to turn a few pages before you really understand. Sometimes you have to consider alternative viewpoints, or at least hear them out. Encountering books as generous readers can be practice for encountering people in generous ways.

This is a wonderful reflection. So glad to encounter this Maimonides quotation for the first time. I tell my students that when you read a book the author can’t learn from you, but you can learn from them, so if all you end up doing is scolding them for not holding a view you hold then no one is learning anything. Again, of course, there are some authors that we can’t learn from – or shouldn’t learn from because we would be learning something pernicious – but usually we can still know that we are right about what we know but also learn something worthwhile that they know.