In 2007 I took a trip to the United Kingdom. Toward the end of the trip, I found myself in a small used bookstore in a quaint Scottish village. Needing something to read on the plane ride back, I spotted a copy of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone (published in America as the Sorcerer’s Stone). I knew my wife had a copy at home, but the reasonable price justified the redundancy. While my wife had read every Potter novel published up to that point (every book but what would be the last, The Deathly Hallows), I hadn’t read any of the books. Not for any particular reason. I had basically dismissed the books as another teen passing fashion, like hula hoops, New Kids on the Block, or swallowing Tide pods. Still, looking for a breezy airplane read, I decided to give the ridiculously popular book a chance.

I started and finished the book on that plane ride with time enough to watch the film Wild Hogs (an hour and a half of my life I will never get back). This is partly a testament to the book’s length—it’s fairly short—but also to its readability. Sure, it is a book pre-teens can read, so it’s not exactly an intellectual challenge, but Philosopher’s Stone is also a ripping good read. Arriving back home I faced a fateful decision. The newest and reportedly last book, the aforementioned Deathly Hallows, was set to be released in a matter of weeks. Do I attempt to read the other five books before its publication so I could take full advantage of the release event, or should I just let it go? I chose the former.

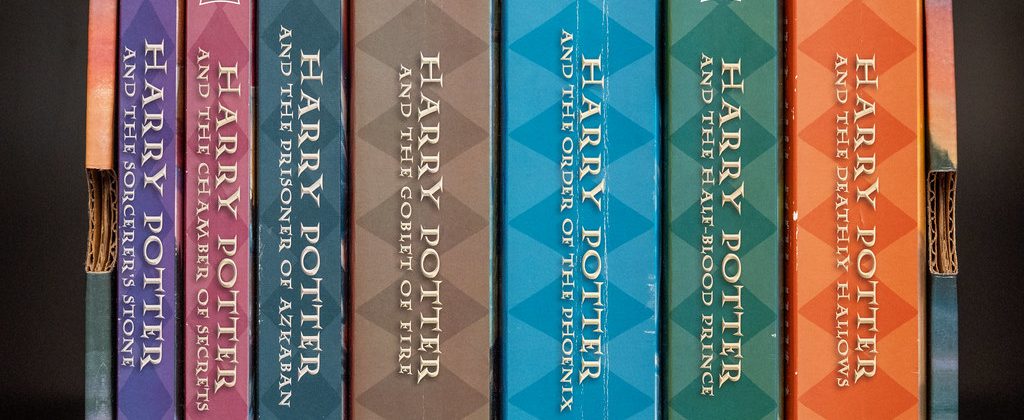

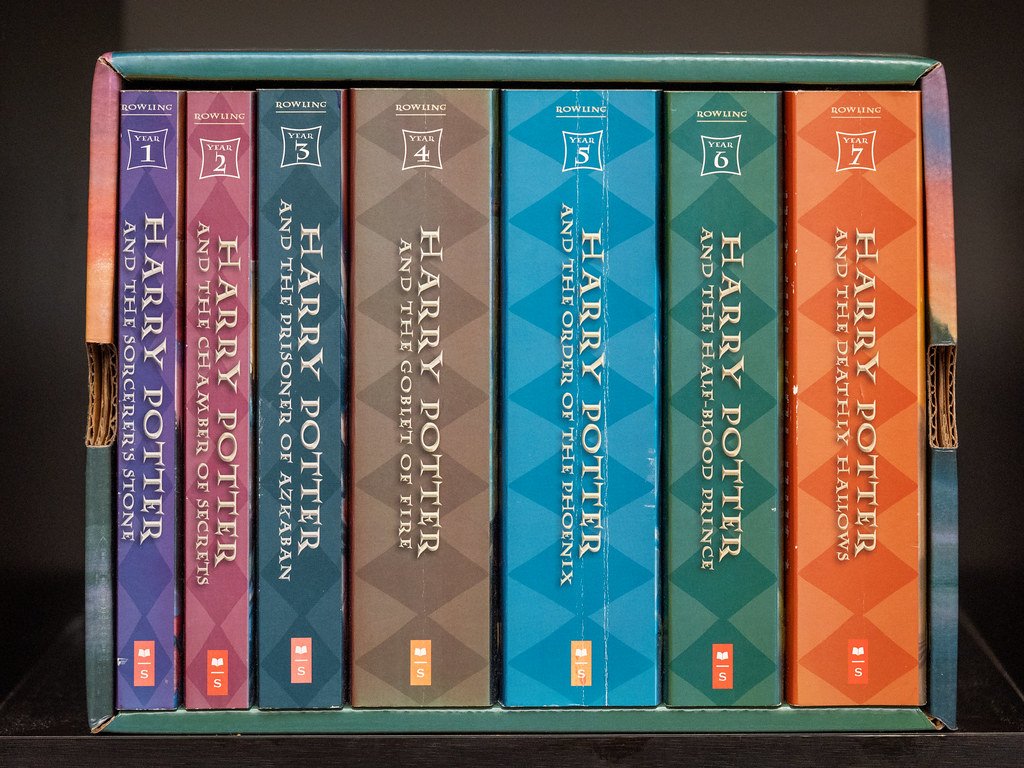

I plowed through all the novels in a matter of a few weeks. Like the first book, the second and third, Chamber of Secrets and Prisoner of Azkaban, are relatively short, but starting with book four, The Goblet of Fire, Rowling, perhaps using her newfound publishing power to defy editors, started writing tomes of 700 and 800 pages. Again, it is a testament to the books’ quality that I tore through them with ease. They consistently held my attention.

Now sixteen years later I recently took another U.K. trip. This time, with our two older kids in tow, we made a pilgrimage to the Harry Potter Experience in Watford, just north of London. Even for casual Potter fans, this is a great venue. The site is the studio where the Potter films were shot. It contains many of the original sets, costumes, animatronics, etc. that made up the films. Gringotts Bank and Diagon Alley are almost worth the price of admission themselves. You can even drink some real-life butterbeer.

This visit inspired me to re-read the Potter books. As of this writing I am at book six, The Half-Blood Prince (that dastardly Draco Malfoy has just petrified Harry on the Hogwarts Express). It’s my third time through the books. I reflect upon how my perspective has changed after a span of sixteen years and now with four children of my own.

Potter and his creator, J.K. Rowling, have been in the news lately, mostly due Rowling’s defense of gender essentialism and concomitant opposition to radical gender theory. The podcast “The Witch Trials of J.K. Rowling” was highly popular (and discussed in these pages here). Recently Rachel Lu penned a perceptive piece on the latent gender conservatism that underlies the Potter books.

The “Witch Trials” podcast naturally considers the early opposition to Potter in some Christian quarters due to its positive portrayal of witchcraft. Many years ago, I found this essay (written after the publication of Prisoner of Azkaban and as the films were just being released) quite helpful. It is an informed, critical take on Potter and magic, ultimately giving the books a qualified endorsement. I agree with this assessment. The positive depiction of magic by Rowling, as the essay details, differs importantly from the two great twentieth-century masters of fantasy, JRR Tolkien and C.S. Lewis.

In Tolkien and Lewis, shaped as they were by orthodox Christianity, magic is depicted as corrupting and dangerous, reserved only for particular characters, never allowed for humans (remember, Gandalf only appears human). Rowling is less discriminate. To that extent, Rowling’s embrace of magic is troublesome, but even that is with qualification. The books show how magic can seduce people to evil and present a temptation to great cruelty. The depiction of magic is ultimately equivocal. Certainly, the main virtues of the central characters, Harry, Hermione, and Ron, are their courage and faithfulness, not their felicity with a wand.

More worrying is the constant rule breaking and lying by Harry and the gang. Rachel Lu notes this as well. Rowling has a tendency to paint figures in black and white. Because Harry and his pals are “the good guys” and their opponents are often cartoonishly bad, the stories tend to justify misbehavior if done for a good cause in opposition the “right” people. We all know what the road to hell is paved with. Still, there are various instances where Harry’s impetuousness, tendency toward deception, and occasional self-righteousness has disastrous consequences, none more dire than the conclusion of The Order of the Phoenix.

One also comes to notice the shortcomings of Rowling’s storytelling. I have read Lord of the Rings nearly twenty times. It has never gotten old or seemed tedious. Rowling, on the other hand, with plot-driven stories that often resort to obvious tropes, just doesn’t hold one’s attention as much once you know what is going to happen. As stated, Rowling often resorts to caricatures, especially in her evil characters. There is the recurring problem of how a group of bumbling kids regularly figure out puzzles that elude what are supposed to be the wisest wizards in the world. Gringotts Bank is impregnable, for example, until the plot demands that Harry, Ron, and Hermione need to break in.

It is apparent that Rowling simply made up much of her wizarding world as she went, violating one of Tolkien’s commandments–namely that an imagined world should be well thought out and internally consistent. Rowling regularly introduces new important wizarding phenomena right when they are most convenient for the plot (e.g., werewolves in Prisoner of Azakaban, portkeys in Goblet of Fire, the Thestral creatures in Order of the Phoenix, inferi and horcruxes in Half-Blood Prince, even the whole concept of the Deathly Hallows, especially the Elder Wand, in the final book). Finally, in a mark of subpar mystery writing, secrets are kept from the reader, usually under the guise of “protecting Harry” or “they’re too young to know,” only to be revealed at the plot’s convenience.

Still, the Potter books constitute gripping and effective morality tales. I have focused on the shortcomings of Rowling’s writing. Yes, she’s nowhere near Tolkien in talent, or even Lewis, who, like Rowling, was more clearly writing for a youthful audience. But the stories are page turners that maintain a level of excitement even upon multiple reads. You wouldn’t confuse the Potter books with great literature, but for popular writing they are very well done. Also, despite my criticisms, Rowling’s wizarding world truly bears the mark of high imagination. It’s a compelling vision that one enjoys returning to on occasion.

And while the books are morally problematic (with the lying, rule breaking, the temptation toward superstition), there is enough virtue depicted to outweigh the less virtuous aspects. One cannot deny that Rowling vividly and compellingly depicts courage, honor, faithfulness, forgiveness, and sacrifice. The books treat positively all these virtues while the evil doers in the books are obsessed with power, money, status, and, most importantly, are willing to do anything to avoid death.

There is a Christian undercurrent to the Potter stories, not explicitly stated but just below the surface. Indeed, in the end Harry is a Christlike figure, albeit a significantly flawed one. In the final book, Harry finds written on the gravestone of the sister of Harry’s great teacher, Albus Dumbledore, this quote from Matthew 16:21: “Where your treasure is there your heart will be also.” One cannot miss the series’ central message, that of self-sacrifice in the name of a higher love that we will fully encounter after death.

So, I would recommend Harry Potter to readers young and old, although the young should not read unsupervised. The books are fun. They are ultimately edifying. At the end you can say proudly, “Well done, Harry.”