An anxious, heartbreaking decade looks better at the movies

Why did Marty McFly want to go back to 1985, anyway?

I mean beside the fact that he was disappearing from time.

Marty ends up in a 1955 that is, by all available evidence, significantly better than his 1980s starting point. The 1950s are clean, patriotic, and fully-employed. You can smell the hope and promise coming off Hill Valley, California like a new Oldsmobile.

(Note to young people: This essay is about the 1985 film Back to the Future, a Hollywood blockbuster that shaped many Millennials and Gen Xers. It’s about a kid who travels back in time and—get this—accidentally stops his mom and dad from meeting! So he has to get them back together or he won’t exist anymore. It’s a little problematic, but it’s probably better than that new Transformers movie. John Mulaney has a bit about it.)

(Also, the time machine is in a DeLorean, so you can see what everyone in 1985 thought cars would look like in 1997.)

Steven Spielberg’s movie is worth a re-watch these days. The film begins with Marty’s zany skateboard ride across the town of Hill Valley—where viewers see decrepit old buildings, boarded-up shops, omnipresent litter. The old diner has been converted into an aerobics studio. The local movie theater shows triple-X films.

When Marty gets thrown into 1955 all that changes: Downtown Hill Valley is new and vibrant. The cars are sleek, shiny, and new. Motorists pull up to a gas station and several attendants emerge, ready to work. The theater is clean right down to the gums, with a Ronald Reagan western on the marquee. Who wouldn’t want to stay?

It’s nostalgia, of course; Spielberg and the filmmakers were recreating the fifties as they remembered it from their own childhoods. The modern equivalent might be the Duffer Brothers’ take on the 1980s in Stranger Things.

(Note to old people: Stranger Things is a horror-adventure series streaming on Netflix. It has its ups and downs, but it’s better than whatever you’re watching on CNN.)

But fifties nostalgia is different from eighties nostalgia because no one claims the eighties were a Golden Age, while plenty of Americans look to the 1950s as the bellwether of how things ought to be. In a 2020 poll over half of Republicans thought that things in America were better in the fifties. The Good War was over and Manifest Destiny was back on track.

It is not just political nostalgia that’s at work here: In April, Paramount+ launched The Rise of the Pink Ladies, a musical sequel to Grease—a 2023 exercise in nostalgia for a 1972 exercise in nostalgia for 1959. In a commercial tie-in, the fast-food chain Sonic announced it would now serve a “pink lady” drink for anyone who wanted to “get transported to the land of doo wops and pink poodle skirts.” The implication, of course, is that everyone is going to want to do that. As with Hill Valley: Who wouldn’t want to go?

This vision of a tidy, productive 1950s is fictional. It is more Leave it to Beaver and Seven Brides for Seven Brothers than the murder of Emmett Till or thalidomide babies or twenty-three nuclear weapons detonated at Bikini Atoll.

The actual 1950s was a decade on the brink of nuclear destruction, shot through with American anxiety and violence. Both the Soviets and the Americans had The Bomb: International politics took on a horrifying existential edge. A mistake meant the destruction of all life on earth, and that hung over every minute of every day of the 1950s. Beyond that, the United States committed itself to fighting communist aggression worldwide—a worthy goal, but one with consequences unapparent in Back to the Future. Fighting North Korea’s invasion of South Korea cost tens of thousands of American lives and involved a conflict with Communist China. American decisions to overthrow democratically elected regimes in Iran (1953) and Guatemala (1954), and to tacitly support suppression of democracy in Cuba (1952) and elsewhere, resulted in thousands more deaths and the rise of brutally repressive regimes in all three countries.

American law in the 1950s did not recognize gender as a protected status; women could be fired simply for being women.

It was the fifties, not the sixties, that gave rise to the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the integration of Little Rock High School, sit-ins at lunch counters—and the extraordinary violence that met every single Civil Rights protest. Arkansas Governor Orval Faubus ordered state troopers to prevent integration. Organized mobs later attacked the school and threatened its black students. Faubus called the crisis a “usurpation of power” by the federal government. And Faubus was merely the most infamous of a cadre of governors who threatened to violate the Constitution and commit violence rather than have Black children educated alongside their white peers.

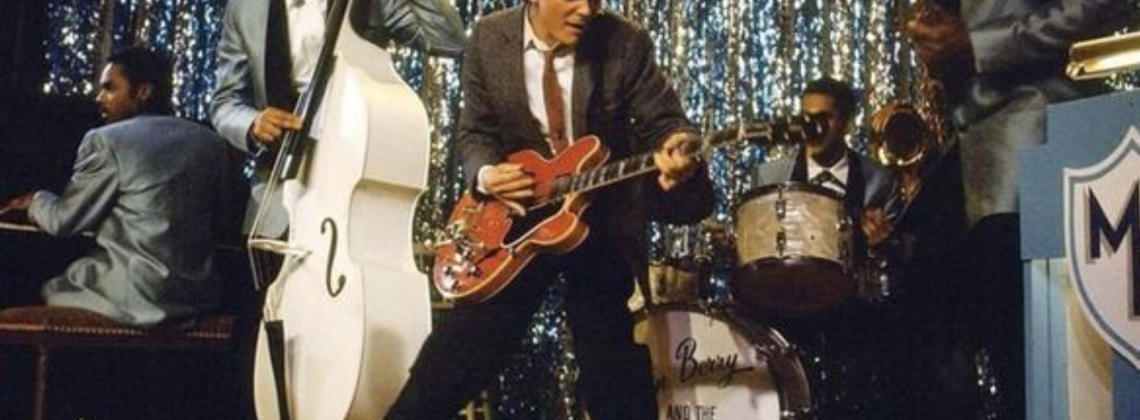

Marty McFly sees none of this in 1955. Hill Valley is virtually all white. (Yes, I know in 1985 Hill Valley has elected Mayor Goldie Wilson, who as far as I can tell is one of five Black people in the entire town. The other four are in a doo-wop band.) The only reference to politics comes when Doc Brown asks Marty who’s president in 1985. Marty’s confident answer: “Ronald Reagan.” Brown’s response: “The actor?” (When I taught this movie in history class, I had to explain how this joke brought down the house when I was kid.)

The economy of the fifties was great, though: GNP in 1959 was five times what it was in 1946. Of course, the world’s other major economies—Britain, Germany, Japan, China, USSR—had all been wiped out by World War II. Nor did good times staunch American pain; America suffered from massive and largely unacknowledged addiction to nicotine and alcohol. (As David Farber writes, many young people in the 1950s “had seen their elders blasted more than a few times.”)

TV and movies from the 1950s showed little of this pain and struggle. Hollywood still operated under the Production Code, which banned the depiction of subjects considered immoral—including nudity, surgery, homosexuality, and interracial romance. It banned the depiction of “white slavery” but not of slavery in general. Films had to present the law positively and never for comic effect, lest the media “lower the moral standards of those who see it.”

That meant that most of 1950s TV and movies never got around to addressing legal segregation or legal inequality for women or the arms race. When Rod Serling tried to write a TV movie about the Emmett Till lynching the studios refused to carry it. Serling eventually covered up his social commentary by making it about space aliens; his work became The Twilight Zone, probably the closest thing 1950s TV had to matching the American reality.

The point is historical, rather than political: The 1950s was a rough, violent decade. We idealize it at our peril, harming ourselves by turning the Eisenhower years into a Golden Age. It can make us forget that our own fears—about war, national security, violence, the rule of law—have precedents in the past. America in 2023 has not somehow “lost” the fifties. Hill Valley is a mirage.

Enjoy your fifties nostalgia. But don’t mistake it for the real fifties. Even Marty McFly wanted to get out of there.

Adam Jortner is the Goodwin-Philpott Professor of History at Auburn University. He is the author of The Gods of Prophetstown and the Audible original series American Monsters.

Image: Universal Pictures