Baseball cards reveal a timely truth: innocence endures

I’m an adult and I collect baseball cards. That sounds like a Twelve-Steppy confession. So, note to self: Seek help.

Not long ago I was browsing at the baseball card shop. A guy came in and, by the flustered music of the door chime and the way he beelined for the shop owner, I knew something ugly—though common these days—was about to happen. All I could do was brace myself.

“I’ve got a ton of baseball cards from when I was a kid,” the guy said, “And I want to sell them now.”

There was, then, a hush in which I’m sure I could hear the shop owner’s eyes roll in his skull. But dutifully he said, “What have you got?”

“I’ve got . . .” And the guy began to rattle off a murderers’ row of greats with Hall of Fame careers who played the game just before the turn of the century—ahem, the turn of the twentieth century to the twenty-first. Wade Boggs, Ken Griffey Jr., Chipper Jones, Kirby Puckett, Frank Thomas—

The shop owner cut him off. “Take them out to your backyard and use them for kindling. They’re more valuable that way.”

Merciless? Yep. But also: The Truth. It’s anybody’s guess, and guess high if you’re putting money on it, how many times that shop owner has said the same thing to other kid collectors, now adults, who figured it was time their old collections finally paid off.

My heart breaks for that guy, though. I mean, I get it. Flashback to an Eden-esque summer afternoon. There I sit with a couple young buddies on my parents’ front porch. We’re trading baseball cards. To us, in the moment, there is nothing else. But then a slithering thing from the jungle of adulthood appears in our midst. It says, in a raspy, reptilian voice, “Baseball cards, huh? One day, they’ll be so valuable you’ll be able to put your own kids through college.”

In that instant we realized we had a Future and that it was trying to crush us. Card collecting changed from stiff sticks of bubble gum and ball player heroes into the only solution for a massive, inevitable quandary waaaaaay down the line. We had to plan accordingly, and our plan was ramshackle, impotent, and, in hindsight, bitterly ironic. Not even a plan really, just something we said we’d do because we felt like we had to.

“We’ll hoard our cards,” we promised, “For the love of our children.”

We were, of course, children ourselves. Whose own children, to whom we’d suddenly become hopelessly indebted, were decades away from their own births. But baseball cards were the only transferrable commodities we had, the only tangible that would count for anything when we passed into adulthood. In our blindness we hoped that would be enough, and hope was the one thing—we hoped—that had the power to hold all things together.

Baseball cards, but also, for me, football, hockey, and basketball cards, though baseball cards made up the bulk of my collection then, as they do now. Somewhere around my own departure for college, long after my pals and I had exchanged card collecting for pursuits more suitable to our age (e.g., hanging out in coffee shops sipping cappuccinos and listening to local troubadours strum “Here Comes the Sun”) I begged my parents, “Please. Don’t ever throw away my cards.” They never did.

But I, and my pals, amassed our collections in the late eighties and early nineties in what is now, in the world of card collecting, called the Junk Wax Era. “Wax,” because baseball cards traditionally came in wax paper packs whose folds true collectors can hear, even now, crinkling and popping apart as they open them on the planes of memory. Ironically, the Junk Wax Era saw the end of actual wax paper packs, as the companies that produced baseball cards traded up for slicker packaging and bigger market shares.

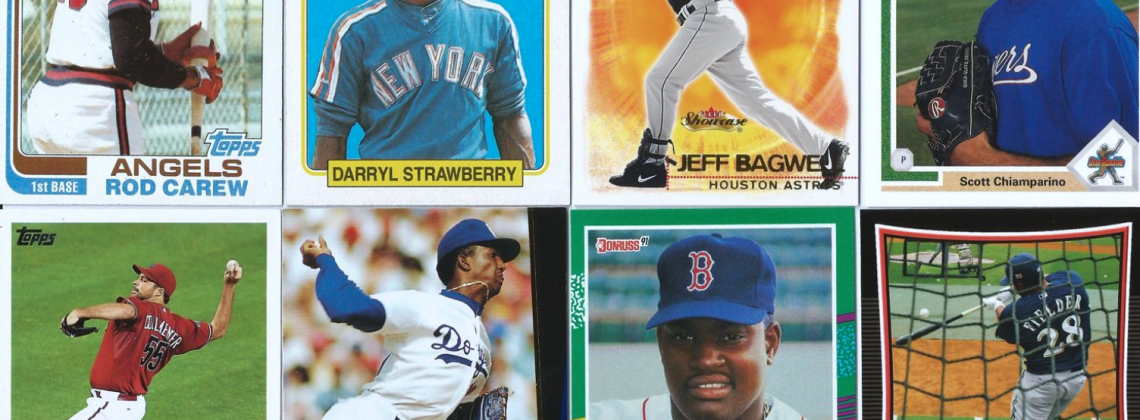

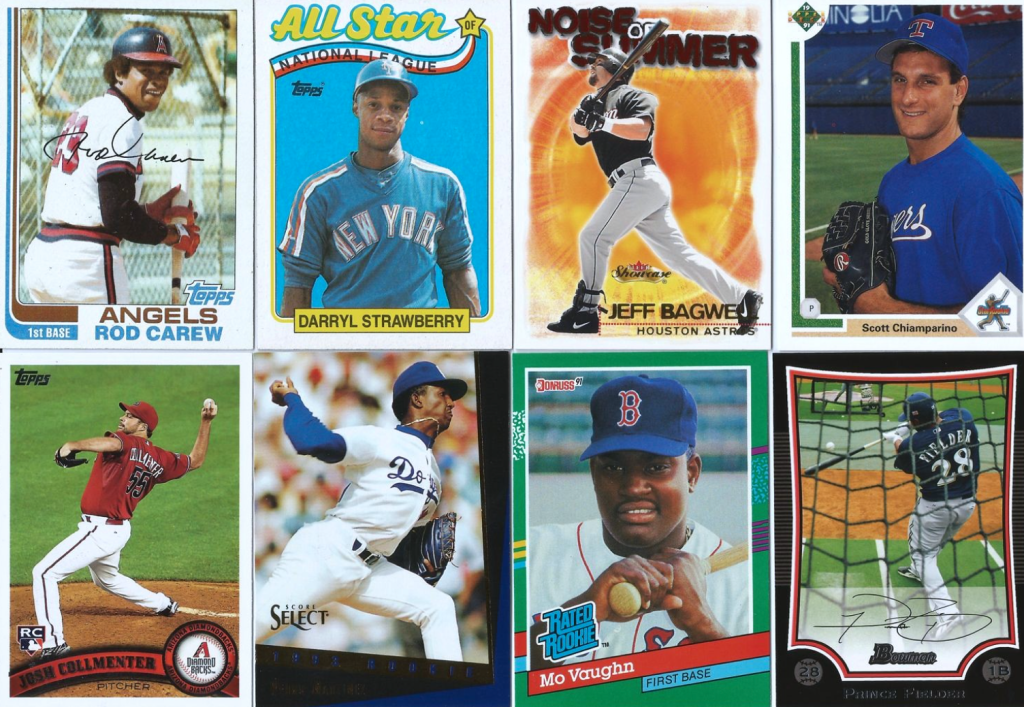

And “junk” because . . . well, in the Junk Wax Era, the card collecting business, especially baseball cards, mushroomed. New brands materialized out of nowhere in the stalwarts’ shadows—Bowman, Donruss, Fleer, Leaf, O-Pee-Chee, Pacific, Pro Line, Pro Set, Score, Topps, Upper Deck, ad nauseum. And, in addition to annually produced, stuffed-to-the-gills sets of standard cards, nearly every brand also offered a line of premiere cards. Glossier, slightly sturdier, and more expensive. Like what Lexus is to Toyota, Ultra was to Fleer, Platinum to Pro Set, Stadium Club to Topps. Baseball cards, it’s worth mentioning, were originally little promotional tchotchkes designed to help sell cigarettes, and, after that, bubble gum. Topps, probably the most well-known baseball card brand to this day, was in the gum business before there even was a baseball card business. Mid-twentieth-century, pre-Junk Wax Era Topps cards are branded on their backs, in tiny type: T.C.G. . . . Topps Chewing Gum.

Competition hit screamingly absurd levels and brands tried everything to differentiate themselves from their rivals. Each brand featured players on standard cards but also on Rated Rookies, All-Stars, Record Breakers. Over in football, cards featured players in their street clothes, relaxing at home with their families. There was even a subset that depicted players’ wives. I recall, in basketball cards, one that featured DJ Jazzy Jeff and the Fresh Prince. The market flooded and the entire industry tanked. It was card collecting’s version of Wall Street, circa 1929.

But resurrection, of a sort, came to the hobby in an unforeseen way. In the spring of 2020, COVID-19 forced us all to stay home and, quickly, we got bored. So, we started digging through all our old stuff. In attics and basements across the land grownups beheld the actual baseball cards they’d gathered as kids, sometimes for the first time since they had actually gathered them. Nostalgia, certainly, but something more.

I discovered, simply, that I still love baseball cards. I admit I check Beckett now and then, but it’s not about their monetary value. I love what they represent, something difficult to put into words, but something durable and good—a je ne sais quoi encapsulated elsewhere in Terrence Mann’s line from the end of Field of Dreams:

America has rolled by like an army of steamrollers. It’s been erased like a blackboard, rebuilt, and erased again. But baseball has marked the time. This field, this game—it’s part of our past, Ray. It reminds us of all that once was good. And it could be again. Oh, people will come, Ray. People will most definitely come.

All that once was good about the country, yes, but all that once was good about me. The cards represent a game that somehow symbolizes an unsullied version of myself that I’ll never fully realize, but to which I will always aspire. Pure, simple, heroic. I thought all that had disappeared from my concept of self a long time ago. But it hasn’t gone anywhere at all and, what’s more, it’s gotten supremely tired of being ignored. There is such a thing as an enduring innocence that transcends our basest motivations. A kind of ruggedness of heart that can go on and on. I think I took up the hobby again to tell myself about the person I want to be.

Paul Luikart is the author of the short story collections Animal Heart (Hyperborea Publishing, 2016), Brief Instructions (Ghostbird Press, 2017), Metropolia (Ghostbird Press, 2021) and The Museum of Heartache (Pski’s Porch Publishing, 2021.) He serves as an adjunct professor of fiction writing at Covenant College in Lookout Mountain, Georgia and lives in Chattanooga, Tennessee.

On the heels of watching LSU beat Wake Forest in dramatic fashion, baseball is on the minds of all Louisianans this weekend.

And when I think about baseball, it’s hard not to transport myself back to the exact era you recall here: the late 80s to early 90s heyday of baseball cards. In fact just last week, I was trying to explain to my mother in law why cards had lost their charm– and their value– and your assessment was the same as mine: the explosion of special lines and new fancy brands capitalizing on the fanaticism of collectors of the day actually smothered the fire they hoped to fan. As you say, it was a future that my friends and I could not have imagined. But the simplicity and the wonder and the feeling of kinship with the earlier eras of cigarette cards from the 1910s and the Topps cards of baseballs golden mid century era- all that was somehow lost in the glitz and glitter of the upper deck. Even my friend Abel, who had inherited all sorts of wildly valuable cards, including a Ty Cobb cigarette card (or two), a Willie Mays rookie error card (Mays spelled ‘May’), most likely had to find alternative means of funding his kids education (why was it always college that we were planning to pay for, I wonder?).

By the way, what will you give me for a donruss ’86 set, unopened in the box? The Canseco rookie card is in there waiting for you!! I’ve got a 14 year old and need to start cashing in his college fund… or maybe he should save these cards for his son or grandsons. By then they’ll surely be worth millions.