Now that the country has once again survived a trip to the brink of financial chaos in exchange for concessions related to the debt ceiling, it’s worth asking why the United States has such a large federal debt and what (if anything) can be done to bring it under control.

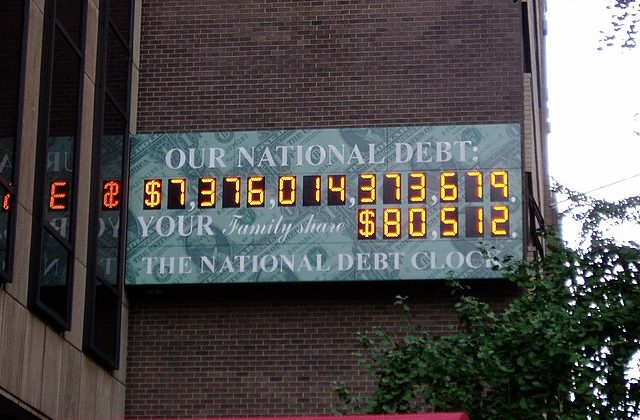

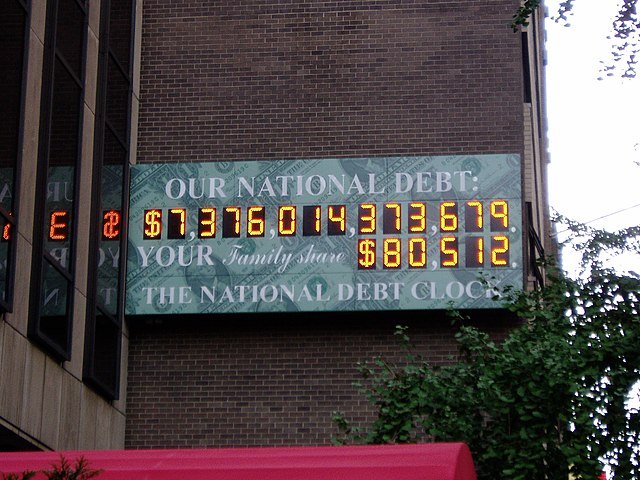

The US government currently owes its creditors more than $30 trillion, which is more than the country’s annual GDP. At this point, if all of the goods and services produced in the United States for the next year were used to pay down the government’s debt, the US would still owe several trillion dollars at the end.

But while numerous people want the government to reduce its debt, few people understand how it can be done, because they don’t know the history of how the US acquired its debt. Many people imagine that the debt comes primarily from government waste or from unnecessary, expensive social programs. But the truth of the matter is that for most of US history, the debt has come mainly from military spending, combined with inadequate tax revenues.

Before the twentieth century, the US military was quite small, so for the first 175 years of the country’s existence, nearly all of the federal government’s major deficit spending came during wartime, when the country had to spend massive amounts of money on short notice.

This phenomenon started during the American Revolution, even before a national government was fully formed. The US government was born in debt, because during the Revolutionary War, the Continental Congress financed the war through borrowed money and the promise of later payments. After the war, the federal government, at the urging of Alexander Hamilton, agreed to assume the debts of the states as a way to create national unity around a federal system. President George Washington warned the country about the problem of large debts, but after he died, the War of 1812 resulted in additional borrowing.

While several presidents temporarily eliminated budget deficits and helped to reduce the size of the debt, their peacetime savings were rarely enough to offset the debt accrued during wartime borrowing. In fact, there has been only one American president who has ever paid off the entire debt. That president was Andrew Jackson, who paid off the federal debt in 1835 – the first and only time in US history that that has ever been done. He did so by selling large amounts of Western land and drastically cutting spending on road and canal construction.

But the financial panic of 1837 made it impossible for Jackson’s successor, Martin Van Buren, to continue running budget surpluses. The Mexican War also added to the debt.

By far the greatest source of government debt in the nineteenth century was the Civil War. Between 1861 and 1865, the US federal debt increased by 4,500 percent (from $60 million to $2.7 billion). The US government was never able to fully pay off its debt after that point, despite years of budget surpluses during the Gilded Age. In an era when the country lacked an income tax (or had only a very modest one), it took decades of slow revenue growth to pay off the debt from a single war – and in the case of the Civil War, the country wasn’t able to do it at all.

World War I and, to an even greater extent, World War II likewise increased the government debt. Fiscal conservatives worried about the government’s increased deficit spending during the New Deal of the 1930s, but that was a drop in the bucket compared to the amount the government borrowed to finance World War II. The federal debt increased by more than 500 percent between 1941 and 1945.

Shortly after World War II, the US embarked on a prolonged period of permanent military buildup as part of the Cold War – which meant that the US government’s level of spending would have to remain on a permanent wartime footing. Never before in its history had the US done this.

The only way that it could finance this without a massive increase in the deficit was by keeping income taxes at extraordinarily high levels. From the 1940s through the early 1960s, the federal income tax rate for the top marginal tax bracket for the highest income earners remained set at 91 percent, and even after the Kennedy administration cut taxes, this rate was still set at 70 percent from the early 1960s until the 1980s.

The government’s high level of Cold War spending fueled job growth and productivity. Unemployment levels remained below 5 percent most of the time in the 1950s and 1960s, and wage growth and increases in the GDP reached some of their highest levels.

Even with the high level of taxation on the highest income earners, the US was not quite able to entirely avoid budget deficits, but the high rates of economic growth, combined with high levels of taxation, kept deficits modest and prevented the federal debt from ballooning out of control.

Between 1950 and 1970, the federal debt did not even double, even as the country fought two wars (Korea and Vietnam), built thousands of nuclear weapons, constructed a multi-billion-dollar interstate highway system, created Medicare and Medicaid, began giving federal educational aid to students for the first time, launched the food stamp program, and sent people to the moon.

The nation’s faltering economy in the midst of the energy crisis of the 1970s created inflationary pressures that increased the federal debt, but it was not until President Ronald Reagan’s tax cuts of the 1980s that the country started to see exponential increases in the budget debt. When Reagan took office, the federal debt was still less than $1 trillion. By the time he left office, it was $2.9 trillion – a nearly three-fold increase.

The reason for this increase was that Reagan was committed to high levels of Cold War military spending but not to the tax rates that would have been necessary to pay for them. Even as his defense budgets doubled over the course of his first five years in office, he reduced the top marginal tax rate from 70 percent to only 28 percent.

President Bill Clinton reduced military spending and raised taxes on the wealthiest Americans – which, in a decade of high economic growth, was enough for him in 1997 to propose the first balanced budget that the federal government had had since 1969 and to keep it balanced during his final four years in office. Most of the federal debt still remained, of course, but at least the country experienced four years of no deficit spending.

As soon as President George W. Bush came into office, he passed new tax cuts and then engaged in a new military buildup following the terrorist attacks of 9/11. The effect on the federal debt was predictable: It nearly doubled during Bush’s time in office.

Since that time, the US has continued to experience several major financial crises, including the Great Recession of 2008 and the COVID-19 shutdown in 2020, both of which resulted in increased federal spending and decreased tax revenues. The US government has spent trillions in economic bailouts.

But it has also continued to spend large amounts on the military; the $800 billion that the US spent on the military in 2021 was nearly twice as much as the $450 billion that the US spent in 2002, when the country was fighting a war in Afghanistan and preparing for an invasion of Iraq.

And the US has mostly resisted new tax increases, largely because the Republican Party is adamantly opposed to any new taxes and the majority of Democrats are interested in tax increases only if they are confined to the richest 1 percent and are relatively modest in scope.

Despite their rhetoric to the contrary, both parties are essentially committed to maintaining the Cold War state’s high level of government spending, but neither party wants to raise taxes to the level necessary to pay for it.

If we’re concerned about the federal debt, we need to recognize that negotiations over the debt ceiling will not be enough to solve the problem. Either the US can commit to substantially higher taxes or it can settle for a radically smaller government, with a military that is only a fraction of its current size. As long as Americans are not willing to make the sacrifices required for either of these options, we can’t expect the United States to make any real reductions in the size of our national debt.

Thanks for putting the current budget debates in a much needed historical perspective, particularly with respect to taxes. The 1950s seems, ironically, to have been the golden age of socialism in America, at least in terms of income tax rates. I’m ok with that. This historical example, and the current example of other Western states (e.g., Germany), show that higher taxes and a more generous social safety net are compatible with economy growth. Still, is it fair to place so much blame on the military budget? Paul Krugman and others have quipped that the federal government is an insurance company with an army. Though perhaps stingey by European standards, the biggest chunk of the federal budget, almost half (by one set of numbers I came across) goes to SS, Medicare and Medicaid, with only about 12% going to the military. Yes, the U.S. spends far more on the military than any of its allies, but largely because it has assumed the responsibility for policing the world. Would European social democracies be so generous if they had to defend themselves and provide international policing to ensure the free flow of goods in our global economy? I would be happy to see the U.S. military return to its pre-WWII/Cold War size, and happy to see tax rates return to something like the 1950s. Neither party seems interested in either of these policy goals. I suppose, as someone who grew up in a New Deal Irish Catholic household, I am more concerned with the state of the Democratic Party. You rightly indicate that for all of their talk of commitment to helping the poor, Democrats have largely acquiesced in the Reagan tax revolution; I think too often the left/liberal attack on military spending is a smoke screen for that basic betrayal of the mid-century New Deal vision. Would that Democrats showed the same commitment to raising taxes on the rich that they show for defending Planned Parenthood, abortion and trans rights.

So, a question I should know the answer to: To whom do we owe the debt? Foreign entities? Future generations?