Jacob Hiserman is a doctoral candidate in History at The University of Alabama. He received a B.A. in History from Christendom College and an M.A. in History from Baylor University. Jacob lives with his wife and two boys outside of Birmingham, Alabama, where he enjoys gardening with his family. We are excited to welcome him to the Arena today to tell us about his current dissertation research.

I read many stories about nineteenth-century southern college chapel for my dissertation—some grave, many funny. Students thought quite a bit about chapel worship— the public divine-human drama of sacred actions that built relationships with God and others worshipping Him, though one wouldn’t know it from the Janus-faced historical portraits of those collegiate exercises.

Historians normally portray chapel as a harbinger of secularization or a mere chronicle of student antics. Yet, student musings on chapel drew me to tell a different story about chapel liturgies. I seek a narrative that combines faculty and student views of chapel worship. That quest led me to some guiding questions for my project: How did students and faculty think about and form—others or themselves—at chapel liturgies? Why did chapel worship last throughout the nineteenth century at southern Christian colleges? What was chapel liturgy’s role in crafting collegiate identity and southern religious culture through college graduates?

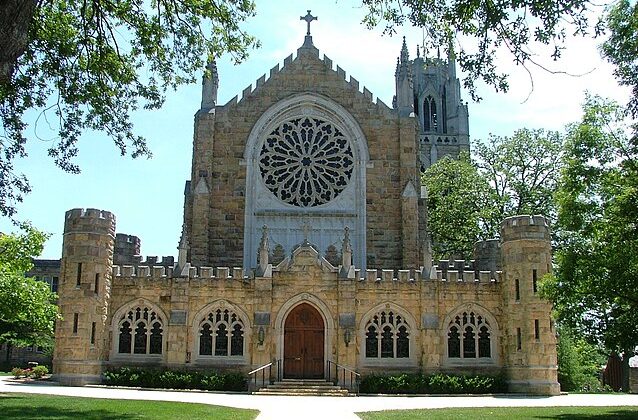

I discovered answers to those questions in conflicts over chapel worship. Soon, big intellectual themes emerged from such tussles between persons at Protestant (Davidson, Sewanee, and Baylor) and Catholic (Mount St. Mary’s) institutions. Those are propriety, discipline, order, cultural authority, and duty. Tentatively, five chapters explore each of those ideas in practice. Through them, I illustrate how various contexts—including the Lost Cause, middle-class values, European religious and philosophical influences, and manhood—stemmed from and shaped chapel liturgies. I’m wrestling with how those five notions, their cultural backdrops, and complex usages relate to moral philosophy and tradition.

Students also did some of the sparring. Antebellum Davidson students seized and rang the chapel bell, repelling faculty attempts to retake the bell with rocks and stones. Postbellum Sewanee students stole the undergrad chapel bell’s hammer and clapper while Baylor women of the same era rang their campus bell and (on a later occasion) silenced it. Medieval women also subversively rang church bells at night.

What were Catholic collegians up to as regards bells? At antebellum Mount St. Mary’s, they (and their president) likely wanted the chapel bell replaced with a drum. Rev. Simon Bruté, the Mount church’s French expatriate pastor and seminary professor, objected against such “military folly.” Perhaps he desired (where Protestant and Catholic students disliked) a continuation of a medieval Catholic tradition against a bourgeois military fad.

Tradition, whether maligned or defended, continually provokes large questions that drive my thought: In what ways does historical interpretation change when humans acts are judged not only from an anthropological principle of individual autonomy, but also from a related and complementary anthropological premise of community-through-tradition? How did concepts of tradition animate the intellectual worlds and actions of people in the past? How does one hold in tension intellectual (and cultural) continuity across time with contextualization?

It seems like a tricky balance amid striking medieval parallels to nineteenth-century praxis; one continually complicated by simple student youthfulness, among other factors. Whether reckless or sober, students vigorously maneuvered their bodies and minds in relation to chapel liturgies. Faculty acts prompted but also responded to student ones. Their relationships demonstrate a leitourgia (public drama) about tradition, morality, and higher education that played a part in southern religious culture.

What a splendid idea for a dissertation!