What does it profit a theological tradition to gain Hollywood but lose its soul?

Exactly four years ago I was one of the millions who went to see the highest grossing film in history: Avengers: End Game. The first scene dramatizes the pivotal event of the previous film: the “Snap” committed by villain Thanos to make half of all humans disappear in an instant. In End Game we see one of the heroes, Hawkeye, lose his wife and children to the Snap. One moment he’s playing with his kids at a picnic, the next moment they’re gone.

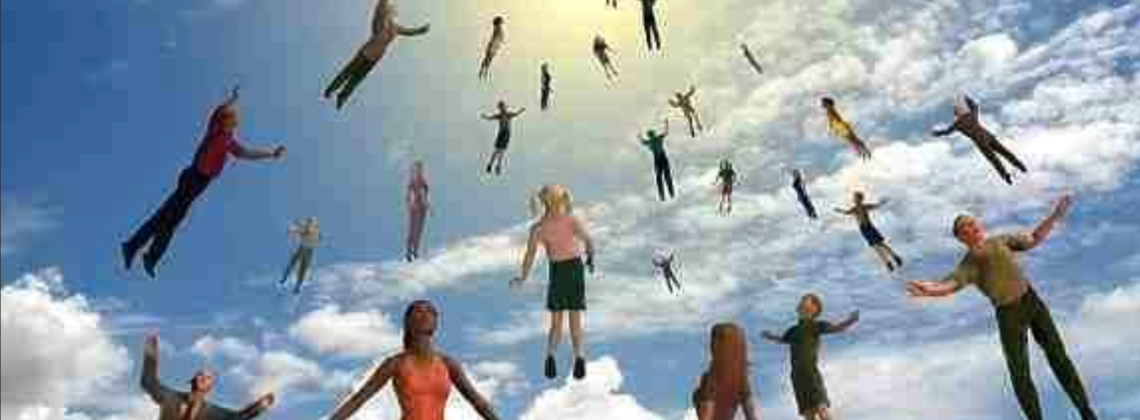

I felt an unexpected but familiar sensation when I watched the scene. It reminded me of one of my deepest religious impressions as a child who believed in the any-moment rapture, the most influential and distinctive teaching of the theological tradition known as dispensationalism, formative for many evangelicals and fundamentalists in the United States. I grew up learning that the rapture, the sudden “translation” of Christians into the presence of Jesus in heaven, could happen any given day.

It turns out I wasn’t alone. In reviews, the Snap quickly took on the nickname of the “Snapture.” It speaks to the reality of “rapture anxiety”—a shared experience by thousands who grew up in homes influenced by dispensational teaching.

Admittedly, I was more attuned than the average moviegoer. The year before I had started writing a book titled The Rise and Fall of Dispensationalism: How the Evangelical Battle Over the End Times Shaped a Nation and so, as the saying goes, I was primed like the proverbial hammer to see everything as a nail.

Counterintuitively, though, I came to see End Game’s rapture motif not as a sign of dispensationalism’s rise but of its fall. This requires an explanation. On its face, the once obscure theological doctrine appearing as a trope in one of the most popular pieces of pop culture ever is a sure sign of success. And it would be—if the point of dispensationalism had been to become a Hollywood trope in the first place. But that was expressly not the original vision, and achieving worldwide trope status, to borrow a phrase, cost dispensationalism its theological soul.

What I came to understand—and it’s this story I tell in my book—is how what we today call dispensationalism developed in three distinct stages that conclude with its appropriation and dissemination into the mainstream of American popular culture.

In the first phase, spanning roughly 1830-1900, the theology and religious culture that become the beating heart of dispensationalism took shape. The story begins with a charismatic figure named John Nelson Darby, an Anglo-Irish ex-Anglican priest who founded the Brethren sect in the 1830s. Darby’s unique ideas about interpreting the Bible, prophecy, the role of the Jewish people in history, and yes, the rapture, migrated to the United States during the era of the Civil War and Reconstruction, eventually taking hold in the burgeoning revival/publishing/Bible institute/global mission network of Dwight Moody.

The second phase, spanning roughly 1900-1960, solidified dispensationalism as a system of theology at the heart of major spheres of American fundamentalism. Tellingly, the term “dispensationalism” was coined in 1927 by a fundamentalist critic named Philip Mauro, who described it as a “modern” heresy within fundamentalism itself. But in the face of skeptics, dispensationalists rationalized, systematized, and defended their theology. They built their own seminaries—Dallas Theological Seminary being the most important—along with a massive body of scholarly publications, journals, and conferences. Thousands of pastors and others in ministry were trained in dispensational theology by the mid-twentieth century, and much of its intellectual energy was geared toward legitimizing its insights within the world of fundamentalism.

Here’s where the “fall” begins: the third phase. The scholarly project of systematizing and defending dispensationalism stalled out in the 1960s, and it’s been in decline ever since. Today there are few seminaries outside of independent fundamentalist outposts that teach dispensationalism. The old network of Bible institutes and mission agencies has largely abandoned the theology. A revisionist version, called progressive dispensationalism, dispenses with many of the key parts of the “classic” mid-twentieth century system and concedes a lot to rival evangelical views.

But at the same time that dispensationalism’s scholarly decline began, a popular form went viral in American religious culture. Dallas Seminary graduate Hal Lindsey’s The Late Great Planet Earth (1970), a simplified version of the dispensational end times scenario, became the best-selling nonfiction book of the 1970s. The Left Behind novels, beginning in 1995, have sold more than sixty million copies, with a third film reboot scheduled for 2023. In the growth of megachurches, parachurch ministries, televangelism, and contemporary Christian music, dispensationalism has made a lasting mark on popular religious culture.

And that mark goes even deeper. In politics, the Christian right—the organized political movement of conservative Christians—embedded dispensational concepts at the center of its motives for action. On crucial issues, including support for the State of Israel and debates over teaching evolution, dispensationalism has played a prominent role. In broader analyses of American politics, observers have speculated (often speciously, which is itself revealing) as to whether dispensational end times beliefs were behind the policies of Ronald Reagan or George W. Bush. In such moments dispensationalism had traveled far indeed—from rural Ireland where Darby first developed his thinking to the op-ed page of New York Times and the top of best sellers lists.

Yet this cultural-political success constitutes a fall for at least three reasons. First, the coherency of dispensationalism as an “ism” had been lost in the process. In most cases, dispensationalism became little more than an end times scenario, when at its most coherent it was a full system of theology. In terms of its credibility as a system of theology, it squarely lost the academic contest.

Second, the pop dispensationalism of the last fifty years has taken its cues above all from commercial and consumer demands, meaning it has mutated in ways big and small to accommodate the exigencies of the cultural and political moment. This has done it no favors in either shaping insightful theology or establishing institutions invested in perpetuating its teachings to future generations.

Third, because of its incoherency and detachment from theological inquiry, pop dispensationalism has survived by enfolding itself into political and cultural projects that have little regard for either coherency or adhesion. It’s status today is closer to a folk religion, a cache of tropes in dystopian fiction, and grist for conspiratorial thinking. The shrinking community of classic dispensationalists that seeks to integrate eschatology into a broader theological framework have little influence and little traction with younger Christians.

Falling is not the same thing as disappearing. American Christians walk among the ruins of a once imposing dispensationalist edifice that influenced a wide swath of evangelicalism, and now by its absence does so, too. Christians can’t avoid the debris—either the legacies of its theological project or the spaces its collapse has left empty. And sometimes, when the sunlight shines from a certain angle on the wreckage, observers may ponder with a sort of awe how such an edifice was ever built in the first place, and what brought it crumbling down.

Daniel G. Hummel is Director for University Engagement at Upper House (Madison, WI) and a research fellow at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His writings on religion, culture, and diplomacy can be found at www.danielghummel.com.

Very glad to have gotten your book; this information is new to me and very well organized and presented. Thank you for doing all of this.

Thanks for a fine historical perspective on the troubling history of dispensationalism.

Dan’s book is worth reading.

Would also recommend AMERICAN APOCALYPSE by Matthew Avery Sutton. Rick mcnamara

Thanks for the feedback. I’m in dialogue with Matt Sutton’s book in this one, and Matt was a valuable reader of an earlier version of the manuscript (though all devotions from American Apocalypse are my own!)

I just finished reading the book and I thank you for all the research and fine writing that went into it. I agree with your contention that the echos of dispensationalism continue to cause harm to the church and to America. In the early sixties I took a course in dispensationalism at Biola College from Nicholas Kurtaneck (Grace Theological Seminary). His course was an apologetic for dispensationalism against covenant theology. For some reason it didn’t work on me. I became convinced that dispensationalism was wrong. And yet even to this day when I cannot find someone who was just there a while ago I experience a pang that the Rapture has happened.

Thanks also for this excellent summary of the book.

Thank you, Ron. Early 60s was highpoint for the dispensational-covenant theology debates. We all enter bigger stories at unique times that shape us!