In the mid-second century BCE, Cato the Elder, Rome’s most conservative politician of his day, published his Origines, the first Roman history in Latin. Only fragments of the work survive, but we know that Cato’s history featured an unusual approach to historical writing: he wrote a history with no names. Referring to individuals only by their titles, Cato completely anonymized Roman history.

With all due respect to Cato, whose medicinal cabbage recipes remain legendary (if anything hurts, internally or externally, eat some cabbage or apply some boiled cabbage! Big if true!), subsequent historians and readers since antiquity have disagreed with his approach to historical writing. And the genre that most exemplifies the near-universal preference for history as the study of real people with known names is biography. But not all biographies are created equal. Historian Chris Gehrz, who wrote a spiritual biography of the controversial pilot Charles Lindbergh, has noted in particular the distinction between biographies that are meant to inspire and biographies that intend, rather, to do the opposite.

If we want historical accuracy, we seek biographies that tell fascinating stories about the lives of real people in all their complexity without intending to inspire either admiration or disgust in the reader. Furthermore, I contend, the best biographies are also the best microhistories—meaning, through the life of the person on whom they focus, they tell the history of a time and place in a way that is more alive and engaging than a more generic historical overview of that time and place could do.

Indeed, one of my favorite examples of a biography that does this really well is Jon Sensbach’s masterful Rebecca’s Revival: Creating Black Christianity in the Atlantic World. It is a story of a woman about whom we know very little, but just enough to reconstruct a story of her life and place her within a specific historical context. That context, in many ways, takes the front stage in the book, but Rebecca’s life story—tragic in so many ways, inspiring in others, and really just deeply complicated by the lack of sources from her own perspective—enriches the overall narrative of a time and place.

It is this same balance of telling lives of individuals, and using their stories to bring to life their time and place, that the new series of ancient biographies, Ancient Lives, from Yale University Press does so well. Edited by James Romm (whose own delightful essay on reviewing books you absolutely should read if you missed it earlier this month) the series has ambitious aims, as its summary indicates:

“The Ancient Lives series unfolds the stories of thinkers, writers, kings, queens, conquerors, and politicians from all parts of the ancient world. Readers will come to know these figures in fully human dimensions, complete with foibles and flaws, and will see that the issues they faced—political conflicts, constraints based in gender or race, tensions between the private and public self—have changed very little over the course of millennia.”

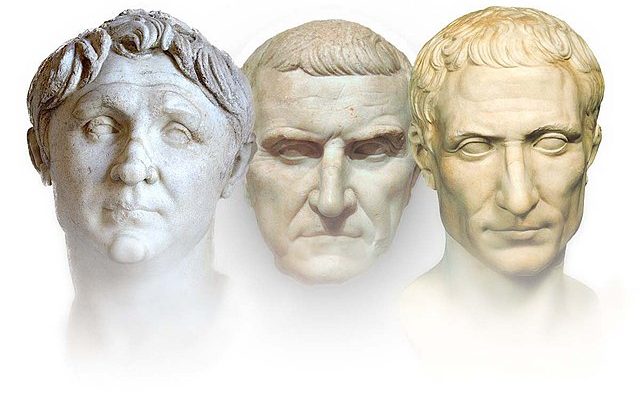

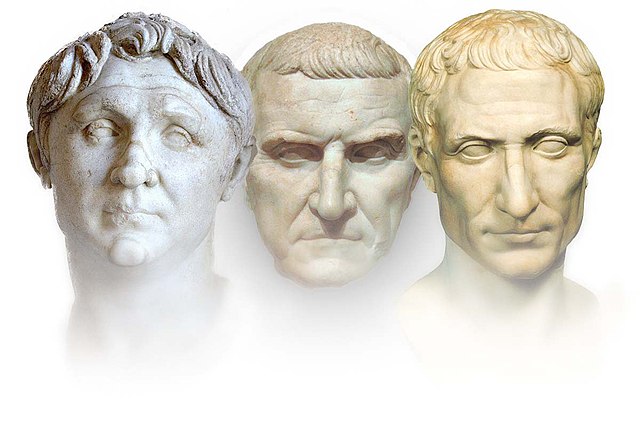

The selection of individuals on whom the four books in the series so far focus is thoughtfully quirky. They are all well-known and reasonably well documented individuals—else there would have been no way to produce a biography on them—yet they are also not, for the most part, individuals whose stories are known among mainstream non-specialist readers, who are the target audiences here. Romm’s own contribution to the series, Demetrius: Sacker of Cities, is a biography of an important Hellenistic general and politician. Peter Stothard’s Crassus: The First Tycoon (stay tuned for a review at Current soon!) is a biography of the wealthiest man in the late Roman Republic, and one of Julius Caesar’s uneasy political allies. It may be excessive to call Crassus the Trump of the Roman Republic, but some resemblances are definitely there.

I appreciate also that in addition to Greece and Rome, the series so far includes two biographies from Egypt. Toby Wilkinson’s forthcoming Ramesses the Great: Egypt’s King of Kings profiles one of Egypt’s longest-ruling and most megalomaniac pharaohs. Meanwhile Francine Prose’s Cleopatra: Her Story, Her Myth is a nuanced biography of Cleopatra and her modern reception. Of these four biographies, the last one is perhaps the only “predictable” subject for a biography in the entire series so far. Indeed, on the only occasion many years ago that my department chair twisted my arm to teach a class on Women in the Ancient World (I’m a military historian! This was well outside my comfort zone!), it was filled with very giggly sorority girls who were there specifically for Cleopatra. But this book is not your typical biography of Cleopatra. I would have loved to have this resource for my class.

Overall, this series is a great reminder of why biography has been an approach to history that both writers and readers have found so engaging and useful for education, entertainment, and reflection since antiquity. Sorry, Cato, history is much more fun with the names left in.