An advertising campaign of this magnitude invites—and requires—missional scrutiny

A gift on Valentine’s Day requires discernment. If your wife is on a strict diet, giving her a box of chocolates shows a lack of appreciation of the relational context. If the relationship is strained, the chocolates might create even greater animosity, regardless of the well-meaning intentionality. Love demands relational discernment.

Relational discernment may be lacking in the national He Gets Us campaign. The reaction to the two Super Bowl ads has been predictably negative in both the mainstream media and among those the ads seek to reach. Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, which each year grades commercials in its Super Bowl Advertising Review, gave the ads a D.

Americans are not generally opposed to Jesus as depicted in these ads; rather, they are opposed to the churches that represent this Jesus. They are leaving the church in droves, and the most likely results of these ads is, I fear, further alienation. The ads speak of child-like humility and uniform love of others. Both are true of Jesus. Neither are perceived as true of the church.

This campaign is well intentioned. It is eager to refocus this alienation from the church back to the person of Jesus and his message of love. It is eager to get a positive message about Jesus back into the public conversation. It seeks to call the church back to Jesus. These are worthy goals.

Since the early 2000s, Christianity has been publicly viewed as a cultural and social negative. The estrangement between the church and the public is real, if not uniform. It is located strongly in urban centers, in spheres of cultural influence, and among the young. This is now a cultural reality with which the church must contend.

Time will tell the legacy of the He Gets Us campaign. Research on its effectiveness is ongoing. Perhaps it is too early to be critical, but a campaign of this scope and cost deserves some missional reflection.

Marshall McLuhan stated that “The medium is the message.” He proposed that the communication medium itself, not simply the messages it carries, is the source of the message. Context matters. Given that the campaign’s two ads were placed among the fifty ads presented during the Super Bowl, the message of the ads was not really about their explicit content—humility and love—but rather their implicit context. Jesus is being presented—as was the common theme of the rest of the ads—as a celebrity-oriented consumer commodity. The medium dictates the message. Writing a positive message about Jesus on the walls of a public bathroom stall is unlikely to elevate Jesus spiritually in the minds of those using the stall. If the medium is the message, the message may well be something other than the creators intended.

The longing of the spiritually open, including many within the Super Bowl audience of 113 million, is for spiritual enchantment. They long for a personal encounter with genuine other-worldly spiritual experience. Their longing is for a mystical personal engagement with transcendence. And yet, what is presented in this campaign is an immanent Jesus, a human Jesus who is just like us. The campaign highlights his humanity, not his divinity. This may be more acceptable to the religiously suspicious, but it misses the source of their deepest spiritual longings, which is for something more than what a secular experience of humanity can offer. These ads secularize the social imaginary with a human Jesus who is disenchanted of his own spiritual reality. When it comes to Jesus, a half-truth is a whole lie. He was not simply human; he was God come to earth in human form. Little of this is communicated in this campaign. Perhaps a better question is not whether Jesus gets us, but whether we get Jesus.

Every child knows that actions speak louder than words. This is even more the case when one is addressing a hostile audience. Few people believe in the strength of words today. In fact, the Super Bowl Pepsi ad with Steve Martin was built around this premise. The thirty-second ad features Martin explaining how as an actor, it is his job to make people believe what he is doing is real. At the end of this clever commercial, Martin says: “Is it great acting or is it great taste? The only one to find out is to try it yourself.” Experience triumphs over words.

Campaign critics observe that when a non-believing skeptic goes to a church, their experience is often the opposite of what the He Gets Us ads promotes. Humility and love are met with arrogance and judgment. If the church is to overcome its contemporary cultural despisers, it will not be through words but action. Not talk, but rather lived experience, is where persuasion lies.

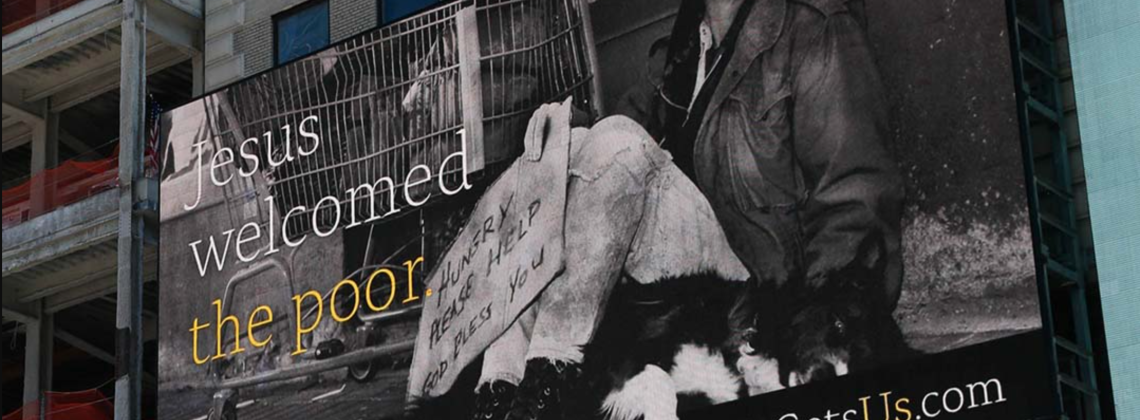

Perhaps Christians should spend their money on actions rather than words on a screen. The two television Super Bowl ads cost $17 million. The cost of the campaign over the coming years is estimated to be in the hundreds of millions. While this may seem expensive, two thirty-second engagements with Jesus comes to an investment of about fifteen cents per person. A sensible campaign critic can ask whether this a meaningful use of religious resources. Will it shift the cultural ethos regarding faith? Do not actions speak louder than words—particularly the words and images of a Super Bowl ad? It was not long ago that the same audience witnessed the on-field heart attack of Damar Hamlin. The response was reverential silence, an on-air prayer by an ESPN sports announcer, and a nationwide outpouring of support and love for him. The seriousness of the moment called everyone to prayer and spiritual dependence.

One assumes that the investment in this campaign is to change minds, to soften the hostile cultural zeitgeist against persons of faith and the Jesus who stands behind it. Its aim is also to get the church to better align with Jesus. To do so, it must change the frame from the political to the spiritual.

In the public sphere today, Christianity is viewed politically. Many have noted that the “Super Bowl Jesus” reflected in this campaign is left-leaning and progressive in his posture. Nonetheless, this is countered by the political perceptions of its campaign supporters, particularly the David Green family, worth billions—and that owns Hobby Lobby. The funders of this campaign are known to be pro-life and anti-LGBTQ+ rights. The ads do not change the political lens through which Christianity is understood in public.

Rather than change the frame, the campaign serves to reinforce a political framing. As such the frame is about winners and losers, Nietzschean power politics, partisanship, and cultural tribalism. Whoever wins the frame, wins the argument. As cognitive scientist George Lakoff has written, “When you argue against someone on the other side using their language and their frames, you are activating their frames, strengthening their frames—in those who hear you, and undermining your own views.” This campaign has not changed frames and is thereby weakening the church’s spiritual argument and blurring its spiritual identity. A post-Super Bowl review of this campaign described its supporters as “ghouls,” demonstrating the media’s negative bias. In their minds, the campaign is not about Jesus but about the continuation of the culture wars, which significantly weaken the spirituality of Jesus and his spiritual relevance to every viewer. If the frame is political, then so is its tacit message. Frames rule.

If the church is going to engage culture in a manner that furthers the advance of the gospel and the reality of the kingdom of God, it will require more relational and cultural discernment for these religious despisers. The cultural hostility toward the church is real. Much of it is due to our own actions, past and present.

The audience one seeks to address is key to determining the rhetorical strategies one implements. A box of chocolates on Valentine’s Day for a dieting wife is going to earn you no merit. If there is already hostility in the relationship, it is likely to make things worse. Persuasion demands contextual discernment. So does love.

John Seel is a cultural analyst and writer living in Philadelphia. He is the former director of cultural engagement at the John Templeton Foundation. He is the author of The New Copernicans: Millennials and the Survival of the Church and Network Power: The Science of Making a Difference.

In many ways the Asbury Revival is the counter-point to this critique. A whole hearted embrace of the transcendent Jesus by Gen Z. Go get them Gen Z. #jesusrevolution

Perhaps God called these ads into being more to remind his Church about Jesus than to convince those hostile to Christianity.