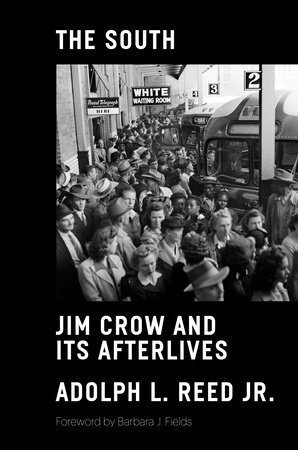

Over at Dissent, political scientist Jared Loggins reviews Adolph Reed’s The South: Jim Crow and Its Afterlives and Imani Perry’s South to America: A Journey Below the Mason-Dixon Line to Understand the Soul of a Nation. (See my review of Reed here).

Here is a taste of Loggins’s review:

Of the two books, Reed’s is the more straightforward autobiography. He is in the age cohort, “black or white, for which the Jim Crow regime was a living memory.” The book is thematically structured by his travels in the South during Jim Crow and in the wake of that order’s demise. In some ways, the book is a reflection on the rules of the racial order as Reed lived them. Under Jim Crow, blacks were subjected to the capricious will of whites. They had to adjust to certain rules and norms as a matter of life and death. At the same time, for a whole host of idiosyncratic reasons, the rules were not uniformly enforced; in fact, they were routinely violated on all sides of the color line—an indication of Reed’s view of Jim Crow’s fundamental instability. Some of the most affecting and vivid passages of The South recount how confusing it was to navigate this terrain from one place, one five-and-dime, one bus ride to the next. The overarching point of these accounts is that the Jim Crow order was always disjointed.

Reed seeks to show that race never took on a life of its own. The rhetorical power of racial allegory—the notion that the power structure was impenetrably white over black—is insufficient as historical explanation because it assumes ideological uniformity. It is also insufficient for wrestling with political and cultural change after Jim Crow. In one relevant episode, Reed recounts how he almost beat a man who followed and harassed him and his wife in Fayetteville, North Carolina, in 1970—something that might have carried deadly consequences just a few years earlier.

Reed has long argued that race is historically contingent. Racism, he wrote in 2000, “is not an affliction; it is a pattern of social relations. Nor is it a thing that can act on its own; it exists only as it is reproduced in specific social arrangements, in specific societies, under historically specific conditions of law, state, and class power.” The point is not to play into a liberal narrative of inevitable progress. The point is that social, political, and economic conditions generate the circumstances of our everyday interactions. The South presents these arguments in autobiographical terms. In the incident above, the man in Fayetteville was confident in his own dominance, but Reed was armed with the knowledge of legal recourse that was now available to him as a matter of right. Still, Reed’s perspective is provisional and incomplete. Since reading about this encounter, I have wondered what would have happened if it were just his wife walking alone, or if it was a cop following them instead.

Like Reed, my parents were born long enough before the fall of Jim Crow to know what it was like in practice. My father is a native Mississippian whose early years were spent picking cotton with his siblings and father, a sharecropper in Coahoma County; my mother, born and raised in Memphis, was among the first students to integrate her high school. My mother resents driving through Mississippi to this day because of a brick that came hurling through the window of her parents’ sedan on the way back from a family trip to Greenville, Mississippi, in the late 1960s. When they hear people say nothing has changed, they have recounted these episodes with a mix of bemusement and ambivalence. I told my dad I was reviewing two books on the South before and after the Jim Crow era, and in casually asking him about what this period meant for him, he cautioned that I should see any wisdom he gave as limited by the distance of memory and change. Even so, I recall his insistence that everyone more or less accommodated Jim Crow’s rules and norms. The ability to choose to violate them depended on a host of factors including place, gender, and class position. My mother and her family wouldn’t have dared, for instance, turning the car around to find out who tossed that brick.

Read the entire review here.