Turning away from past errors requires more evangelical theology—not less

The observance of Black History Month each year raises a challenging question: Why did white evangelicals oppose the civil rights movement in the 1960s?

This is an uncomfortable question for evangelical Christians such as myself—and it has only become more uncomfortable due to books such as Anthea Butler’s White Evangelical Racism, who suggests that a defense of racial injustice is a longstanding and intrinsic part of white evangelical theology.

This is a serious charge, if true, because it suggests that white evangelical theology—and maybe, in the opinion of exvangelicals, Christian theology itself—needs to be abandoned if we wish to repent from racism.

But a closer examination of the historical evidence will show that the cause of white evangelical opposition to the civil rights movement was not a flawed gospel but rather a flawed politics that distorted many white Christians’ application of the gospel. Many white evangelicals at the time saw clearly that the gospel compelled them to advocate for desegregation. They just had trouble bringing themselves to do this in practice.

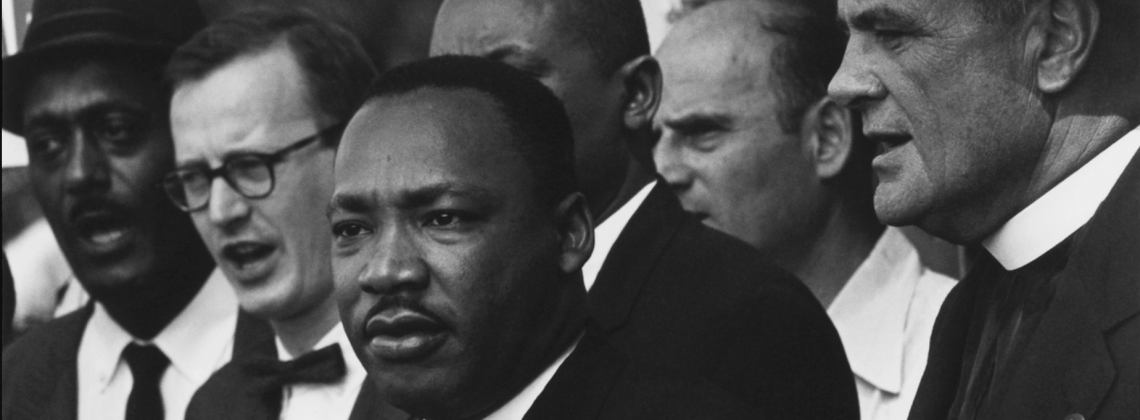

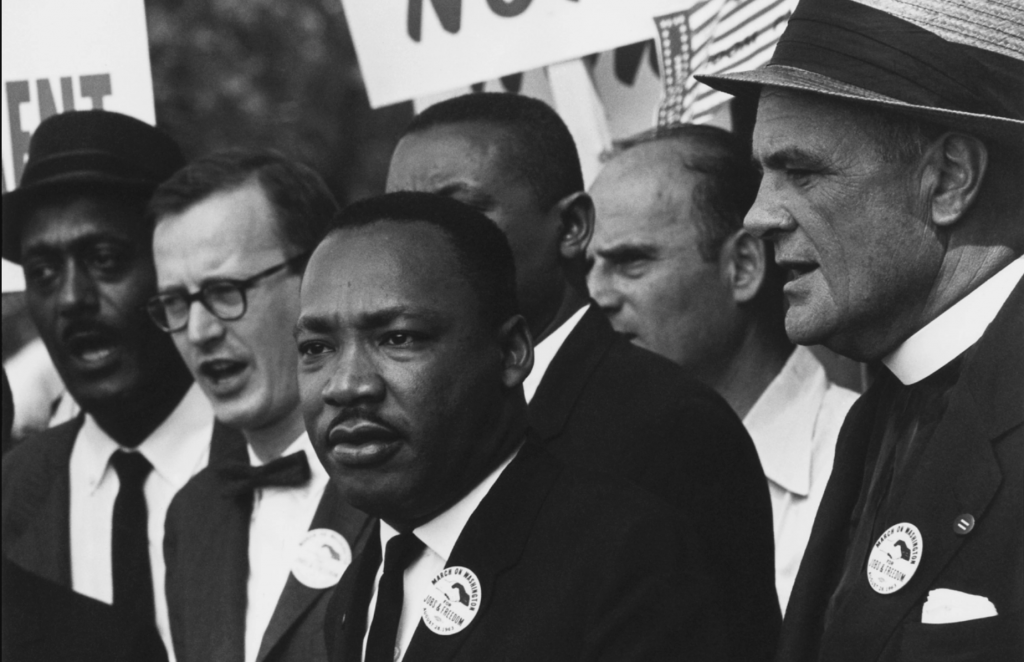

When Martin Luther King Jr. and other civil rights activists began a grassroots protest against racially discriminatory policies, many white evangelicals, especially those associated with evangelical institutions in the northern Midwest, insisted that they favored desegregation. In 1951, three years after President Harry Truman desegregated the US military, the National Association of Evangelicals passed a resolution calling for “equal opportunities” for both Blacks and whites in housing, education, wages, and commerce. Two years later Billy Graham desegregated his evangelistic crusades, insisting that Blacks and whites could sit next to each other even in southern states that still enforced segregationist laws.

When the Supreme Court issued a unanimous decision in favor of school desegregation in Brown v. Board of Education (1954), even the Southern Baptist Convention endorsed the ruling. Graham also lauded the court ruling, declaring in 1956 that “the Bible speaks strongly against race discrimination.” In 1957, Graham invited Martin Luther King Jr. to lead a prayer at his New York City crusade—an invitation King accepted.

Yet white evangelicals’ support for desegregation laws was always tepid and cautious; it rarely went much beyond the official pronouncements of both major political parties. While Graham publicly welcomed the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board, he privately expressed his hope to President Dwight Eisenhower that the Supreme Court would “go slowly” in advancing the cause of civil rights in order to avoid creating a backlash or jeopardizing the fragile coalition of moderate-minded southerners who supported the Eisenhower administration’s cautious approach.

Graham took this view at the time partly because he and many other white evangelicals viewed racial discrimination as a problem that the gospel, not the government, could solve. “Forced integration will never work,” Graham wrote in 1960. “You cannot make two races love each other and accept each other at the point of bayonets.” Instead, what was needed was a “spiritual and moral awakening.”

Graham and other evangelicals therefore devoted far more attention to fighting communism—a movement they believed impeded the spread of the gospel (the real key to moral change, in their view)—than they did to fighting racial discrimination.

In turn, white evangelicals’ anticommunism led them into alliance with conservative government officials who warned that civil rights leaders, including King, were influenced by communists.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Christianity Today published several anticommunist articles by FBI director J. Edgar Hoover, even though he was not an evangelical. And in 1964, Christianity Today approvingly quoted Hoover’s assessment that King was the “most notorious liar in the country.”

White evangelicals’ strong faith in American anticommunist policy made it difficult for them to accept the possibility that American policy might also be racially unjust. And their commitment to upholding American law prompted them to quickly condemn civil rights activists’ strategy of civil disobedience as unbiblical and unwarranted.

In essence, evangelicals’ claim that only the gospel could change racial attitudes prompted white evangelicals to focus their political activism primarily on removing impediments to the preaching of the gospel (such as communism), which in turn led them into alliance with anticommunists who opposed civil rights—and which therefore gave them an excuse to condemn those who were working on behalf of racial justice.

American white evangelicals of the 1950s and 1960s were so focused on fighting external evils such as secularism and communism—and they had so much confidence in the power of individual conversion to solve sin problems—that they failed to realize the extent of the injustice perpetrated by white Christians.

They didn’t have to abandon the gospel to realize this truth. Instead, they merely needed to listen to African American Christians. The problem was not that their confidence in the power of the gospel to change lives was too strong; it was rather that their vision of the church was too small, since it didn’t leave much room for the prophetic voices of African American Christians. Likewise, their estimate of the amount of repentance that would be required from white Christians was far too low.

The Protestant Reformation had been launched with Martin Luther’s proclamation that “the entire life of believers” was to “be one of repentance.” But American white evangelicals of the mid-twentieth century accepted a political ideology that allowed a focus on the external evils of secularism and communism to blind them to the sins inside the church. A valid claim that only the gospel can really change people’s hearts became, in the mouths of mid-twentieth-century white American evangelicals, an excuse for doing almost nothing about injustice among themselves as they waited for the gospel to do its work.

They failed to grapple with King’s assertion that even if “the law cannot change the heart,” it “can restrain the heartless.” As King said, “It may be true that the law cannot make a man love me but it can restrain him from lynching me; and I think that is pretty important also.”

In 2018, Christianity Today apologized for its opposition to King and the civil rights movement. By that point, all of the editors who had written against King had long since passed away, but the magazine’s new leaders wanted to take the first step in addressing the wrongs of the past.

Numerous other white evangelicals are also engaged in acts of public apology and repentance for the racial sins of their congregations and institutions. But to avoid repeating the past, white evangelicals need to realize that opposition to the civil rights movement of the 1960s was not merely the result of racism; it was also the result of a commitment to a political vision that focused too much on external rather than internal sin. Embracing a politics that focuses almost entirely on evil as external to ourselves runs the risk of making a similar error. Acting as if structural evil cannot exist in the church or among converted people means losing touch with the principles of the gospel in the same way that some white American evangelicals of the 1960s did.

The solution to this problem is not to abandon evangelical theology or dismiss it as racist. Instead, the gospel is desperately needed more than ever. But this time, white evangelicals need to apply its precepts more fully and not just use it as a justification for avoiding real repentance.

Daniel K. Williams is a professor of history at the University of West Georgia and the author of several books on religion and American politics, including God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right and The Politics of the Cross: A Christian Alternative to Partisanship. He is a Contributing Editor at Current.