Sometimes the book that’s banned is the one that must be taught

The video is in a grainy black and white, taken from a home security system, but what happens on the seconds-long film is absolutely clear: A masked man steps up to a porch and douses a Pride flag with accelerant, then lights the flag on fire. Turning to the camera, he offers up a quick Sieg Heil, then vanishes into the night. Moments later a passing stranger alerts the family sleeping inside, and they are saved from tragedy; although their flag is ruined, their home and lives are spared.

But the video, with its Nazi salute and potential hate crime, is unsettling, a reminder that white supremacists are increasingly active in my hometown of Newberg, Oregon. The Halloween night Pride flag incident happened across the street from the Christian college where I’ve taught for several decades. This event is not a one-off: A white supremacist group, the Proud Boys, rallied at Newberg’s town square in September 2021, and have made repeat visits since then. The Rose City Nationalist Club unfurled a “no political solution” flag on an overpass in town, while also showing up at a rally for local and county conservative candidates this fall.

To those who have been paying attention, their presence seems inextricably linked to a decision by our local public school board in September 2021, when a new majority of directors crafted a policy forbidding Black Lives Matter and Pride flags from classrooms. Although that policy was ruled unconstitutional in September 2022, the damage has been done—both in terms of cratering a once-vibrant school district, which lost over 100 educators in the past year, and by emboldening white supremacists in our community, including racist incidences so blatant that Newberg made national news several times (see here and here).

The white power ideologies taking hold in parts of my community reflect national trends. The Anti-Defamation League reports that 2021 had the highest ever recorded cases of anti-Semitic harassment, and recent public figures appear much more emboldened to express anti-Semitic sentiments on social media, including former President Trump, who dined with known white supremacist Nick Fuentes in November. This fall a number of news outlets reported on the rise of Christian nationalism in the U.S., with at least one evangelical press having few qualms about publishing The Case for Christian Nationalism by Stephen Wolfe.

Discourse about white supremacy and Christian nationalism can feel mostly theoretical if you are Christian and white and not directly impacted by its hateful ideology. What is unfolding in Newberg provides an important example of what happens when the theoretical becomes real. Proud Boys waving their flags close to campus, as well as a crumbling school district and its alt-right school board, make comfortable inaction no longer tenable, especially given the biblical call to love God by loving our neighbors, including those targeted by nativist hate.

As one person, I feel impotent to stop white supremacists from finding traction here, with few antidotes available to me beyond voting, attending school board meetings, writing elected officials, and praying. Institutions have far more power, though, and Christian colleges especially can provide a necessary antidote to this moment we’re in. But they must have the fortitude to respond rather than remaining silent, calling out Christian nationalists and neo-Nazis in the communities where they have significant influence.

Christian college educators can also make curricular choices that challenge the toxic ideology embodied in Christian nationalism. When slim university budgets make it tempting to cater to constituents in the thrall of right-wing media, and when administrators fear accusations of “wokeism,” institutional courage is needed to turn white supremacists away from our literal and figurative doorsteps. On my most optimistic days, I believe Christian institutions will rise to this challenge, and will recognize that providing a bulwark against this hate is a matter of faith, even when—especially when—doing so might seem to threaten the bottom line.

Because my home community has experienced the encroachment of white nationalists firsthand, it seems we might be a test case for what is happening across the United States, where alt-right candidates win local elections, then create policies that purportedly intend to return communities to some former greatness: by abolishing Black Lives Matter and Pride signs, by constructing policies that harm already marginalized populations, and by banning curricula deemed too woke for schools and libraries.

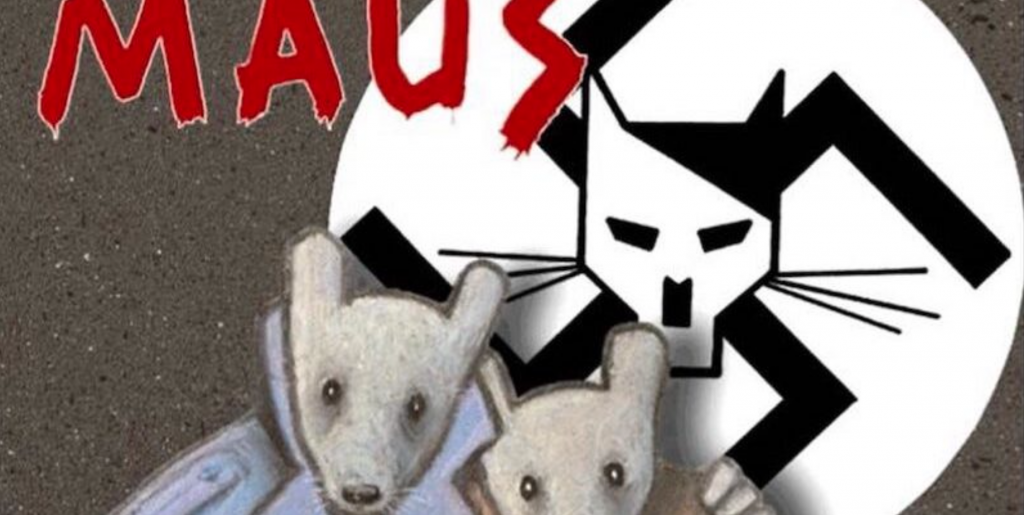

One example of the latter is the banning of Art Spiegelman’s Maus, which a Tennessee board unanimously voted earlier this year to remove from its schools for nudity and portrayals of violence. Maus is about the Holocaust. Of course it will be violent. But the book, featuring the writer’s parents, both Holocaust survivors, is a work that bears witness to the evils of violent totalitarianism and dehumanization occurring in relatively recent history. The graphic memoir has often been used in schools to educate young people about the Holocaust, in part because of its accessibility and its ability to provide a personal connection to the Holocaust’s horrors—horrors that traumatized not only survivors but their descendants as well.

At George Fox University we were on the cusp of deciding on texts for our first-year writing students when Maus’ banning hit the news. The writing class, called Caring for Words, is part of our university’s general education package, the Cornerstone Curriculum, which itself is built on the ideals of character development and Christian formation. It might seem counterintuitive to choose a book about the Holocaust for a course devoted to Christian formation, especially one written by an author who identifies as a non-practicing Jew.

Yet the decision to teach Maus felt exactly right, one way we could respond to the surging Christian nationalism taking hold in our community. Reading Maus with my first-year students opened space to reflect on what was happening just blocks from campus and in communities nationwide. Discussions about the book’s banning in other schools led to wider considerations of whose stories we are willing to hear, why books like Maus are being met with resistance, and how book bans have historically been one step on the path to totalitarianism. We talked about the complicity of some Christians during the Holocaust, and how people of faith should respond to the Christian nationalism gaining traction here and now.

I’m not so idealistic as to believe that including Maus in our first-year curriculum will be all that’s needed to turn white nationalists away from our community, nor that curriculum choices at other universities will stop a movement that is gaining too much momentum. But it’s time for Christian institutions to engage directly with white nationalism. Intentionally choosing books that have been targeted by Christian nationalists might be one way to explicitly name the dangerous ideologies blooming in our communities, even when doing so might offend some constituents upon whom we rely for funding.

Our country is at a dangerous inflection point, reflected in the turmoil upending my once-peaceful Quaker town, where white nationalists feel emboldened to burn symbols of inclusion and raise swastika flags. Christian universities have significant tools available to them to combat those who would deny the existence in others of the imago dei, the very image of God. If we truly exist to form students to embrace a Christian worldview, we must be sure that this worldview is truly that—and not one limited to a specifically nationalist ideology.

Melanie Springer Mock is Professor of English at George Fox University. Her books include Worthy: Finding Yourself in a World Expecting Someone Else (2018), and If Eve Only Knew: Freeing Yourself from Biblical Womanhood to Become Who God Expected You to Be (2015). Her essays have appeared in Christian Feminism Today, Literary Mama, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Brain, Child, and The Oregonian, among other places. Much of her work focuses on her experiences parenting, feminism within Christian context, and writing theory.

Thank you for this pertinent reminder. May those of us at Christian colleges have the courage to work toward peace and justice so that all of God’s image bearers are treated with dignity.