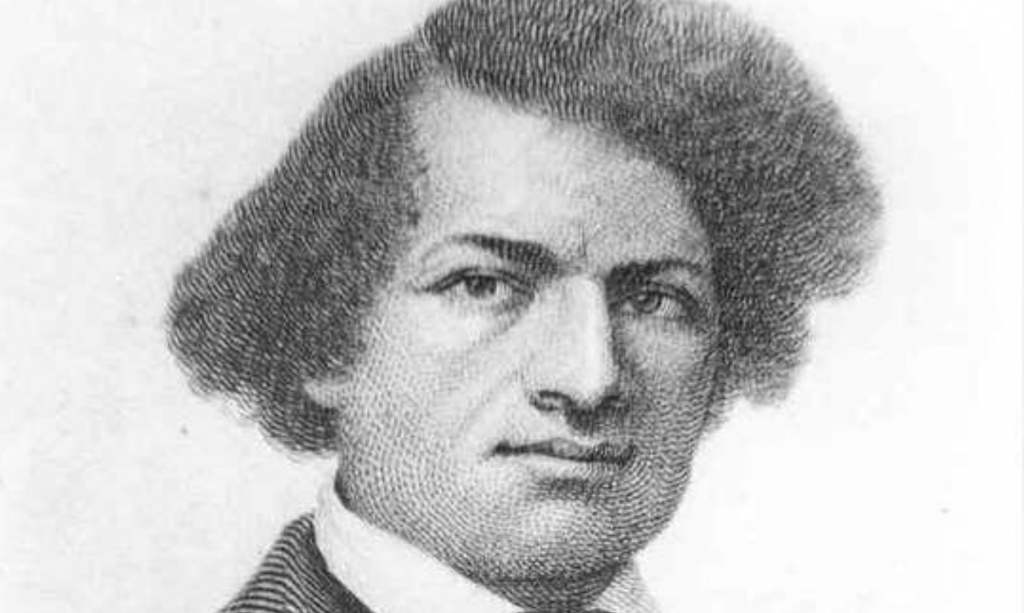

What can we learn about liberal arts education from Frederick Douglass and the formerly enslaved?

I’ve been teaching A Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave in my United States history survey course at least once a year for the last quarter century. During that period I have also taught a semi-regular course on the Civil War and Reconstruction. This semester, I am teaching these courses in back-to-back hours on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday mornings.

Last Friday I had one of those serendipitous moments when the readings for both classes—Douglass’s Narrative and Eric Foner’s A Short History of Reconstruction—converged around the historic relationship between education and freedom.

American slavery was a brutal institution, and Douglass’s narrative makes that clear. I assign the Narrative, in part, because I want my students to understand the physical nature of slavery. But my students cannot miss the psychological and social ramifications inherent in the system of human bondage that Douglass toiled under. As we talk about these things in class, we always return to Sophia Auld, the slave mistress who taught Douglass to read, only to be rebuked by her husband, Hugh, for doing so. According to Hugh (whose words were recorded by Douglass in the Narrative), “learning would spoil the best nigger in the world.” If Douglass learned to read, Hugh said, “there would be no keeping him.” Learning “would do him no good, but probably, a great deal of harm—making him disconsolate and unhappy.”

Hugh Auld was partially right. Education did make Douglass unhappy and disconsolate. At one point in the Narrative he grows so depressed that he wishes he had never learned to read in the first place. After the slave-breaker Mr. Covey is finished with him, Douglass writes, “my intellect languished, the disposition to read departed . . . the dark night of slavery closed in upon me; and behold a man transformed into a brute!”

Douglass’s depression is so acute in the Narrative because he knows from experience that reading can take him places, even if only for the moment and only in his imagination. As Levar Burton taught millions of children through the PBS show Reading Rainbow, “I can go anywhere. Take a look, it’s in a book.” Douglass experienced the power of education and its connection to intellectual, and eventually physical, freedom.

At this point in the conversation with my students I remind them that earlier in the semester they read Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography. Anyone familiar with the Autobiography knows that Franklin offers-up his own story as a testament to what would later become known as the American Dream. For generations, the Autobiography served to inculcate American values in schoolchildren. How does one “make it” in America? Franklin teaches us that one succeeds in this country through reading, education, the mutual exchange of ideas with like-minded learners (as exemplified in his “Junto”), hard work, and self-improvement.

In some ways, Franklin and Douglass are a lot alike. They both want to experience the promise of America. But only one of them is able to achieve it, due to the color of his skin and the circumstances of his birth. The fact that Douglass cannot pursue a life of American self-improvement through education is, in many ways, the essence of slavery. And the United States is still living with its consequences.

Before I taught Douglass’s Narrative to three different groups of students last Friday, I led a discussion of Foner’s chapter, “The Meaning of Freedom.” The chapter covers the various ways in which the formerly enslaved sought to practice freedom in the months and years immediately following their emancipation. “In countless ways,” Foner writes, the newly freed slaves sought to overturn the real and symbolic authority whites had exercised over every aspect of their lives.”

Freedmen and freedwomen formed their own churches and benevolent societies and sought to gain economic independence through the acquisition of land. And they had a “seemingly unquenchable thirst for education.” Like Douglass, and like Franklin before him, they understood that literacy and learning were perhaps the most important part of their transition from slavery to freedom. And when the racist white Democrats in the South (and President Andrew Johnson) wanted to limit the social advancement of the freedmen and freedwomen, they sought to cut government funding for Black education. (See, for example, Andrew Johnson’s veto of the Freedmen’s Bureau Act in 1866 or Southern attempts to keep the formerly enslaved out of white schools in the 1870s—a practice that continued through the 1960s.)

My middle-class college students—most of them white—will never experience anything close to what Frederick Douglass and the Reconstruction-era freedmen and freedwomen experienced in nineteenth-century America. I want them to understand their privilege. By teaching them about Douglass and Reconstruction, I want them to be better citizens, to understand the meaning of American slavery, and to have a deeper understanding of contemporary race relations in America.

But I also want them to learn something about the power of education. I want them to develop a greater appreciation for the liberal arts education they are receiving and not take it for granted. Liberal education is, quite literally, “education for freedom.” Though my students will never have to suffer under the whip of Mr. Covey, the moment they let their intellect languish and their desire to read depart is also the moment they too enter a kind of slavery.

John Fea is Executive Editor of Current.

Amen.

Thanks, John.