Putting the “history” back into “activist history”

I am often asked if I have ever debated David Barton on the question “Was America founded as a Christian nation?” I have not. Barton is a popular conservative evangelical political operative who through his organization Wallbuilders uses the American past to promote his political agenda. His goal is to make America Christian again—to restore the United States to its supposed Judeo-Christian roots.

David Barton claims he is a historian. He is not. He is an activist. He has little interest in understanding the past in all its fullness and complexity. He cherry-picks facts and quotations in service of his Christian nationalism. The past is only useful if it is changing the world in the way David Barton wants to change it. As American Historical Association president James Sweet recently reminded us, the historian Lynn Hunt described this approach to the past as “short-term . . . identity politics defined by present concerns.” Bernard Bailyn once called “indoctrination by historical example.”

I don’t think a debate with Barton would be very productive. Sure, I might call him out on factual errors in the way Warren Throckmorton and Michael Coulter did in their book Getting Jefferson Right: Fact Checking Claims about Our Third President. But more often than not Barton quotes accurately from the documents he displays to his audiences and posts on his website. For example, Barton might try to score a “gotcha” moment in such a debate by quoting from George Washington’s farewell address, in which the first president described “Religion and morality” as the “great Pillars of human happiness, these firmest props of the duties of Men citizens.” My on-stage response would probably go something like this: “Yes, of course George Washington said this. He also believed this.” But I would also try to put Washington’s words, and all of David Barton’s cherry-picked quotes, in a larger context. I would ask him whether the founders’ comments about religion, written in an eighteenth-century context where Protestant Christianity was the only game in town, are still useful in our twenty first-century pluralistic society. He, of course, would argue that they are still useful. But by turning the debate from what the founders believed about the relationship between religion and the republic to whether the founders were right about such beliefs, or whether such claims should be applied today, the debate would cease to be about history and become a debate over politics. As Sweet writes, “History is not a heuristic tool for the articulation of an ideal imagined future. Rather, it is a way to study the messy, uneven process of change over time. When we foreshorten or shape history to justify rather than inform contemporary political positions, we not only undermine the discipline but threaten its very integrity.”

There is a difference between history and the past. Sweet argues that those concerned only with how their work will advance this or that cultural or political movement in the present would be “better served taking degrees in sociology, political science, or ethnic studies.” All these disciplines turn to the past as prologue. Historians, of course, are also concerned about the past as prologue, but we are constantly moving back and forth between the past and the present in a way that no other discipline does. A colleague of mine says that this kind of constant “travel” between the past and the present often gives the historian “intellectual jet lag.” If historians are not explaining “how we got here” or how the past has shaped present-day life, we are little more than antiquarians.

But sometimes historians travel to the past and stay awhile. We seek to understand the past on its own terms. We listen to the voices of those who inhabit what E.P. Hartley called a “foreign country”—a place where they “did things differently.” We immerse ourselves in the culture of the past and try to bring that lost world to life for our readers and students. When we are only looking for something in the past to help our present-day agendas we fail to do justice to the humanity of those who lived before us. Our own interests, our own location, and the prevailing cultural climate of the present might inspire us to get to know certain kinds of actors in these “foreign countries,” but we must explain them to audiences on their terms, not ours. As one of my favorite historians, Laurel Thatcher Ulrich, once put it, “The value of any activity is determined by its meaning to the participant, not to the observer.” Historians take Ulrich’s claim seriously. Other disciplines will not give priority to this kind of thinking about the past.

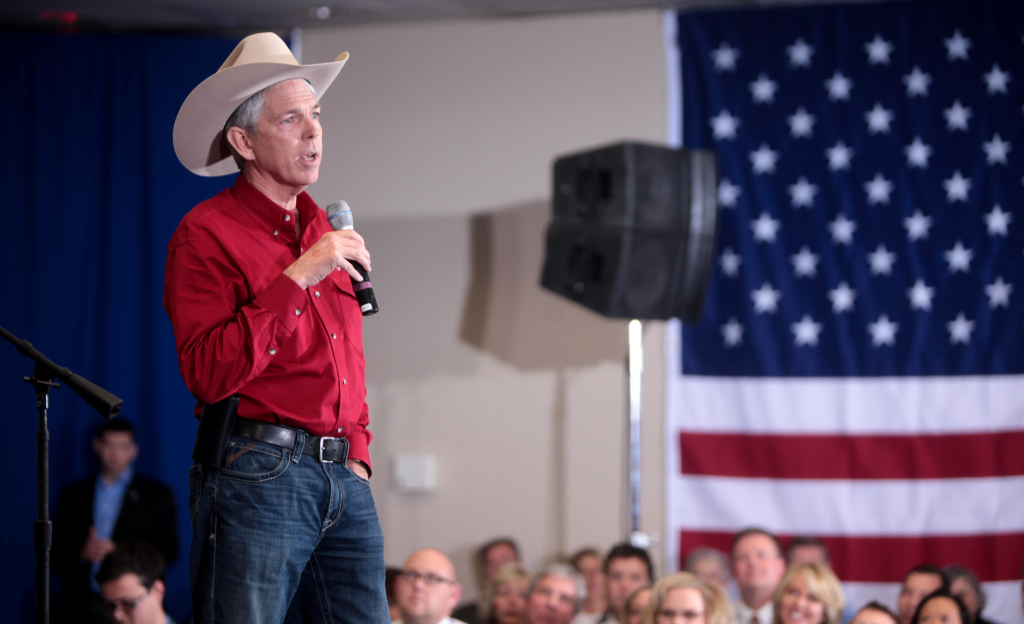

Those who write and teach about the past as a foreign country are not trying to seek apolitical objectivity. An entire generation of historians who read Peter Novick’s 1988 book That Noble Dream: The ‘Objectivity Question’ and the American Historical Profession knows that objectivity is impossible. All history is, in some ways, political. As Joan Scott recently argued in The Chronicle of Higher Education, “The study of previously neglected subjects required the study of the politics of history. And the study of the politics of history called into question the neutrality and dispassion the discipline had long endorsed.” I agree, in part, with Scott. But what happens when one’s political opponents also reject such “dispassion”? I am sure David Barton would agree completely with Joan Scott’s words here. So would Pennsylvania gubernatorial candidate Douglas Mastriano, former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, and Christian Right political operative Ralph Reed. All three of these conservatives have PhDs in history and appeal regularly to the past in their political work.

When the practice of history becomes solely about raiding the past for useful arguments, not only are we in danger of falsifying the past—we are also failing to provide our students the chance to learn certain skills that are transferable to their callings as citizens. In his masterful work Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts, Stanford education professor Sam Wineburg, the country’s leading authority on the teaching of historical thinking skills, argues convincingly that it is the strangeness of the past that has the best potential to change our lives in positive ways. Those who are willing to acknowledge that the past is a foreign country—a place where they do things differently than we do in the present—set off on a journey that has the potential to make the world a better place. An encounter with the past in all its fullness, void as much as possible of present-minded agendas, can cultivate democratic virtues in our lives. Such an encounter teaches us empathy, humility, and selflessness. We learn to remove ourselves from our present context to encounter the culture and beliefs of the lost worlds of the past in which we immerse ourselves.

For example, most of my students are white. I want them to encounter non-white voices in the past and learn to listen to them on their terms. In the process, my white students just might be cured of their narcissism—a view of the world that places them, not others, at the center. While seeing the world with the self at the center is a normal way to see the world if you are an infant or toddler, it is a very immature way of viewing things if you are an adult. History, to quote historian John Lewis Gaddis, “dethrones” us “from our original position at the center of the universe.” As Wineburg puts it, history “educates (‘leads outward’ in the Latin) in the deepest sense.” As we begin to see our lives as part of a human community made up of both the living and the dead, we may also start to see our neighbors (and our enemies) in a different light. We may want to listen to their ideas, empathize with them, and try to understand why they see the world the way they do. We may want to have a conversation (or two) with them. We may learn that even amid our differences we will have a lot in common.

These are the democratic practices I want to teach my students. I believe—both from conviction and experience—that history is the best way to do it. Perhaps this makes me an activist as well.

John Fea is Executive Editor of Current

OK–Permit a perspective from a historian of the American South who grew up under Jim Crow. History was important for my generation of southerners because it was a battlefield, and one not of our own choosing. Jim Crow, the Cult of the Lost Cause, the whole shebang, was about using a version of history to justify present-day injustice. Thus, for instance, the lesson of Reconstruction, I was taught in my youth, was that it was dangerous to apply airy-fairy theories about human equality to the real, God-ordained world of white supremacy. Dismantling Jim Crow was thus perforce a historical project. Beginning with historians like my mentor C. Vann Woodward, southern history began to get complicated and multivalent, with voices long dismissed brought to the table. Indeed, the Otherness of the past became itself an activist weapon, as the supposed eternal verities of Jim Crow were revealed to have a history in which alternatives had been foreclosed not by immutable moral laws but by messy contingency, and that what had been made in historical time could also be remade in historical time. Yes, this was “activism”–but it worked its will by doing precisely what you advocate historians do–appreciate the difference between past worlds and our own, and by so doing disenthrall ours from the dead hand of the past. It worked in much the same way as, say, Beth Allison Barr’s work does in undercutting the alleged Eternal Verities of patriarchal theology by revealing alternative possibilities within the two-thousand-year-old Christian tradition. Well-done history opens up possibilities that the gate-keepers, be they the CBMW or the UDC, insist on keeping closed.

What drew me into history was its explanatory power—the why of things as they are. And history as John describes its method is doing so with an open mind. Not unbiased because that is humanly impossible, but aware of our biases and a conscious repression of them so as to hear the past as the participants might have heard it. You end up with nuance. And isn’t life nuance? A recent example for me is Malcom Gladwell’s latest book, The Bomber Mafia. Gladwell is not a historian but the book is a work of popular history. Yet he offers us an explanation for the massive destructive bombing of WWII. The nuance came for me after reading the book. The idea that war can be made more humane comes into real questioning. The war in Ukraine provides illustration of the problem.

Hi David: Great comment. I think Woodward did this well. Check out Jim LaGrand’s piece in our edited collection *Confessing History*, he makes a similar argument about Woodward versus what he calls a “preaching through history” approach. I have no major qualms with what you write here. But let’s also remember that Barton, Mastriano, Reed, and Gingrich also want to “reveal alternative possibilities” that the gatekeepers in the “secular academy” have kept closed.

Agreed. I think there are approaches to “history” out there that want to use the past to advance this or that agenda. This fails to understand the complexity of the individual actors in history. Perhaps some historians should stop and think about whether they would want to be portrayed in the one-dimensional way that so many historians treat their subjects today.