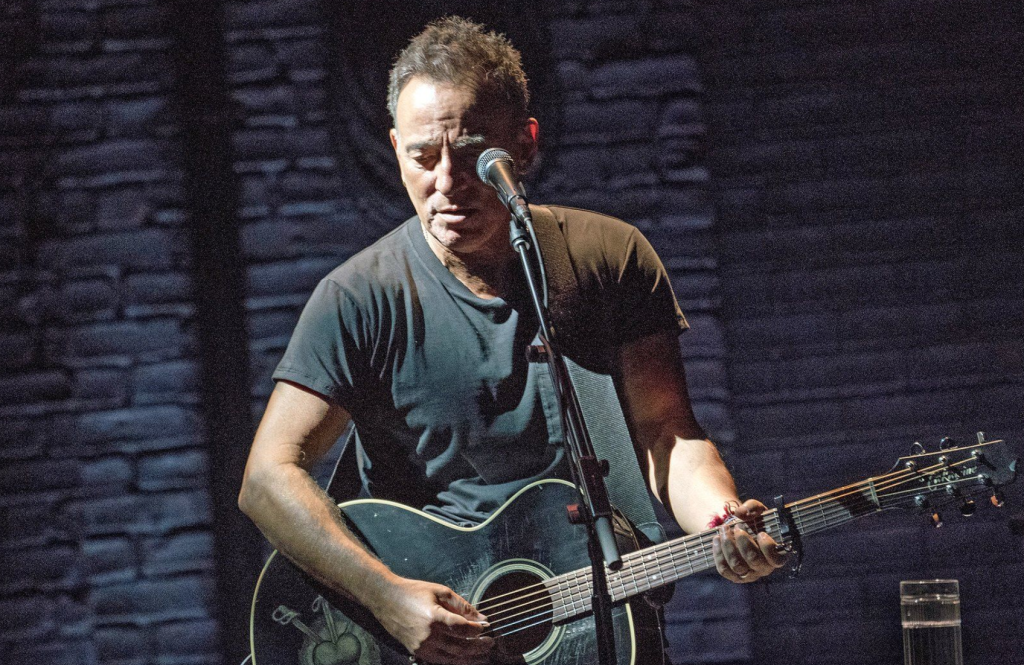

Over the weekend I lamented the possibility that I might not be able to see Springsteen on his upcoming tour. Tony Norman, an opinion writer at the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and a Current contributor, has my back and the backs of all disgruntled Springsteen fans. Here is a taste of his column “Price gouging on the end of town?“:

There’s a line that comes immediately to mind about the latest kerfuffle between Bruce Springsteen and Ticketmaster that has seen tickets for his upcoming tour surge as high as $5,000 a pop:

“Well, I got a job and tried to put my money away/ But I got debts no honest man can pay.”

Hardcore fans, especially those desperately trying to get tickets to a Springsteen show in the era of dynamic pricing, will connect with those lyrics from “Atlantic City,” arguably the best cut from his spare and haunting 1982 masterpiece “Nebraska.”

We’ve all seen the headlines in recent days about ridiculously high ticket prices “angering” the Boss’ longtime working- and middle-class fans who’ve waited to buy tickets since his last tour seven years ago.

They want to know why it should cost several paychecks to cover one or two tickets plus gas, a dinner, parking, and a souvenir t-shirt or two.

Why are true fans who’ve been following him for more than five decades expected to be saddled with Ticketmaster debt “no honest man can pay?”

The angriest of them took to social media denouncing both Springsteen and Ticketmaster. You can’t just blame the algorithms, they said. Someone saw the first Springsteen tour in seven years as a golden opportunity to make killing.

“I have nothing whatsoever to do with the price of tickets,” E Street Band guitarist Stevie Van Zandt wrote on Twitter.

Springsteen fans know this. They aren’t naïve about supply and demand. But they’re still angry because they know they’re being ripped off. They’ve done the math: According to every actuarial table, Springsteen, 73, is likely in the twilight of the touring phase of his career.

For older boomers, this may be their last chance to see him before the Grim Reaper comes knocking on their doors, too. Consequently, everyone expects to pay a premium to see the Boss at this point, especially if he’s only averaging two tours a decade.

No one expects him to be doing 3-hour shows well into his 80s like some Jersey Turnpike version of Mick Jagger. Still, seeing Springsteen shouldn’t require refinancing a mortgage just to sit in the nosebleeds.

And this:

The one thing that everyone of every political stripe agrees on is that Ticketmaster has done nothing to deserve the windfall it receives as the middleman in its near monopolistic ticket empire. What did Ticketmaster ever contribute to Springsteen’s music to deserve the obscene profits that scams and gimmicks like dynamic pricing generate for its bottom line?

And why can’t artists and venues to be trusted to work out ticket prices with input from fans who will ultimately buy the tickets? Why is a middleman like Ticketmaster allowed to insert itself into the relationship? Why is another for-profit business entity that charges a litany of absurd and redundant fees allowed to disrupt the relationship between artists and fans?

This is a humiliating and ridiculous situation, but that’s capitalism for you. For some reason, the American political and business class is perfectly comfortable with brutal and stupid market practices that are self-defeating in the long run. No one is fooled by what’s going on. We just tolerate it until the day we won’t tolerate it anymore.

Read the rest here.

When Bill Graham closed the legendary concert venues the Fillmores East and West in the summer of 1971–for, among other reasons, bands charging too much–tickets were typically $3 to $5 for two or three top acts. Live music gravitated to festivals and stadiums.

Two years later, on July 31, 1973, I saw the Band and the Grateful Dead at Roosevelt Stadium in Jersey City, which had a capacity of 24,000. I was sitting in the stands between first base and center field, and we could see everyone’s faces, it was so small.

We had debated whether to even go because the tickets were so expensive: there were no weird extra “fees” back in those days, but still, $6.00 was an unheard of amount of money for a concert! Even with two groups! In 1973 the federal minimum wage was $1.60, and, being a high school student employed as a lab assistant by my grad student brother-in-law, I doubt I made anything close to that.

$6.00 in 1973 would be about $40.00 now.