The 87-year-old agrarian writer lets it rip in his forthcoming book The Need to Be Whole: Patriotism and the History of Prejudice. Here is a description of the book, which is scheduled to appear in early October:

Wendell Berry has never been afraid to speak up for the dispossessed. The Need to Be Whole continues the work he began in The Hidden Wound (1970) and The Unsettling of America (1977), demanding a careful exploration of this hard, shared truth: The wealth of the mighty few governing this nation has been built on the unpaid labor of others.

Without historical understanding of this practice of dispossession—the displacement of Native peoples, the destruction of both the land and land-based communities, ongoing racial division—we are doomed to continue industrialism’s assault on both the natural world and every sacred American ideal. Berry writes, “To deal with so great a problem, the best idea may not be to go ahead in our present state of unhealth to more disease and more product development. It may be that our proper first resort should be to history: to see if the truth we need to pursue might be behind us where we have ceased to look.” If there is hope for us, this is it: that we honestly face our past and move into a future guided by the natural laws of affection. This book furthers Mr. Berry’s part in what is surely our country’s most vital conversation.

Back in February, New Yorker editor Dorothy Wickenden got an advanced copy of The Need to be Whole. Here is a taste of her response to what she read:

In “The Need to Be Whole,” he argues that the problem of race is inextricable from the violent abuse of our natural resources, and that “white people’s part in slavery and all the other outcomes of race prejudice, so damaging to its victims,” has also been “gravely damaging to white people.” The book’s subtitle is “Patriotism and the History of Prejudice.”

Before sending me the manuscript, Berry wrote that he belongs to “a tiny side but no party.” Indeed, this “pondering and ponderous book,” as he calls it, contains something to offend almost everyone. “A properly educated conservative, who has neither approved of abortion nor supported a tax or a regulation, can destroy a mountain or poison a river and sleep like a baby,” he writes. “A well-instructed liberal, who has behaved with the prescribed delicacy toward women and people of color, can consent to the plunder of the land and people of rural America and sleep like a conservative.”

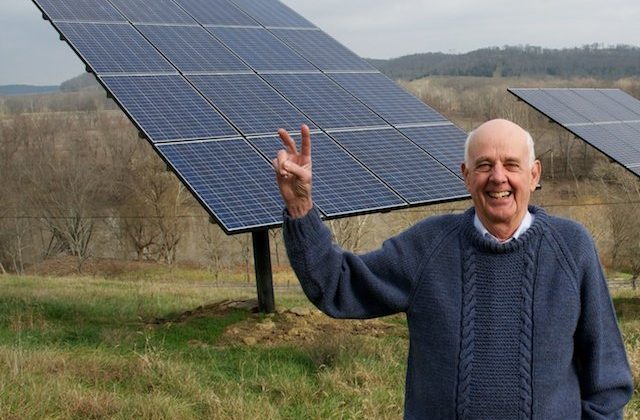

Thomas Friedman, of the Times, is scolded for a preening column in which he calls himself a “green capitalist” and blames Congress for not cracking down on coal, oil, and gas producers. Berry observes, “The deal we are being offered appears to be that we can change the world without changing ourselves.” This kind of thinking enables us to continue using too much energy “of whatever color,” hoping that “fields of solar panels and ranks of gigantic wind machines” will absolve us of guilt as consumers. Which is not to say that Berry renounces the use of green energy. He posed for a photograph several years ago in front of the solar panels by his house, grinning and flashing a peace sign.

Berry summons writers, from Homer to Twain, who extended “understanding and sympathy to enemies, sinners, and outcasts: sometimes to people who happen to be on the other side or the wrong side, sometimes to people who have done really terrible things.” In this spirit, he offers an assessment of Robert E. Lee, whom he calls “one of the great tragic figures of our history.” He presents Lee as a white supremacist and a slaveholder, but also as a reluctant soldier who opposed secession and was forced to choose between conflicting loyalties: his country and his people. “Lee said, ‘I cannot raise my hand against my birthplace, my home, my children,’ ” Berry writes. “For him, the words ‘birthplace’ and ‘home’ and even ‘children’ had a complexity and vibrance of meaning that at present most of us have lost.”

Berry wants readers to hate Lee’s sins but love the sinner, or at least understand his motives. War, he suggests, begins in a failure of acceptance. He writes of exchanging friendly talk with Trump voters at Port Royal’s farm-supply store, a kind of tolerance that is necessary in a small town: “If two neighbors know that they may seriously disagree, but that either of them, given even a small change of circumstances, may desperately need the other, should they not keep between them a sort of pre-paid forgiveness? They ought to keep it ready to hand, like a fire extinguisher.” Without this, we risk conflagration: “A society with an absurdly attenuated sense of sin starts talking then of civil war or holy war.”

If readers were incredulous about Berry’s claim that a pencil was a better tool than a computer, it’s not hard to imagine how many will react to his plea that we extend sympathy to a general whose army fought to perpetuate slavery in America. Several of Berry’s friends urged him to abandon the book, anticipating Twitter eruptions and withering reviews. He writes, “My friends, I think, were afraid, now that I am old, that I am at risk of some dire breach of political etiquette by feebleness of mind or some fit of ill-advised candor.” He listened, and fretted, but kept going. “They are asking me to lay aside my old effort to tell the truth, as it is given to me by my own knowledge and judgment, in order to take up another art, which is that of public relations.” In a letter, he told me that he didn’t want to offend “against truth or goodness,” although the book “at times certainly does offend, I think necessarily, against political correctness.” Tanya crisply told him, “It’s too late for it to ruin your whole life.”

Jeff Bilbro, editor of the Front Porch Republic, a pro-Berry blog, offers a taste of what we can expect:

Strap in. I’m sure we will hear more about this book in the months to come.

Haven’t we all been taught to listen to our elders? 😉 Mr. Berry may offend one and all, mainly because we all, at one time or another, feel offended when confronted with truth. Our human pride can’t bear being told it is wrong. I look forward to reading the book.

Me too. Berry is a truthteller.