A time to listen

This past Friday afternoon, as the tidal wave of the Dobbs decision was washing over us all, the editors put out a call to friends of Current for brief responses to the moment—responses that might range from the personal to the analytical, from the prophetic to the meditative, from the left to the right. Hoping for two days’ worth of submissions, we received way more—a windfall of wit and wisdom, layered in no small amount of anguish.

Our forum “The End of Roe” will run through Thursday of this week. It will feature reflections from scholars, writers, pastors, professors, and activists who have been engaged in this most divisive and personal of issues for many years, some since the Roe decision itself. We hope that amid your own responses to this moment you will find this forum an aid to deepening understanding and fruitful action.

Please note that we’ve removed our paywall for the site through the end of this forum—The Editors.

***

Passing injustice down the chain

In a 1947 Negro Digest essay, Black lawyer and future Episcopal priest Pauli Murray explained “Why Negro Girls Stay Single.” She noted that in some cases Black men who were denied respect and meaningful employment by Jim Crow society took out their frustration on their partners. She summed up this aspect of human nature with the aphorism “Pa beats Ma, Ma beats me, and I beat the hell out of the cat.” When harmed by those with more power, we sometimes seek to regain control at the expense of those with less power.

To my knowledge, Murray did not publicly speak into abortion debates, but her saying struck me as descriptive of abortion dynamics in the United States. When pro-choice advocates sought abortion rights in the years before Roe, women couldn’t get a credit card in their own name. They faced widespread workplace discrimination even if they weren’t pregnant, and much more so if they were. Panels of doctors made abortion decisions for pregnant women, and those doctors were almost all men. The burdens of reproduction will always fall more heavily on women, but instead of mitigating that burden, American society had piled a large number of additional burdens on their backs. Some women used abortion to reclaim agency in the face of this injustice. Unfortunately, abortion passed that injustice down the chain to still more vulnerable unborn girls and boys.

Since Roe, many aspects of society have improved for women, but many inequities remain. The United States has one of the worst maternity leave policies in the developed world. American poverty disproportionately falls on women, children, and people of color. Women are far more often the victims of sexual violence.

As a Christian, I have been encouraged to see how many fellow Christians across the political spectrum have contributed time and money to assisting women in unplanned pregnancies and how many have been at the forefront of adoption. Simultaneously, I have been distressed to see how many pro-life Christians have resisted measures to expand maternity leave, combat poverty, or respond appropriately to accusations of sexual abuse.

The best case scenario is that the Dobbs ruling results in Americans of all political convictions increasingly seeking the flourishing of human life at every stage of Murray’s metaphorical chain. But whether it does is up to us.

Andrea L. Turpin is Associate Professor of History at Baylor University and author of A New Moral Vision: Gender, Religion, and the Changing Purposes of American Higher Education, 1817-1917 (Cornell, 2016). She is a recipient of a 2022 Louisville Institute Sabbatical Grant for Researchers for work on a book manuscript about how Protestant women’s organizations navigated the fundamentalist-modernist controversy of the early twentieth century.

***

Eros is a jealous god

When Politico published Justice Samuel Alito’s draft opinion, I felt surprising dread. I welcomed the prospect of this ruling, but I worried it would unleash rage.

Initially I was shocked by the Handmaid’s Tale role-players disrupting celebrations of the Mass. I grieved as protesters marched outside of Supreme Court justices’ homes, and as groups represented by Jane’s Revenge attacked crisis pregnancy centers.

I recognize that more of the same is likely to follow for several weeks, or months. God forbid that it boil for years. Still, these assaults speak volumes. Abortion is a bloody, violent act against defenseless life in the womb. Why should it shock us that any restriction of this violence provokes a violent response?

My hope is that Americans will understand Dobbs. It does not impose national limits on abortion. Rather, it returns the abortion debate to where it belonged: fifty state legislatures. Rather than imposing abortion policy from above, it gives fifty engines of democracy the charge to craft statewide policies that best express the will of each state’s citizens.

Will Dobbs lead to fewer abortions? I hope and pray it does. I am confident in the pro-life movement’s ability and eagerness to help as many pregnant women as will receive its help.

If people follow through on threats of increased violence, as issued by Jane’s Revenge, I hope they will be arrested, given a fair trial, and face justice if convicted.

Abortion is one of several points on which Christians face a choice between a culture of life and a culture of death. Sexual morality is another. Moralistic therapeutic deism is a third. Pope John Paul II said it most clearly, but even some atheists grasp how many lives are threatened when abortion on demand is the court-imposed norm nationwide.

Some churches tried to make peace with the sexual revolution fifty years ago, and many learned that Eros is no less jealous than the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob. Some stayed with Eros.

Millions of people invoke the name of Christ and disagree with me, and I know some of them as friends. I grieve when our differences strain our friendship, or our Christian communion. But they have chosen a place to stand, as have I, as we all will, one day or another.

Douglas LeBlanc is a veteran writer and editor living near Charleston, S.C.

***

Overturning Roe was a pro-life dream. The current political context is not.

The Supreme Court’s reversal of Roe v. Wade did what pro-life activists have sought for the past half-century, but not on the terms that the pro-lifers of the early 1970s had hoped. While the Dobbs decision has returned abortion policy to the states, it is not doing so as a part of the “culture of life” that early pro-life activists wanted. States now have the right to prohibit abortion (or expand access to it), but the unfortunate reality is that no state is likely to do what many politically progressive pro-lifers wanted to do in the early 1970s: couple abortion restrictions with expanded aid to pregnant women in the form of healthcare and childcare.

In the early 1970s, the pro-life message was frequently linked with New Deal and Great Society liberalism, and it was popular in some of the nation’s most strongly Democratic (and heavily Catholic) states, such as Massachusetts and Rhode Island. Conversely, the pro-choice message was popular with libertarian-leaning Republicans, such as Barry Goldwater. But Roe v. Wade set in motion a long process that changed these political alliances. As a result, Roe’s reversal last week came at a political moment when all of the states that will likely restrict abortion are Republican states that, in many cases, are also likely to restrict Medicaid and other social welfare and family leave policies that might assist women in caring for their children, while all of the Democratic states with more generous social welfare policies are also states that will probably expand funding for abortion.

For people who want more than a legal prohibition against abortion and who would thus like to see reductions in the abortion rate that result from policies that empower women to care for their children and choose life, the Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs falls considerably short of the ideal. Its reversal of Roe v. Wade presents an opportunity to protect unborn life, but if (as is likely) such state “protections” consist only of legal prohibitions on abortion without expansions in the social safety net, few unborn lives will be saved, and the lives of women facing crisis pregnancies will not be improved. But even if the political context surrounding Dobbs is not ideal, those who are consistently and genuinely pro-life can still seize this moment and save lives by working for policies that will empower women and offer positive alternatives to abortion.

Daniel K. Williams is a professor of history at the University of West Georgia and the author of several books on religion and American politics, including God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right and The Politics of the Cross: A Christian Alternative to Partisanship. He is a Contributing Editor at Current.

***

A reinvigoration of “the people”

As a mom and a scholar, I think a lot about civic formation: If we live in a nation “of, for, and by” the people, then for obvious reasons it matters what kind of people we are, and I strive in my public and private roles to help cultivate the virtues and knowledge necessary for wise citizenship. Along with an understanding of the principles of limited government, I hope to pass along an appreciation that such a government depends on the twin pillars of a robust sense of personal responsibility and profound care for the common good. Both of these virtues will be sorely needed in the wake of the Dobbs decision.

Dobbs is a scary decision for many, I think, because of the massive erosion of trust not just in political institutions but in the body politic itself over the past decades. We have become preconditioned to believe the worst of those whose political views differ from our own. We not only find it hard to believe that their policy positions are oriented towards the public good, we wonder if they might be bent on actively undermining it. Certainly we see this suspicion in the charged rhetoric (on all sides) around the question of abortion access. Such rhetoric has been encouraged in part because Americans have become accustomed to ceding the most essential political questions to unelected officials, thanks to the growth of judicial activism and the administrative state. When the “real” political work is being handled elsewhere, the average citizen need not make much of an effort towards civility or persuasion in relation to those with whom they disagree.

The Dobbs decision reverses a long-standing but bad precedent. We ought to applaud the Court for recognizing its previous error: Whatever one’s policy preferences, the fact is that Roe was a bad decision, one that substituted judicial will for genuine constitutional authority. This is not a particularly controversial statement: As Alito points out in the Dobbs opinion, commentators from both ends of the political spectrum and with widely varying policy preferences have been criticizing the reasoning in Roe since it was handed down. Casey did nothing to improve the situation. Dobbs, which returns the question of abortion’s legality and accessibility to the legislatures of the several states, returns also some significant measure of political responsibility to citizens who have grown unused to wielding it. In this sense, Dobbs presents an opportunity for a reinvigoration of “the people” as genuine participants in their own governance. This will not be a painless transition, but insofar as the best security for rights lies with individuals, it will be a hopeful one.

Sarah A. Morgan Smith is an independent scholar whose interests center around all the things you aren’t supposed to talk about in polite society: politics, religion, and the Yankees. After studying the history of political thought at Rutgers, she taught for several years before retiring to focus on the moral and civic formation of her own three children.

***

Will the victors be the spoiled?

Where will the opponents of Roe go from here? Perhaps they will go after each other.

One of my undergraduate teachers, the pro-life stalwart Hadley Arkes, is fond of quoting Abraham Lincoln’s rejoinder to Stephen Douglas in the sixth of their famous debates: No one can claim a “right to do wrong.”

Lincoln was objecting to Democrats who called slavery wrong but did not want to interfere with the autonomy of slaveholding states. He was also objecting to Douglas’s popular-sovereignty position—that the legality of slavery should be up to the citizens of individual states, as expressed through their elected representatives. The question of slavery, held Douglas, was a question for the states.

Lincoln argued that if you really believe slavery to be a moral wrong you cannot claim that anyone—any individual, state, or political body—has a “right” to enshrine that wrong in law.

The argument is beautiful and powerful. And today its central place in the thought of leading pro-life intellectuals like Arkes is important. That’s because for these pro-lifers, Dobbs v. Jackson must be a disappointing decision.

Throughout Dobbs, Justice Alito makes a Stephen Douglas-style argument, one that dodges questions about the morality of abortion and that puts popular sovereignty first. Consider these lines from the decision:

“Roe and Casey each struck a particular balance between the interests of a woman who wants an abortion and the interests of what they termed ‘potential life.’ . . . But the people of the various States may evaluate those interests differently.”

“Our decision returns the issue of abortion to those legislative bodies, and it allows women on both sides of the abortion issue to seek to affect the legislative process by influencing public opinion, lobbying legislators, voting, and running for office.”

“The authority to regulate abortion must be returned to the people and their representatives.”

The upshot: In returning abortion policy to the states Dobbs creates new room for controversy among the opponents of Roe.

Many opponents of Roe will be satisfied with the Court’s reasoning in Dobbs, content to live in a nation in which some states ban abortion and others do not. They will see this decision as a victory for popular sovereignty, for democratic self-government, and for states’ rights.

But a solid core of leading pro-lifers will see Dobbs as just a new kind of pro-choice decision, one that merely shifts a right to choose from individuals to state legislatures. They will see this decision as morally indefensible—as asserting a “right to do wrong”—and thus worth fighting, probably by pursuing a national ban on abortion. At least some of them, in doing this, will claim the mantle of Lincoln.

Will the opponents of Roe be able to sustain, post-Dobbs, the kind of political solidarity they maintained before it—especially given that a majority of Americans say abortion should be legal in all or most cases?

It seems unlikely—though, of course, many of us thought, in the not-so-distant past, that overturning Roe was unlikely.

Susan McWilliams Barndt is Professor of Politics at Pomona College in Claremont, California. She has authored and edited numerous books including A Political Companion to James Baldwin (2017) and The American Road Trip and American Political Thought (2018).

***

The Return of the Queen

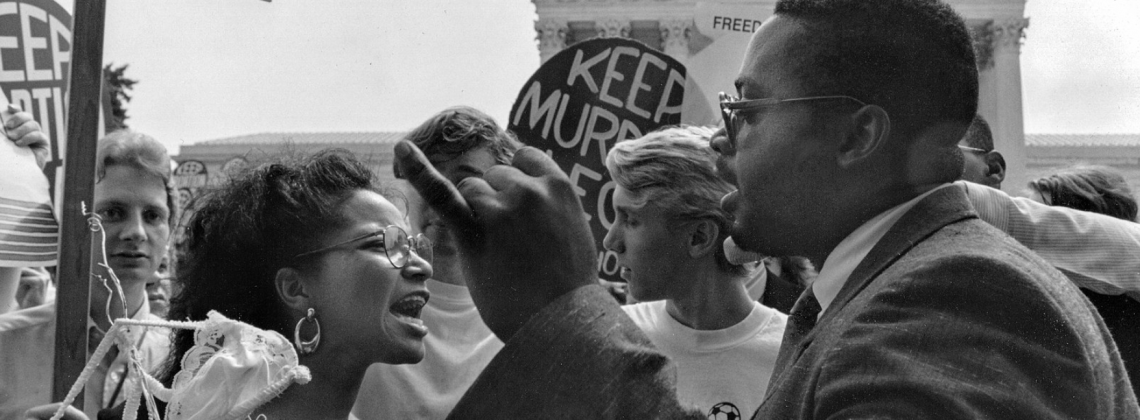

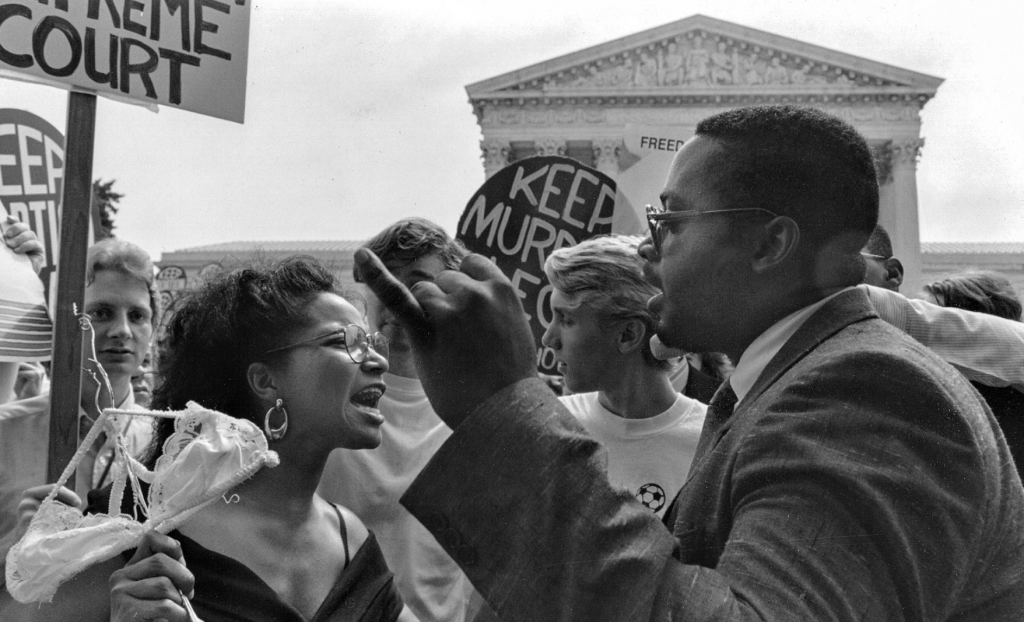

What follows riffs on The Boondocks episode “Return of the King,” when character Huey Freeman dreams Martin Luther King was shot but survives in a coma, waking thirty-two years later. Here’s my dream of what King would find if he awoke today:

The Equal Rights Amendment was ratified by all fifty U.S. states on December 25, 1972.

June 2022: the Supreme Court overturns Roe v Wade. News does not trend on Twitter. CNN and Fox News provide sixty seconds of coverage.

Evangelicals turn out to have been vital in ERA’s ratification. A multi-racial, multi-ethnic high school women’s coalition starts the “Second Greatest” movement, based on Jesus’ instruction that our second greatest command, after loving God, is “love your neighbor as yourself.” Millions of evangelicals join throngs who surround state legislatures, urging—demanding—the reversal of over a century of Christian support of women’s exploitation. The Second Greatest insists on: removing economic and political disparities; a minimum wage 25% higher for women; 3% maximum interest on home or business loans for women; providing recompense for generations of advantaging men while disadvantaging women.

In 1973, Roe v Wade’s legalization of abortion launches another Second Greatest wave. Evangelicals again march alongside millions, demanding laws enabling every woman to require state-funded paternity tests of any man; requiring full financial support of children by fathers or the state until twenty-one years old, including trust funds for college, real estate, and business start-ups; covering all adoption costs if a mother chooses not to raise a child and the father could, would, or should not. Every state passes these laws. When fringe “men’s rights” groups initiate #MeFirst legal challenges, evangelicals respond with #QueenEsther and non-evangelicals with #QueenRamonda, calling for society to treat all women like queens.

The five woman-four man Supreme Court votes 9-0, upholding the law’s constitutionality.

When Roe v Wade is reversed, the few abortions are usually only when the mother’s life is jeopardized. America has witnessed dramatic social, legal, economical, and political shifts. In a “woman on the street” interview, thirty-five-year-old Pennsylvanian Shannon Ruth Hancock Whitesell summarizes it well: “In a different reality, we’d be asking why it is that so many women don’t feel safe or secure bringing a child into the world with the man who fathered the child. At least I live in a world where we’ve made sure that few women must face that reality.” It’s not surprising, then, that few people pay much attention to a case that most Americans can’t even remember.

It hurts to dream.

Scott Hancock is Professor of History and Africana Studies at Gettysburg College. Prior to that he spent fourteen years working in group homes with teenagers in crisis. He is currently exploring how places like the Gettysburg battlefield can put African Americans and slavery back into the heart of the story told by national park landscapes and memorials.