How much will we sacrifice for the illusion of control?

Like many of us, I was still processing the racist murderous rampage in Buffalo when news of Uvalde broke. As a Connecticut resident during Sandy Hook, I felt for my Texan friends as they tried to wrap their minds around what had happened in their home state.

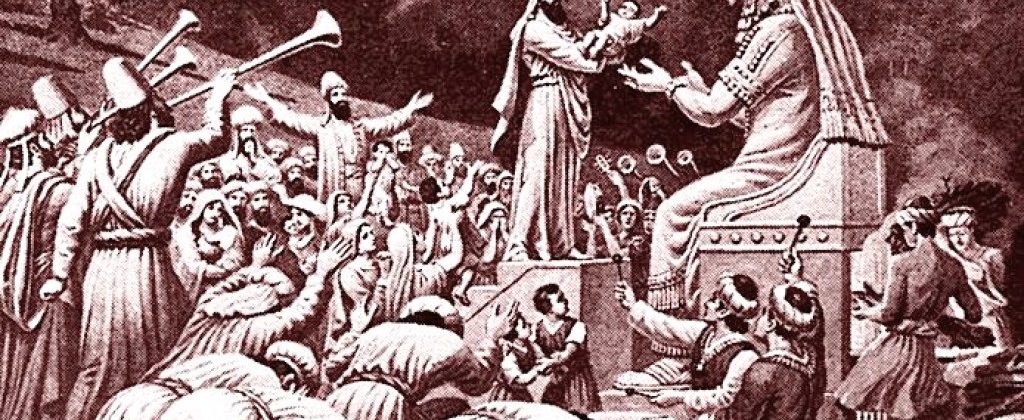

I have since been in conversation with a politically diverse group of people. Despite our differences we seem to agree that the shootings signal deep spiritual dysfunction in American society. Why has such carnage become commonplace? And why do we lack the collective will to confront it? This got me thinking about the cult of Molech, which crops up repeatedly in the Hebrew Bible. As repugnant as its rituals were, it remained alluring for reasons that shed light on our own cultural context.

Although the first of the Ten Commandments prohibits worship of other gods, the people of Israel didn’t become monotheists overnight. Even after King Solomon built the first temple to the God of Israel shrines to other gods abounded. One such deity was Molech: a fertility god who demanded child sacrifice.

In hindsight we can appreciate how painfully at odds the Molech cult was with the worship of the God of Israel. But this incongruity wasn’t so clear at the time. Molech shrines were located at the base of the Temple Mount, the center of Jewish worship. The prophet Ezekiel expressed dismay at people performing child sacrifice and going to temple on the same day (Eze. 23:32-39). Where prophets saw flagrant idolatry, however, Molech worshipers saw complementarity.

Preserving Molech shrines in such a public place required the patronage of the powerful. In Israel this came from figures like King Solomon, who sanctioned the cult of Molech after overseeing the construction of the Israelites’ first temple to the God of Israel (I Kings 11:5-7), or King Ahaz, who sacrificed his own son (2 Kings 16: 3-4). The Bible condemns their actions. But how would Molech worshipers perceive them? Probably as willing to pay the price necessary to ensure divine favor.

The cult of Molech was based on a grotesque understanding of the divine. The Hebrew Bible establishes as much in the foundational story of God testing Abraham’s faith by commanding him to sacrifice his son Isaac (Gen. 22:1-19). Once Abraham proved his unwavering loyalty, God spared Isaac’s life precisely because God would never require human sacrifice. Yet Molech-worship persisted in Israel for centuries. Why?

Its persistence boils down to human psychology. In the face of life’s inherent risk and uncertainty we crave a sense of control. True religion, however, reminds us that our fate is in God’s hands. Relinquishing control frees us to focus on loving God and neighbor, enabling us to move through a broken world in a God-honoring way. As the Psalmist put it: “Some trust in chariots, and some in horses, but we trust in the name of the Lord our God” (Ps. 20:7). But our desire for control constantly undermines this trust. We are so desperate to feel a sense of agency over life’s chaos that we will sacrifice what is most precious to us to get it. It is precisely this impulse that drove the cult of Molech. In exchange for child sacrifice Molech promised fertility—large families, prolific herds, abundant crops—and safety. Molech, in other words, offered the sense of agency that the God of Israel required worshipers to surrender. God required radical trust; Molech required blood sacrifice. The desire for control ran so deep that people would sacrifice their own children to get it—while still professing loyalty to the God of Israel.

The sense of control Molech offered was illusory yet deeply alluring. With each sacrifice, Molech worshipers doubled down on a contradiction: They could both serve the God of Israel and control life’s chaos. They eventually lost the ability to distinguish between idolatry and true worship.

A similar pattern is playing out in contemporary America. Precisely because our nation has enjoyed such overwhelming prosperity we are especially vulnerable to the illusion of control—that we are capable of mastering fate by ensuring our own flourishing and safety. The astonishing lengths we go to perpetuate this illusion reveals itself in our toxic relationship to guns. Our gun culture exposes our Molech problem.

In stating this I refer neither to hunting rifles, which serve a clear practical purpose, nor to responsible handgun ownership, but rather to the assault rifle. It is the modern equivalent of the horse and chariot: a specialized tool of war, subjugation, and terror. No matter what a person professes to believe, to own a weapon engineered for mass murder is to place one’s trust in horses and chariots rather than God. Our misplaced trust has spawned an all-American death cult. As a society we would rather tolerate massacres at elementary schools and supermarkets and concerts and clubs and hospitals than restrict access to AR-15s. Like devotees of the cult of Molech we have determined that some of us will have to be sacrificed to secure safety and prosperity for the rest of us. And if the cult of the gun demands children, so be it.

Regardless of what special interest groups or talking heads claim, owning an assault weapon is not about individual freedom or the Second Amendment. It is about an intoxicating sense of control. It gives us the ability not merely to protect ourselves and our families but to obliterate perceived enemies by the dozen. This makes us feel as if we could hold fate itself hostage: With such awesome power to take scores of human lives nestled in the palm of one’s hand, who needs trust in God?

Some of the loudest defenders of our gun culture are correspondingly loud about their faith. Such figures are the modern-day equivalents of Solomon and Ahaz. You can’t brandish AR-15s and profess trust in God any more than you can sacrifice to Molech and worship on the Temple mount.

Our moment of reckoning is upon us. For America to begin to heal spiritually, it must abandon its hand-held, high-capacity altars to Molech.

Jeremy Sabella lectures at Dartmouth College and is the author of An American Conscience: The Reinhold Niebuhr Story.