“He best expressed his preference for his wild homestead by saying that his Bible seemed truer to him there.”

In Book Marks, an occasional feature at Current, we take fresh cuttings from old books. Why look at old books? Because there’s a slat loose in the fence they’ve got us penned up in, and if we jiggle it free, we’ll see better what’s going on out there.

I offer an opening comment for orientation, but that’s not where the action is. I hope the words of those who have gone before will speak.

*

It’s a big world, and now that the horseless carriage and the aeroplane have had their way with us, we know hardly any of it. One of the frontiers worth crossing as often as you can when reading is the watershed between us and books from a world where people still went on foot or hoof from place to place (and usually didn’t go anywhere very far at all). Not to romanticize insularity—but there’s a difference between provincialism and localism.

In this passage from the lucid typewriter of Nebraska’s Willa Cather, we meet an immigrant who “keeps his place” both on the land and in the book he’s reading. And it turns out that the text and the field aren’t unconnected. His thickheaded neighbors have labeled him “Crazy Ivar,” uncomprehending of his neurodiversity, but I’m pretty sure he was on to something.

One New York critic dismissed Cather’s 1913 novel O Pioneers!, saying, “I simply don’t care a damn what happens in Nebraska” (“About This Edition” [Doubleday, 1999], p. xl). Don’t make his mistake.

Hear what she has to say:

“Look, look, Emil, there’s Ivar’s big pond!” Alexandra pointed to a shining sheet of water that lay at the bottom of a shallow draw. At one end of the pond was an earthen dam, planted with green willow bushes, and above it a door and a single window were set into the hillside. You would not have seen them at all but for the reflection of the sunlight upon the four panes of window-glass. And that was all you saw. Not a shed, not a corral, not a well, not even a path broken in the curly grass. But for the piece of rusty stovepipe sticking up through the sod, you could have walked over the roof of Ivar’s dwelling without dreaming that you were near a human habitation. Ivar had lived for three years in the clay bank, without defiling the face of nature any more than the coyote that had lived there before him had done.

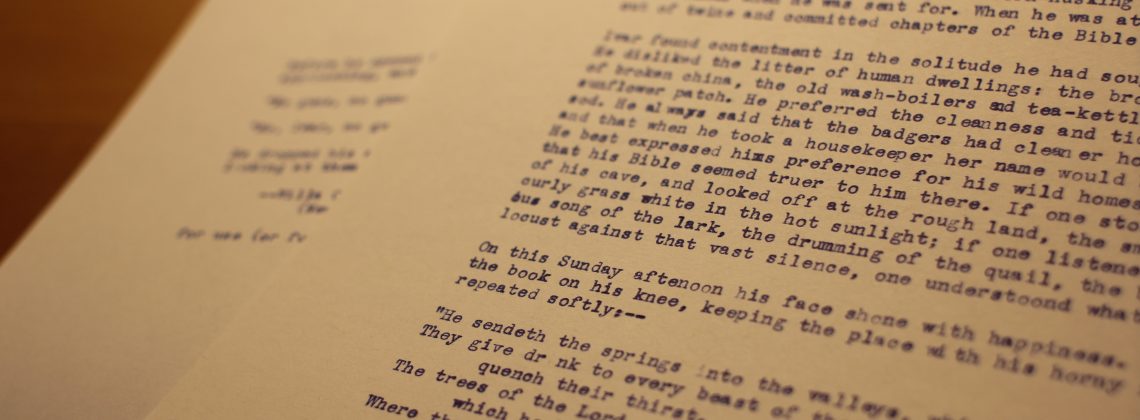

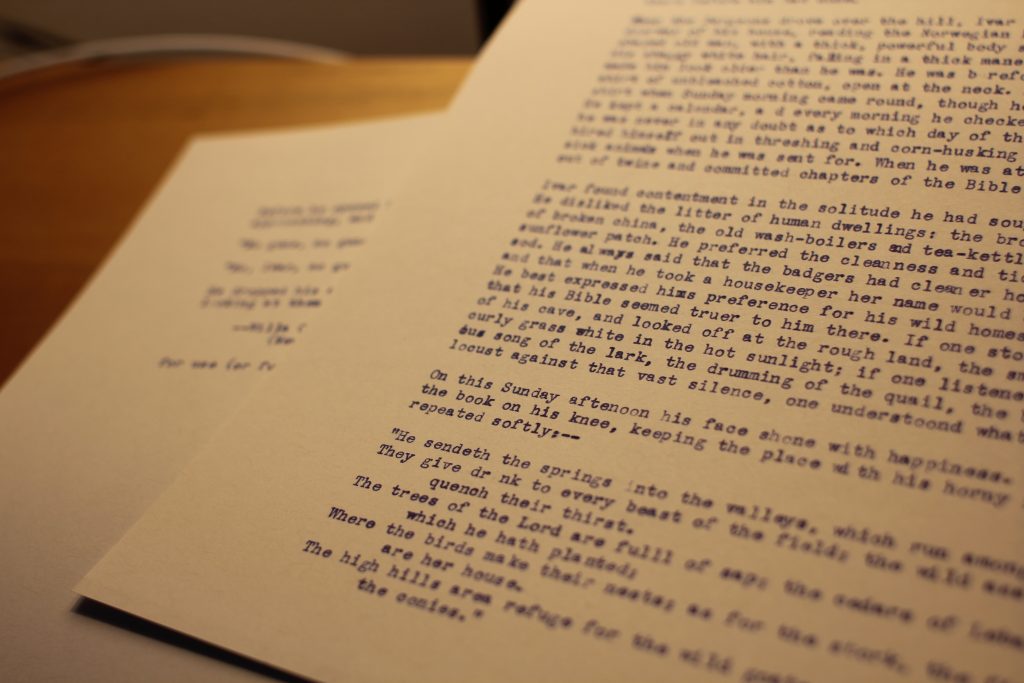

When the Bergsons drove over the hill, Ivar was sitting in the doorway of his house, reading the Norwegian Bible. He was a queerly shaped old man, with a thick, powerful body set on short bow-legs. His shaggy white hair, falling in a thick mane about his ruddy cheeks, made him look older than he was. He was barefoot, but he wore a clean shirt of unbleached cotton, open at the neck. He always put on a clean shirt when Sunday morning came round, though he never went to church. He kept a calendar, and every morning he checked off a day, so that he was never in any doubt as to which day of the week it was. Ivar hired himself out in threshing and corn-husking time, and he doctored sick animals when he was sent for. When he was at home, he made hammocks out of twine and committed chapters of the Bible to memory.

Ivar found contentment in the solitude he had sought out for himself. He disliked the litter of human dwellings: the broken food, the bits of broken china, the old wash-boilers and tea-kettles thrown into the sunflower patch. He preferred the cleanness and tidiness of the wild sod. He always said that the badgers had cleaner houses than people, and that when he took a housekeeper her name would be Mrs. Badger. He best expressed his preference for his wild homestead by saying that his Bible seemed truer to him there. If one stood in the doorway of his cave, and looked off at the rough land, the smiling sky, the curly grass white in the hot sunlight; if one listened to the rapturous song of the lark, the drumming of the quail, the burr of the locust against that vast silence, one understood what Ivar meant.

On this Sunday afternoon his face shone with happiness. He closed the book on his knee, keeping the place with his horny finger, and repeated softly:—

“He sendeth the springs into the valleys, which run among the hills;

They give drink to every beast of the field; the wild asses quench their thirst.

The trees of the Lord are full of sap; the cedars of Lebanon which he hath planted;

Where the birds make their nests: as for the stork, the fir trees are her house.

The high hills are a refuge for the wild goats; and the rocks for the conies.”

Before he opened his Bible again, Ivar heard the Bergsons’ wagon approaching, and he sprang up and ran toward it.

“No guns, no guns!” he shouted, waving his arms distractedly.

“No, Ivar, no guns,” Alexandra called reassuringly.

He dropped his arms and went up to the wagon, smiling amiably and looking at them out of his pale blue eyes.

— Willa Cather, O Pioneers! (1913; repr. New York Public Library Collector’s Edition, New York: Doubleday, 1999), 82–83.

*

Jon Boyd is keeper of Book Marks at Current. He is associate publisher and academic editorial director at InterVarsity Press, the saxophonist in an improvisational rock band, a user of manual typewriters, and (with his wife and daughters) a resident of the City of Chicago.

As much as I like Cather, she sometimes goes a little soft. One of the refreshing things about Paramount+’s *1883* is it has enough bite to sometimes be the anti-Cather, as when Elsa offers her meditation on the west:

“I had convinced myself of the world’s ambivalence towards its inhabitants. Until I came to this place. This place doesn’t want inhabitants at all. Every plant is inedible. Every creek bed is dry. Though only September, snow covers the mountain peaks. Winter can’t wait to have at us. Can’t wait to join with the land and run us off or kill us. If land can have emotions, this land hates. It hates us. And everyone can feel it.”

Is 1883 a movie about Cather?

No. TV series about the west.

https://chicago.suntimes.com/movies-and-tv/2021/12/19/22839771/1883-review-paramount-yellowstone-prequel-series-tim-mcgraw-faith-hill