The new understanding of “legitimate political discourse” was a long time in the making

How did the party of Abraham Lincoln, Calvin Coolidge, and Dwight Eisenhower become the party of political insurrection? When the Republican National Committee called the January 6th attack on the US Capitol “legitimate political discourse,” one might be forgiven for wondering how a party of the establishment that was once the paragon of stability and restraint became a haven for revolutionaries.

Did this start with the election of Donald Trump? With the creation of the Tea Party? Or did it begin instead with much earlier historical developments, with each choice the party made propelling it closer to a moment where it would lose all touch with its establishment roots?

The long road to the GOP’s changed identity may have begun ninety years ago, in the midst of the Great Depression, though at that time no one realized what was happening. For more than half a century before the 1930s the GOP was the establishment party in every sense of the term. The wealthiest and most educated regions of the country were Republican, as were the majority of voters. Republicans controlled the White House for forty-six out of the sixty-four years between 1869 and 1933. During that time there were eleven Republican presidents and only two Democratic.

Because they were the governing establishment, Republicans were not opposed to the growth of the federal government. On the contrary, many of the nation’s progressives were Republicans, just as the defenders of business interests were. There was room for both in the party because each group represented different wings of an establishment that was comfortable with existing institutions, whether associated with the government or private corporations.

But the Great Depression changed Republicans’ relationship with the governing establishment. A majority of Americans blamed President Herbert Hoover for the crisis and voted him and his fellow Republicans out of office. With the exception of Dwight Eisenhower’s presidency, Republicans would not control the executive branch for the next thirty-six years, and they would rarely control the legislative branch either. As an opposition party, they positioned themselves as critics of the new governmental establishment: the New Deal order. Republicans disagreed among themselves about how hard to push back against the New Deal, with many liberals in the party still reluctant to oppose the growth of popular social programs. But although the party would retain a progressive wing for several more decades, its identity began to change into a party of private market solutions and public criticism of the welfare state. It was still an establishment party. But the establishment it represented increasingly came to be associated only with private industry, not the state.

As a party of business, the party was generally hostile toward labor unions, attracting a new generation of libertarian-minded entrepreneurs. Among them was Phoenix department store owner Barry Goldwater. Goldwater believed in protecting private property and limiting government interference in business—which is why he voted against the Civil Rights Act of 1964. That vote ensured him the support not only of southwestern conservatives but also white southern segregationists. Goldwater carried five states of the Deep South—a feat no Republican had achieved before. Unfortunately for him, he lost forty-four other states in the rest of the country.

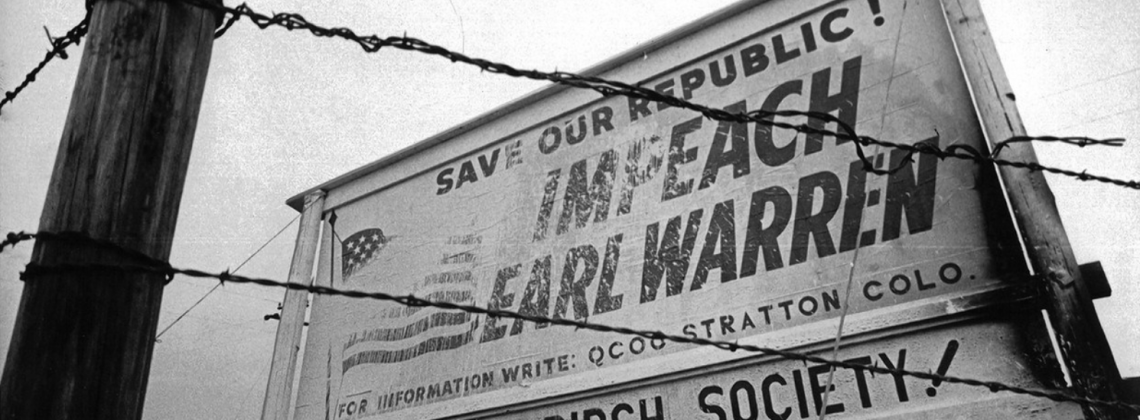

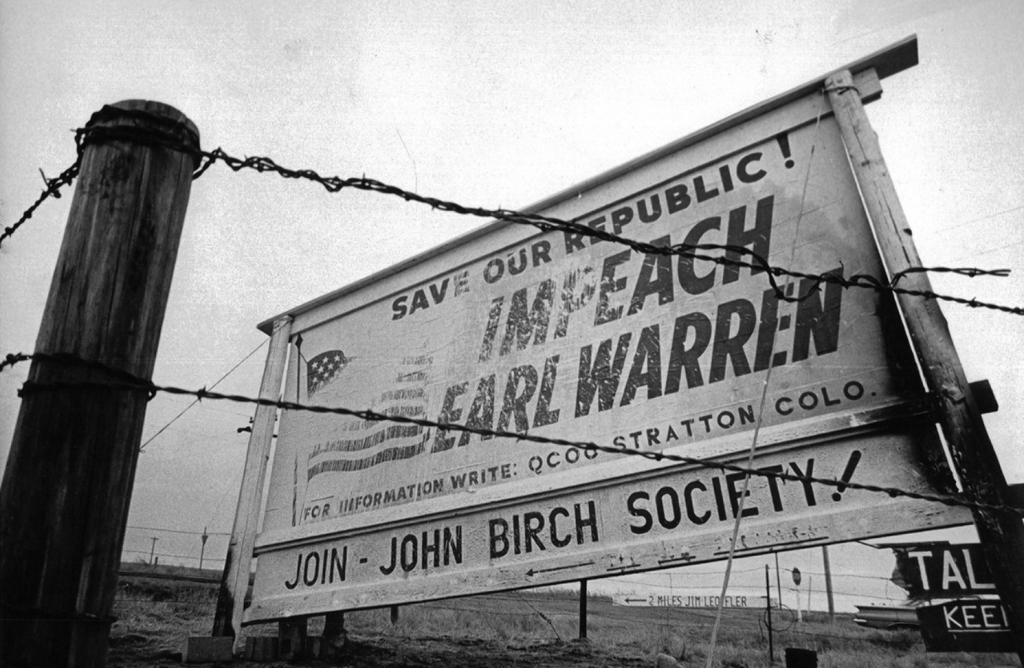

It was clear to many Republican Party leaders that Goldwater had driven the party off a cliff, and that he had turned the establishment party into a haven for libertarians, extreme anti-Communist conspiracy theorists, and above all, southern segregationists. Reclaiming the party for the establishment became their top priority. But putting the genie back in the bottle was not as easy as they had expected, now that the party’s center of gravity was moving to the South and West, where hostility to the federal government was much stronger than in the Northeast or Midwest. From 1964 through 1980 centrist Republicans from the North (who tended to be deficit hawks rather than tax-cutters) struggled with the “New Right” faction of the Republican Party that was emerging in the Sunbelt. The Sunbelt faction of the party won with Reagan’s election in 1980.

As George H. W. Bush discovered to his chagrin, no Republican president after the 1980s could get away with raising taxes to reduce budget deficits. A previous generation of Republicans had thought of themselves as prudently conservative caretakers of the federal government, but a new generation of Sunbelt conservatives wanted to take an axe not only to the deficit but to most of the social welfare state, including, by the early 21st century, Social Security.

For most of the late 20th century, the GOP marketed its critique of government to white suburban families who were skeptical of government welfare programs for the poor but who wanted the federal government to enforce educational standards or provide loans to small businesses and college scholarships to their kids. When the suburban wing of the GOP controlled the party—as was the case in 1972—Republicans endorsed restrictions on handguns. But as the party became increasingly rural, southern, and western, any form of gun control became anathema. Northern Republican moderates became increasingly unhappy in a GOP that they no longer controlled, and they left the party at the beginning of the 21st century, ceding greater control to voters in the South and West who had a more negative attitude toward the federal government. As the Democratic Party remade itself into a moderate party of the establishment (as occurred during Bill Clinton’s presidency), the GOP in turn picked up the votes of people angry with the establishment.

By the time Donald Trump pledged to “drain the swamp,” there was already a large-scale Tea Party movement of angry voters within the Republican Party whose attitude toward Washington politicians was not much different from that of some of the Populists of the 1890s who had pledged to take a pitchfork to the president and poke him in his ribs. A short time earlier, no one would have suspected that there would be room in the Republican Party for a new generation of angry populists, but with the departure of the northeastern wing of the party and with the escalation in anti-government rhetoric, the party shifted from merely wanting to cut social programs to wanting a more radical overhaul of the entire system.

But even all of the Republican Party’s anti-government rhetoric did not quite prepare party leaders for an attack on the US Capitol—which is why their first response to the attack was to condemn it. Yet as it became apparent that Trump had no intention of backing down from his endorsement of the insurrectionists—and as it became clear that a sizeable contingent of the party’s new base of anti-government populists followed him in this stance—many congressional Republicans decided that they, too, had to approve a violent attack on their own institution if they wanted to retain the support of the voting base they had created.

It was a long road from skepticism about the New Deal to support for an insurrection, and there were many points along the way at which Republicans could have changed course and refused to embrace the extreme anti-government rhetoric that led the party from cautious conservatism to revolutionary anarchy. It may not be too late to turn back. The party could repudiate the insurrectionists and reclaim the mantle of a more responsible conservatism if it wanted to—but doing so would risk the wrath of the voters on which the party depends, now that its original base of Wall Street investors and middle-class northeasterners has started to leave the GOP. At this point, party leaders will have to ask themselves which is more important: preserving the party’s historic values and the nation’s democracy? Or winning the next election?

Daniel K. Williams is a professor of history at the University of West Georgia and the author of several books on religion and American politics, including God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right and The Politics of the Cross: A Christian Alternative to Partisanship.

This is a good summary of the political changes but omits mention of the growth of neoliberalism since the 1970s, a development that has accelerated income and educational inequalities and flattened working class incomes. When working class and small business Americans have had no real increase in earnings in forty years, one understands their skepticism of a financially-driven establishment which has experienced the opposite. Our economy has de-industrialized and globalized, shipping countless jobs to cheaper locales overseas; unions have been decimated; health care is increasingly unaffordable; and college costs have exploded. The bottom fifty percent of the country has been impoverished for the benefit of the top twenty percent. That explains why Trump and his ilk are able to articulate a politics of resentment and mobilize millions of angry voters.