Long Live Death on the Nile—and Agatha Christie

The greatest mystery of Agatha Christie’s novels is why we keep returning to them. It’s not, it goes without saying, that the stories aren’t any good. The mystery rather is why our insatiable interest continues when the primary pleasure of the stories is completely dependent on not knowing the ending. The phrase “no spoilers” might have been invented for Christie. Her play “The Mousetrap” had the longest run in the history of London’s West End. It opened in 1952 and was only shut down by the pandemic in 2020. Audiences were always cautioned not to give away the ending.

Dame Agatha Christie was the grand mistress of misdirection. What she gave with one hand in terms of the ingenuity of her plotting she often took away with the other in the flatness of her characterization. She was the champion at playing this clever game, but its rules meant that readers could not really know the inner lives of her characters. Everyone must be a suspect and therefore anyone might morph into most anything in the final chapter—that sweet nurse has actually been nursing a grudge, that loyal cook is really a long-lost cousin who has been cooking up a plan to inherit the family fortune.

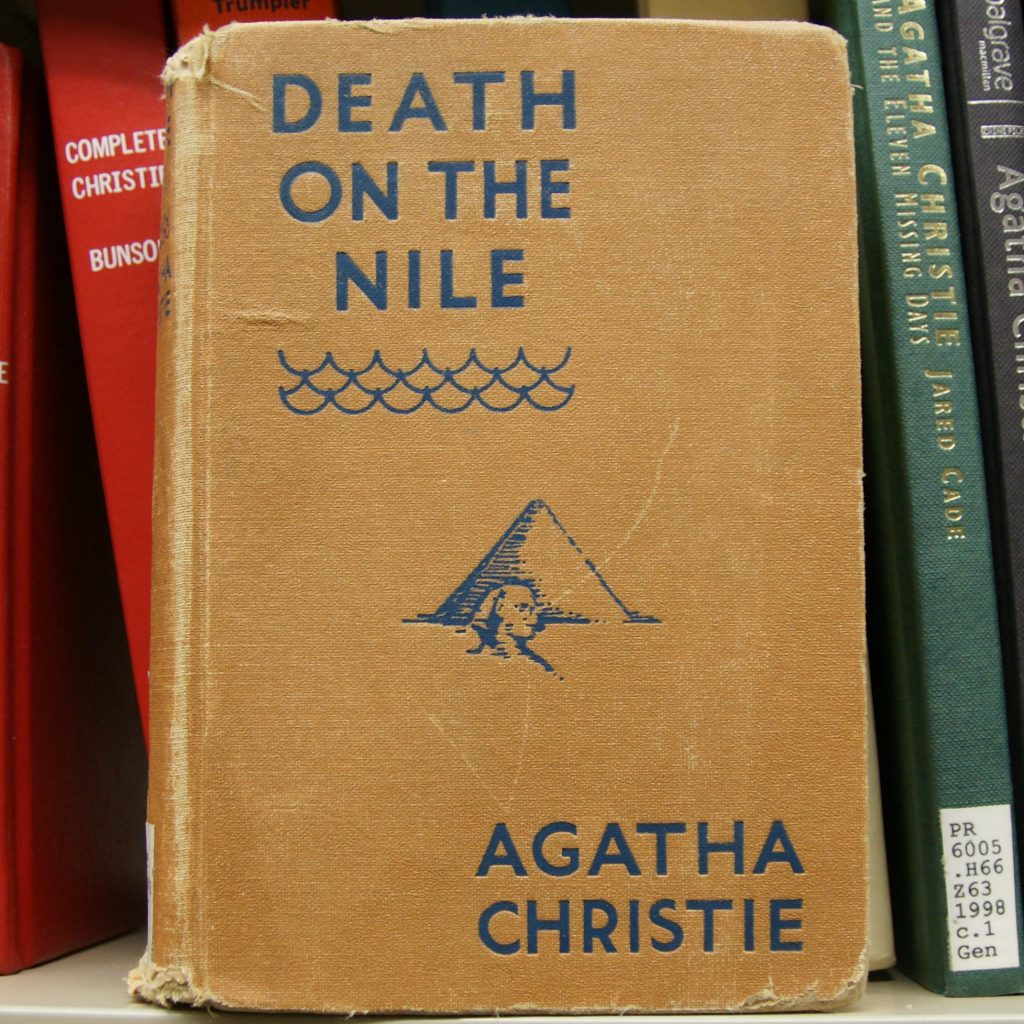

It would seem, in short, that returning to a Christie story would be like re-doing the same crossword puzzle. Yet here we go again. Death on the Nile has just been released as a feature film directed by Kenneth Branagh. The book was published in 1937. It became a play in the 1940s and was first televised in 1950. In 1978 it became an acclaimed film exploding with stars (including Maggie Smith, Peter Ustinov, David Niven, and Bette Davis). It was filmed again in 2004 as part of the Agatha Christie’s Poirot series, meaning that viewers now have three satisfying versions to choose from.

By way of contrast, there are Shakespeare plays that have never been made into a feature film. What is the solution to this final Christie puzzle of her enduring appeal? I think the key lies in the fact that she created two characters people have come to know and love: Jane Marple and Hercule Poirot. Readers could trust that these two would not suddenly be revealed to be some person other than the one who had won their affection. They are, above all else, endearing.

I have often wished that there were more Marple books. It was a triumphant day in my life when I learned to think of my English mother-in-law as Miss Marple. She too is highly intelligent and shrewd, but she comes off as talking aimlessly due to a habit of delivering a torrent of seemingly pointless information before making the connection whereby it gains its import. Christie, however, realized that it would strain probability for an elderly spinster living in a quiet village to rack up too high a body count, and therefore did not return to the sage of St Mary Mead very often. We can at least be grateful that Miss Marple was well supplied with nephews and nieces who could stumble upon intrigue. Poirot, by contrast, was the world’s greatest detective and therefore trouble could always come to find him.

It would not be quite true to say that Kenneth Branagh has played every great British literary character from Hamlet to Harry Potter. After all, he was over forty by the time that Potter’s first year of school made it to the screen. Still, Branagh managed to get in on the act for the second film with a pleasing turn as Gilderoy Lockhart. And he did direct and star in a celebrated version of Hamlet (1996). Now he is determined to create a canonical depiction of Hercule Poirot, an ambition begun with Murder on the Orient Express (2017).

Poirot endears himself to readers through a cluster of overlapping traits: his meticulousness, his vanity, his boastfulness, his irritation at slackness, his preoccupation with being immaculate. Branagh is true to the cozy tradition of the Golden Age of British detective fiction. Nevertheless, his depiction of Poirot is a couple shades darker. He leans, for instance, into the deduction that Poirot’s apparent fuzziness is actually a manifestation of obsessive-compulsive disorder. The Belgian detective doesn’t merely prefer symmetry because he is an aesthete. Being brought an uneven number of dishes can become a disturbance that agitates his mind until it is resolved.

Conan Doyle discovered that Sherlock Holmes was too popular to be killed off. Similarly, Christie learned that Poirot was too popular to begin his fictional life as an elderly man pursuing detection in his retirement. Branagh resets the chronology aright: He has Poirot serving as a young soldier in the First World War. This backstory also provides an opportunity to deepen Poirot’s character into that of a wounded soul. As a suspect observes, “He’s lonely for a reason.”

Branagh’s Death on the Nile is immensely enjoyable, even for someone like me who already had the plot down cold. There are welcome winks for the hardcore fans. One is regarding the artificial way so many Christie novels end with the detective seemingly making the case, each in turn, that every character is the perpetrator. In Branagh’s version, a friend gives an eye-roll warning: “He accuses everyone of murder.” The knowing reply: “It is a problem, I admit.”

At the start of the film, we see Poirot contemplating the Sphinx, that great unsolved riddle of ancient civilization. Later, he is holding a copy of Edwin Drood, a murder mystery that readers need to solve for themselves, as its author, Charles Dickens, died before it was finished it. Branagh is apparently planning to adapt more Christie novels for the big screen. Together we can continue to puzzle out the unsolved mystery of why Hercule Poirot was the man he was.

Timothy Larsen teaches at Wheaton College and is an Honorary Fellow at Edinburgh University. He is the author of John Stuart Mill: A Secular Life and the editor of The Oxford Handbook of Christmas.

I never get enough of Death on the Nile. Somehow I forget the ending while reading or watching it. Enjoyed your article.

Thanks, Susan! Yes, there are lots of mysteries that I re-visit and I think in the middle, “Do I remember that person being the murderer or do I just remember having a theory that that person was the murderer that later proved false?”